By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

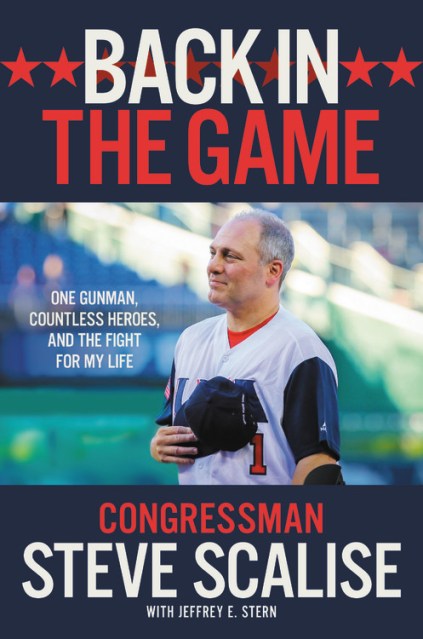

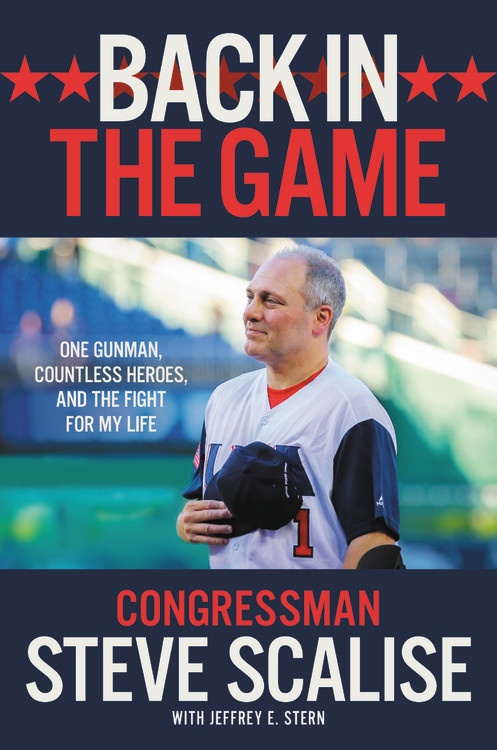

Back in the Game

One Gunman, Countless Heroes, and the Fight for My Life

Contributors

With Jeffrey E Stern

Read by Steve Scalise

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 13, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549173158

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On the morning of June 14, 2017, at a practice field for the annual Congressional Baseball Game, a man opened fire on the Republican team, wounding five and nearly killing Louisiana congressman Steve Scalise.

In heart-pounding fashion, Scalise’s minute-by-minute account tells not just his own harrowing story, but the stories of heroes who emerged in the seconds after the shooting began and worked to save his life and the lives of his colleagues and teammates.

Scalise delves into the backgrounds of each hero, seeking to understand how everyone wound up right where they needed to be, right when they needed to be there, and in possession of just the knowledge and experience they needed in order to save his life. Scalise takes us through each miracle, and each person who experienced it. He brings us the story of Rep. Brad Wenstrup, an Army Reserve officer and surgeon whose combat experience in Iraq uniquely prepared him for the attack that morning; of the members of his security detail, who acted with nearly cinematic courage; of the police, paramedics, helicopter pilots, and trauma team who came together to save his life.

Most important, it tells of the citizens from all over America who came together in ways big and small to help one grateful man, and whose prayers lifted up Scalise during the worst days of his hospitalization. As we follow the gripping, poignant, and ultimately inspiring story, we begin to realize what Scalise learned firsthand in real time: that Americans look out for each other, and that there is far more uniting us than dividing us.

-

"This is a heart pounding moment by moment account of what happened on the baseball diamond and a much deeper examination of who we are as Americans and what we must do to tone down the hateful rhetoric in today's political conversations."Newsmax

-

"The firefight described in Back in the Game had me on the edge of my seat."Townhall

-

"The gripping and inspiring story about the June 14, 2017 assassination attempt on him and other members of the House Republican baseball team."Washington Examiner

-

"A must-read for all Americans! Despite being targeted and nearly killed for his political beliefs, Steve Scalise came back stronger than ever to keep fighting for our values. He's a true conservative leader, and his story is powerful."Sean Hannity

-

"Riveting! Steve's story can be a lesson for all of us about unity, bridging divides, and how family and friends are what's most important in life."Congressman Cedric Richmond, D-LA

-

"Steve's faith, from the moment of his injury throughout his recovery, is a powerful example to us all, as he and his family trump over the evil that found us on the field that day."Congressman Brad Wenstrup, R-OH

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use