By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

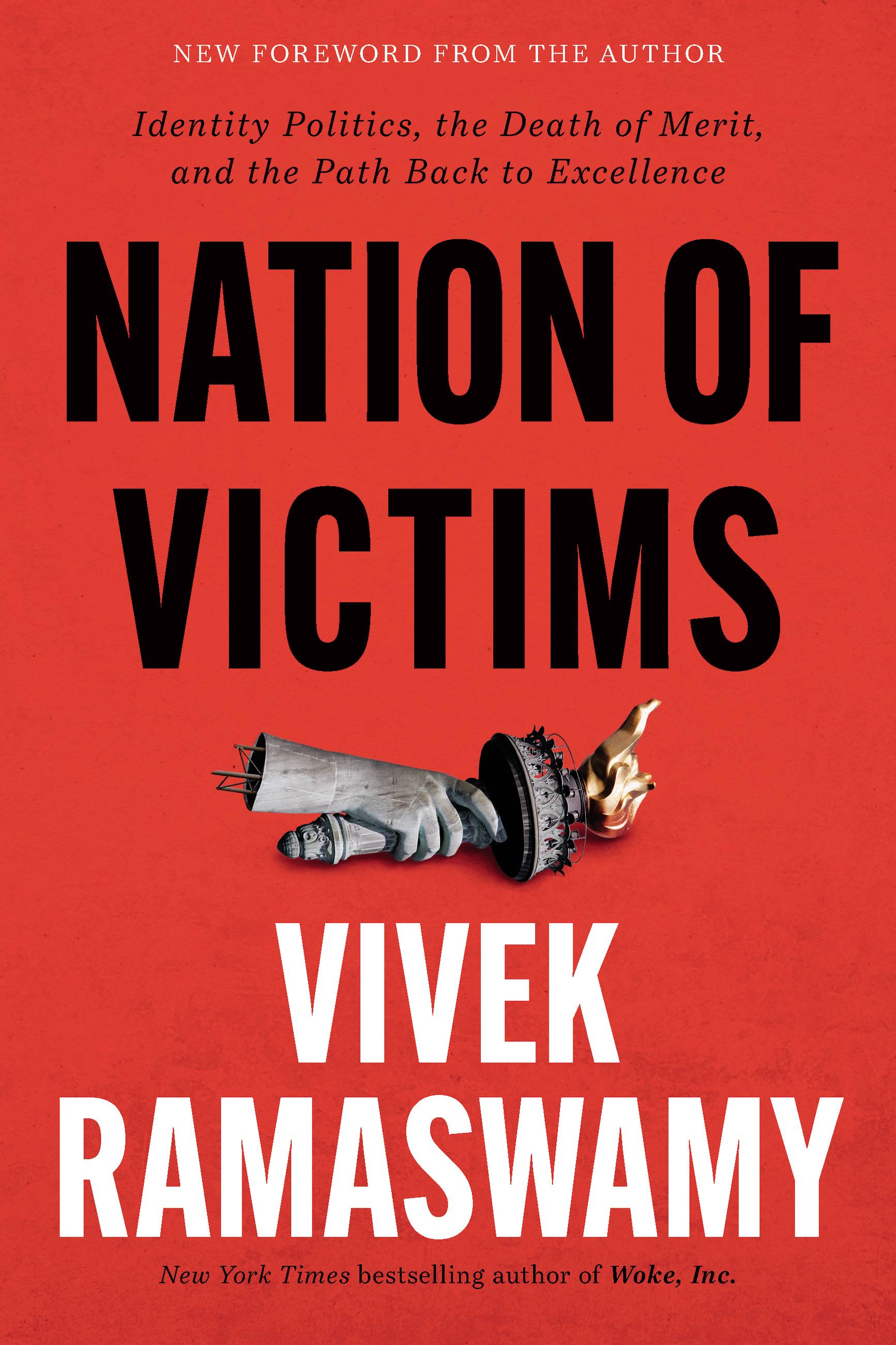

Nation of Victims

Identity Politics, the Death of Merit, and the Path Back to Excellence

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 12, 2023

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546002970

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 12, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

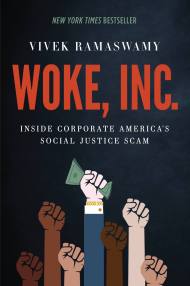

The New York Times bestselling author of Woke Inc. and a 2024 presidential candidate makes the case that the essence of true American identity is to pursue excellence unapologetically and reject victimhood culture.

Hardship is now equated with victimhood. Outward displays of vulnerability in defeat are celebrated over winning unabashedly. The pursuit of excellence and exceptionalism are at the heart of American identity, and the disappearance of these ideals in our country leaves a deep moral and cultural vacuum in its wake. But the solution isn’t to simply complain about it. It’s to revive a new cultural movement in America that puts excellence first again.Leaders have called Ramaswamy “the most compelling conservative voice in the country” and “one of the towering intellects in America,” and this book reveals why: he spares neither left nor right in this scathing indictment of the victimhood culture at the heart of America’s national decline. In this national bestseller, Ramaswamy explains that we’re a nation of victims now. It’s one of the few things we still have left in common—across black victims, white victims, liberal victims, and conservative victims. Victims of each other, and ultimately, of ourselves.

This fearless, provocative book is for readers who dare to look in the mirror and question their most sacred assumptions about who we are and how we got here. Intricately tracing history from the fall of Rome to the rise of America, weaving Western philosophy with Eastern theology in ways that moved Jefferson and Adams centuries ago, this book describes the rise and the fall of the American experiment itself—and hopefully its reincarnation.

Now updated with a new foreword from the author.

-

“Vivek Ramaswamy’s first book solved one of the strangest riddles of our time: how corporate America went woke. His new book addresses an even bigger question: how a nation that once celebrated heroism turned into a nation that celebrates victimhood. Compelling, persuasive, and deeply needed.”Douglas Murray, Bestselling author and associate editor of The Spectator

-

“This book shows why Vivek Ramaswamy is one of the most original thinkers—and doers—of our time. Instead of wallowing in the left’s cult of victimhood and its recipe for mediocrity, Vivek challenges all of us to return to the path of achievement and excellence.”Ben Shapiro, Bestselling author and host of The Ben Shapiro Show

-

“If you want an intellectually honest book that spares no side from their hypocrisies, Vivek Ramaswamy’s NATION OF VICTIMS is it. He delivers thought-provoking anecdotes about the foundation of our country and what has shaped his independent worldview in a way that encourages substantive dialogue, understanding, and respect.”Tulsi Gabbard, Former congresswoman and Democratic candidate for president in 2020

-

“Vivek Ramaswamy presents a challenging alternative to a nation caught in a maelstrom of victimhood, calling on Americans to embrace the challenge of excellence instead. Along the way, he wrestles with the very real challenges of history as he slays the arguments of the woke. NATION OF VICTIMS takes on the strongest version of the modern left’s argument about who we are, and wins.”Ben Domenech, Editor at large of The Spectator

-

“Life is difficult; often, tragically so, rife with suffering and betrayal. Thus, the temptations of victimhood eternally beckon. Why not adopt that identity, and reap the benefits that hypothetically follow? Because doing so makes everything worse, including the suffering that justified the decision in the first place. As Vivek Ramaswamy takes pains to explain in his new, necessary, and salutary book, NATION OF VICTIMS.”Jordan Peterson, Bestselling author and host of The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast

-

“America should be a nation of underdogs striving for excellence, not a nation of victims embracing mediocrity—the thesis of Vivek Ramaswamy’s latest brilliant book. Brave and bracing with a panoramic historical sweep, NATION OF VICTIMS is impossible to put down.”Amy Chua, Yale Law professor and bestselling author