By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

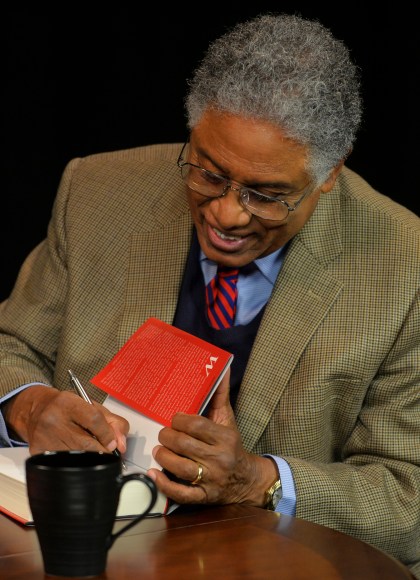

Knowledge And Decisions

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 1996

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465037384

Price

$31.99Price

$39.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $31.99 $39.99 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 1996. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

With a new preface by the author, this reissue of Thomas Sowell’s classic study of decision making updates his seminal work in the context of The Vision of the Annointed, Sowell, one of America’s most celebrated public intellectuals, describes in concrete detail how knowledge is shared and disseminated throughout modern society. He warns that society suffers from an ever-widening gap between firsthand knowledge and decision making—a gap that threatens not only our economic and political efficiency, but our very freedom because actual knowledge gets replaced by assumptions based on an abstract and elitist social vision f what ought to be.Knowledge and Decisions, a winner of the 1980 Law and Economics Center Prize, was heralded as a ”landmark work” and selected for this prize ”because of its cogent contribution to our understanding of the differences between the market process and the process of government.” In announcing the award, the center acclaimed Sowell, whose ”contribution to our understanding of the process of regulation alone would make the book important, but in reemphasizing the diversity and efficiency that the market makes possible, [his] work goes deeper and becomes even more significant.”

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group's Privacy Policy and Terms of Use