Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

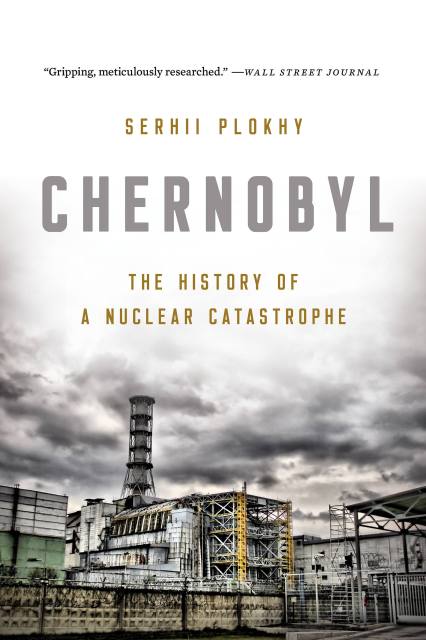

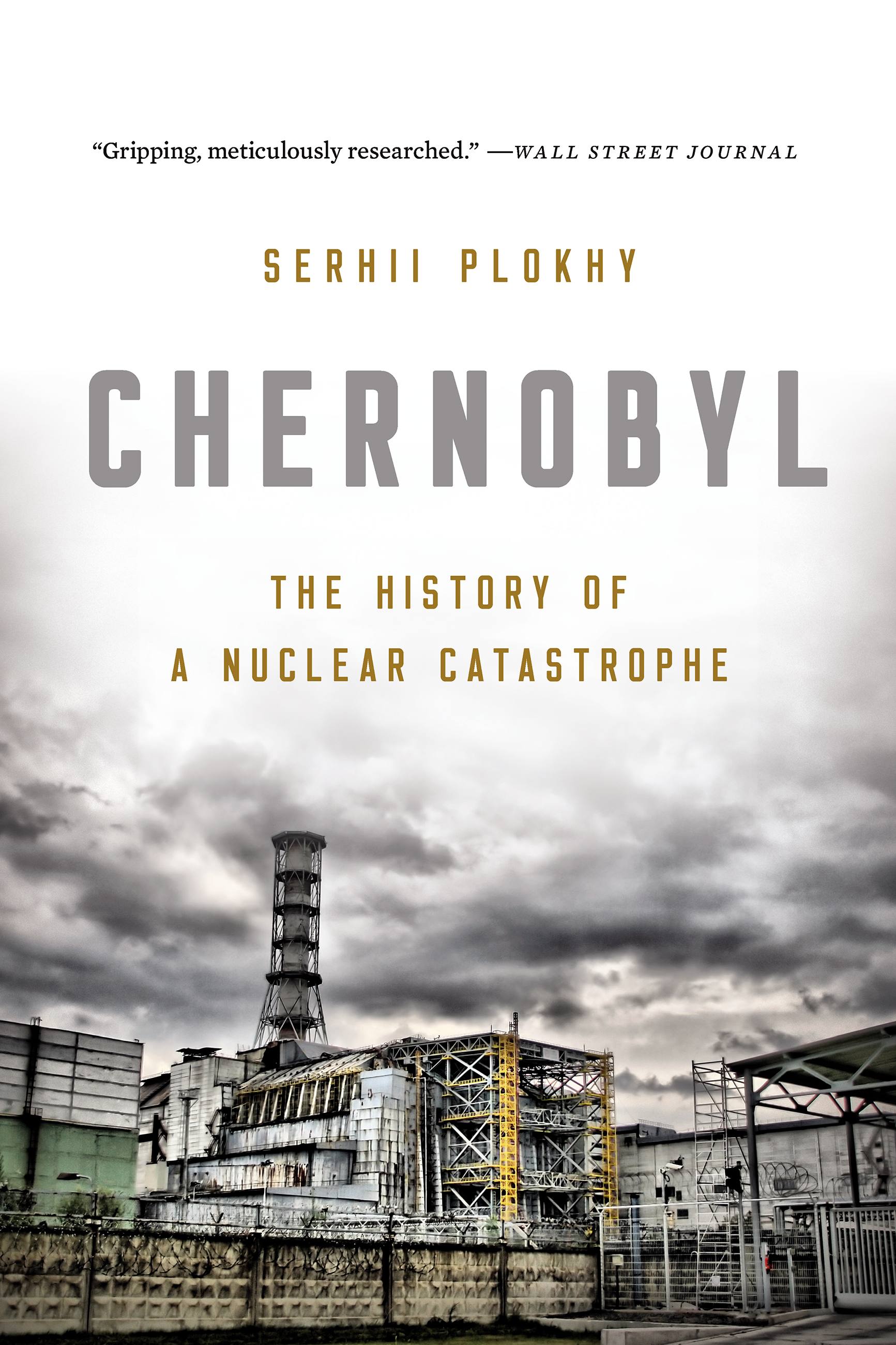

Chernobyl

The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541617087

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On the morning of April 26, 1986, Europe witnessed the worst nuclear disaster in history: the explosion of a reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine. Dozens died of radiation poisoning, fallout contaminated half the continent, and thousands fell ill.

In Chernobyl, Serhii Plokhy draws on new sources to tell the dramatic stories of the firefighters, scientists, and soldiers who heroically extinguished the nuclear inferno. He lays bare the flaws of the Soviet nuclear industry, tracing the disaster to the authoritarian character of the Communist party rule, the regime's control over scientific information, and its emphasis on economic development over all else.

Today, the risk of another Chernobyl looms in the mismanagement of nuclear power in the developing world. A moving and definitive account, Chernobyl is also an urgent call to action.