By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Charter Schools and Their Enemies

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541675148

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

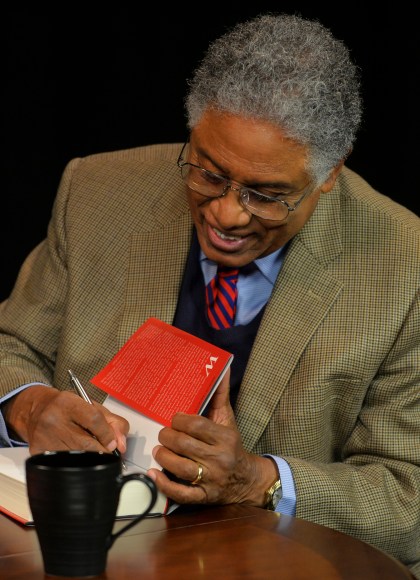

A leading conservative intellectual defends charter schools against the teachers' unions, politicians, and liberal educators who threaten to dismantle their success.

-

"A methodologically rigorous, closely argued, data-driven case for charter schools...Thomas Sowell is a national treasure in a nation that does not entirely deserve him."National Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use