Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

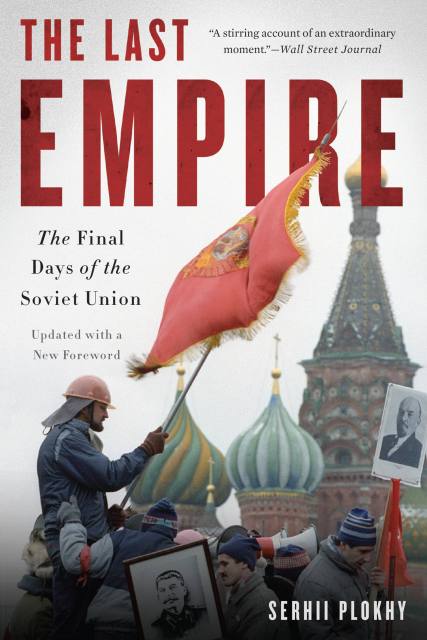

The Last Empire

The Final Days of the Soviet Union

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 8, 2015

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465097920

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 8, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On Christmas Day, 1991, President George H. W. Bush addressed the nation to declare an American victory in the Cold War: earlier that day Mikhail Gorbachev had resigned as the first and last Soviet president. The enshrining of that narrative, one in which the end of the Cold War was linked to the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the triumph of democratic values over communism, took center stage in American public discourse immediately after Bush's speech and has persisted for decades — with disastrous consequences for American standing in the world.

As prize-winning historian Serhii Plokhy reveals in The Last Empire, the collapse of the Soviet Union was anything but the handiwork of the United States. Bush, in fact, was firmly committed to supporting Gorbachev as he attempted to hold together the USSR in the face of growing independence movements in its republics. Drawing on recently declassified documents and original interviews with key participants, Plokhy presents a bold new interpretation of the Soviet Union's final months, providing invaluable insight into the origins of the current Russian-Ukrainian conflict and the outset of the most dangerous crisis in East-West relations since the end of the Cold War.

Winner of the Lionel Gelber Prize

Winner of the Pushkin House Russian Book Prize

Choice Outstanding Academic Title

BBC History Magazine Best History Book of the Year

-

"A superb read: a deeply researched, indispensable reappraisal of the fall of the USSR that has the nail-biting drama of a movie, the gripping narrative and colorful personalities of a novel, and the analysis and original sources of a work of scholarship."Simon Sebag Montefiore, BBC History Magazine (Best History Books of the Year)

-

“A stirring account of an extraordinary moment…what elevates The Last Empire from solid history to the must-read shelf is its relevance to the current crisis.”Wall Street Journal

-

"Using recently released documents, Plokhy traces in fascinating detail the complex events that led to the Soviet Union's implosion."Foreign Affairs

-

"A fine-grained, closely reported, highly readable account of the upheavals of 1991."Financial Times

-

"Plokhy makes a convincing case that the misplaced triumphalism of the senior Bush's administration led to the disastrous hubris of his son's."Slate

-

"A fascinating and readable deep dive into the final half-year of the Soviet Union."Sunday Telegraph (UK)

-

"A superb work of scholarship, vividly written, that challenges tired old assumptions with fresh material from East and West, as well as revealing interviews with many major players."Spectator (UK)

-

"An incisive account of the five months leading up to the Union's dissolution.... His vibrant, fast-paced narrative style captures the story superbly."Sunday Times (UK)

-

"Almost a day-by-day, blow-by-blow account of the actions and reactions of the main figures.... Very relevant to today's Ukrainian crisis...very well recounted."Literary Review (UK)

-

"Serhii Plokhy's great achievement in this wonderfully well-written account is to show that much of the triumphalist transatlantic view of the Soviet collapse is historiographical manure."Times of London (UK)

-

Times Literary Supplement

"Plokhy does a good job of debunking much of the conventional wisdom, especially prevalent in the United States, about the American role in the break-up of the Soviet Union.... His setting the record straight is also of more than historiographical significance." -

"A meticulously documented chronicle of the evil empire's demise.... [Plokhy] is the voice Ukrainians have been yearning for."Ukrainian Weekly

-

"With Crimea annexed and eastern Ukraine starting to break away to Russia, The Last Empire may be the most timely book of the year."National Review

-

"One of a rare breed: a well-balanced, unbiased book written on the fall of Soviet Union that emphasizes expert research and analysis."Publishers Weekly

-

"[Plokhy] provides fascinating details (especially concerning Ukraine) about this fraught, historic time."Kirkus