By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

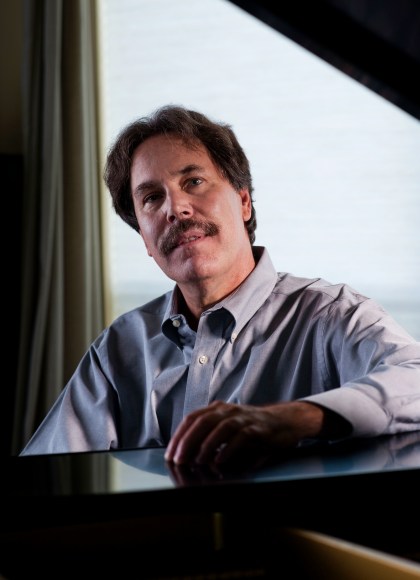

How to Listen to Jazz

Contributors

By Ted Gioia

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 17, 2016

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465097777

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 17, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In How to Listen to Jazz, award-winning music scholar Ted Gioia presents a lively introduction to one of America's premier art forms. He tells us what to listen for in a performance and includes a guide to today's leading jazz musicians. From Louis Armstrong's innovative sounds to the jazz-rock fusion of Miles Davis, Gioia covers the music's history and reveals the building blocks of improvisation. A true love letter to jazz by a foremost expert, How to Listen to Jazz is a must-read for anyone who's ever wanted to understand and better appreciate America's greatest contribution to music.

Genre:

-

"How to Listen to Jazz is an effort to teach casual listeners how 'careful listening can demystify virtually all of the intricacies and marvels of jazz.'"New York Times

-

"How to Listen to Jazz fills an important and obvious gap by offering a sensible and jargon-free introduction to what Gioia calls 'the most joyous sound invented during the entire course of twentieth-century music.' The book deserves a place alongside such classic works of jazz criticism as Martin Williams's The Jazz Tradition, Will Friedwald's Jazz Singing, the books of Gary Giddins and Gioia's own The History of Jazz."Washington Post

-

"[How to Listen to Jazz is a] satisfying new book.... One of the best features of the book is a set of 'music maps,' as Mr. Gioia calls them, that serve as a guide to individual recordings."Wall Street Journal

-

“Mr. Gioia could not have done a better job. Through him, jazz might even find new devotees.”Economist

-

"How to Listen to Jazz is a packed and useful introduction to the medium with suggestions and aids for the listener who wants to gain entrance to a rich and complicated body of work."Weekly Standard

-

“Amid the cacophony of the past year, one paean to improvised order emerged from the pen of music critic Ted Gioia. That book, How to Listen to Jazz, deserves your undivided engagement.”Brock Dahl, Washington Free Beacon

-

"How to Listen to Jazz is a thorough, impassioned guide to a sound that tends either to inspire deep, almost religious devotion or cause eyes to go crossed...[Gioia] elucidates the music in a way that increases the listener's sense of awe and wonder, rather than supplants it."Columbia Daily Tribune

-

"Gioia's engaging yet authoritative style makes How to Listen to Jazz not just a valuable primer but a delight to read."City Journal

-

A perfect way...to begin an understanding of a music that is, in truth, very, very easy to love."Buffalo News

-

“[Gioia] walks fans through a crash course in jazz appreciation that’s suitable for newcomers and intermediate listeners alike…His prose is…inviting and often playful… Most valuable is the extensive catalogue of recommendations, not just of the genre’s top performers but of 150 contemporary jazz musicians—a list that new fans can use to kickstart their journey, and experienced ones can reference to keep up with the form’s continuing evolution.”Publishers Weekly

-

"How to Listen to Jazz is a fresh, clearly written and infinitely usable book that should put the jazz novice on track."Library Journal

-

"A pretense-free primer on learning to appreciate jazz.... Curious neophytes can start here."Mojo

-

"As jazz enters its second century, becoming more multi-faceted apace, guidance for the novice--listener or musician--is more useful than ever, and Ted Gioia offers it expertly, in blessedly readable prose."Dan Morgenstern, Director emeritus, Institute of Jazz Studies and author of Living with Jazz

-

"This book does what so many have tried to and failed: it teaches without preaching and empowers the reader to search for their own understanding and preferences. It's a welcome and needed addition to everyone's bookshelf."Wayne Winborne, Executive Director, Institute of Jazz Studies

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use