Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

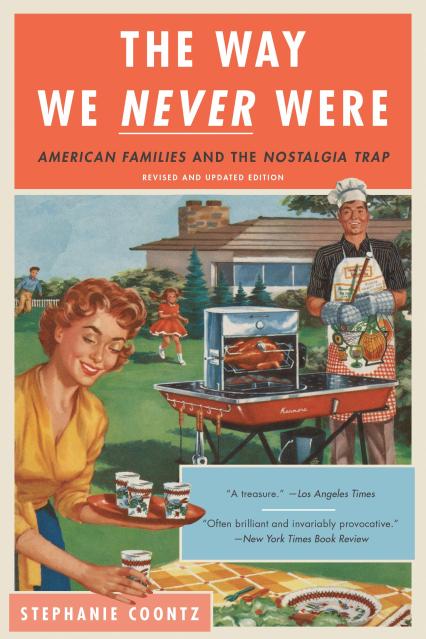

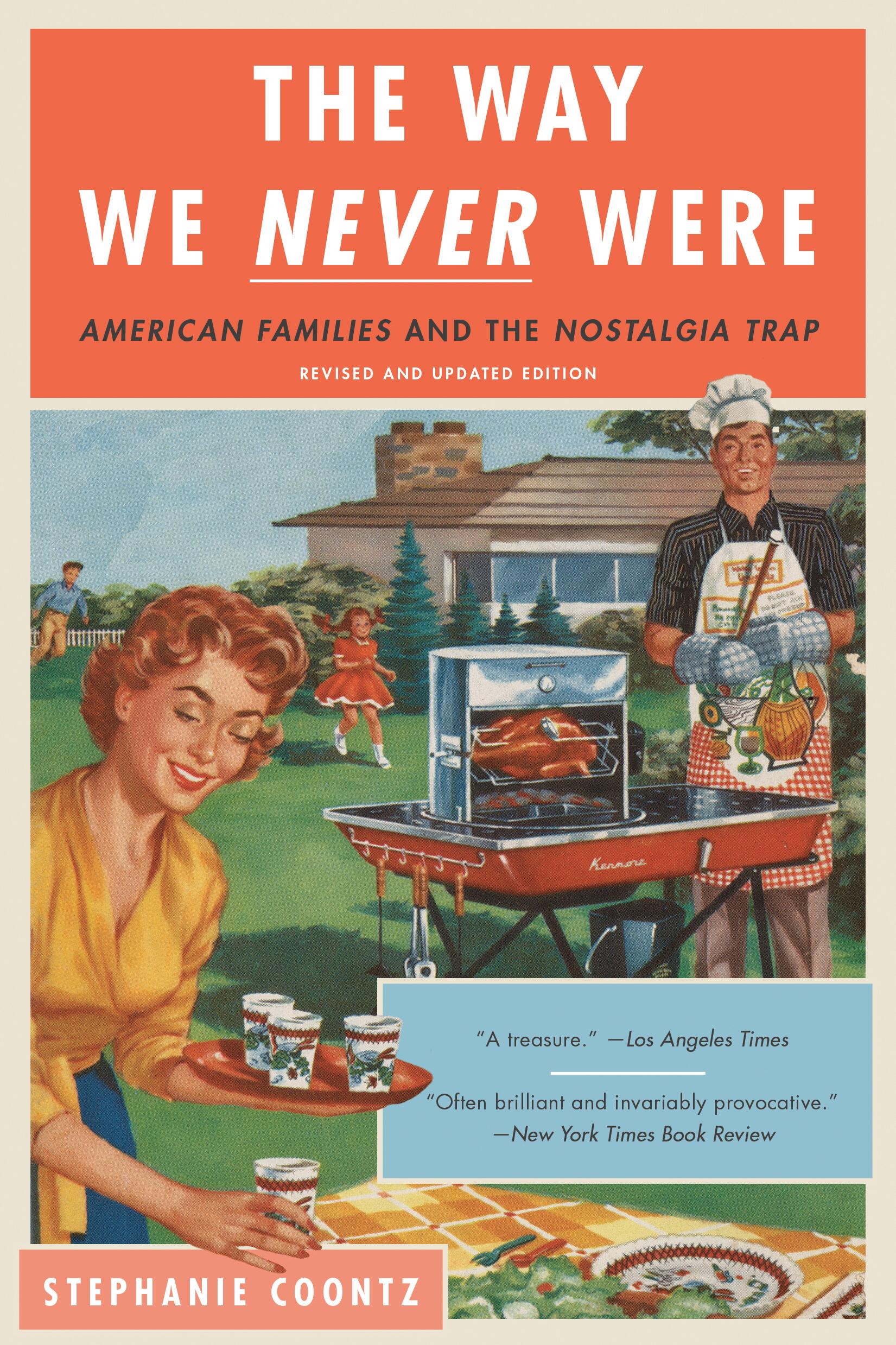

The Way We Never Were

American Families and the Nostalgia Trap

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2016

- Page Count

- 576 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465098842

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Digital download $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“The Way We Never Were effectively demolishes the normal, traditional nuclear family as neither normal nor traditional, and not even nuclear.” ―Nation

Leave It to Beaver was not a documentary, a man’s home has never been his castle, the “male breadwinner marriage” is the least traditional family in history, and rape and sexual assault were far higher in the 1970s than they are today. In The Way We Never Were, acclaimed historian Stephanie Coontz examines two centuries of the American family, sweeping away misconceptions about the past that cloud current debates about domestic life. The 1950s do not present a workable model of how to conduct our personal lives today, Coontz argues, and neither does any other era from our cultural past. Coontz explores how the clash between growing gender equality and rising economic inequality is reshaping family life, marriage, and male-female relationships in our modern era.

Now more relevant than ever, The Way We Never Were is a potent corrective to dangerous nostalgia for an American tradition that never really existed.

-

“A treasure.”Los Angeles Times

-

“Often brilliant and invariably provocative.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Coontz approaches the subject of what we now insist up on calling ‘family values’ with what is, in the current atmosphere, a refreshing lack of partisan cant.”Jonathan Yardley, Washington Post Book World

-

“Historically rich, and loaded with anecdotal evidence, The Way We Never Were effectively demolishes the normal, traditional nuclear family as neither normal nor traditional, and not even nuclear.”Nation

-

“Coontz presents fascinating facts and figures that explode the cherished myths about self-sufficient, happy, moral families.”Newsday

-

“Coontz’s strength is in the way she shows that families of every era have been blamed for conditions beyond their control.”San Francisco Chronicle

-

“A wonderfully perceptive, myth-debunking report .... An important contribution to the current debate on family values.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Clear, incisive, and distinguished by Coontz’s personal conviction and by its vast range of cogent examples, including capsule histories of women in the labor force and of black families. Fascinating, persuasive, politically relevant.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“Coontz persuasively dispels the myths and stereotypes of ‘traditional’ family values as the product of the postwar era.”Library Journal

-

“Stephanie Coontz is a national treasure. Her work, always solidly grounded in the best and most comprehensive research, is consistently groundbreaking. She changes the way we understand the past, present, and the future. What’s more, her new paradigms change the way we live and work!”Ellen Galinsky, president, Families and Work Institute

-

“Stephanie Coontz has her finger on the pulse of contemporary families like no one else in America.”Paula England, 2015 President, American Sociological Association