By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

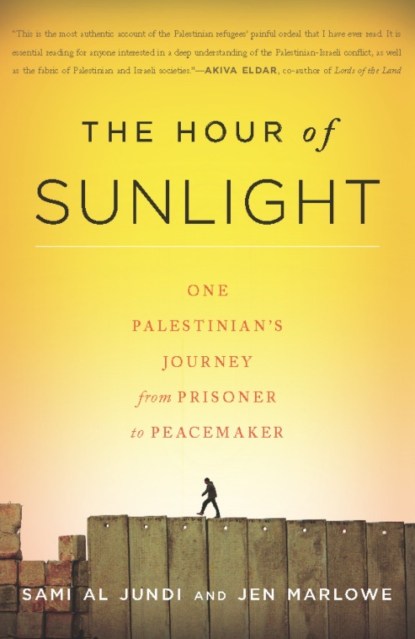

The Hour of Sunlight

One Palestinian's Journey from Prisoner to Peacemaker

Contributors

By Jen Marlowe

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 1, 2011

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568586311

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 1, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It was in an Israeli jail that his unlikely transformation began. Al Jundi was welcomed into a highly organized, democratic community of political prisoners who required that members of their cell read, engage in political discourse on topics ranging from global revolutions to the precepts of nonviolent protest and revolution.

Al Jundi left prison still determined to fight for his people’s rights — but with a very different notion of how to undertake that struggle. He cofounded the Middle East program of Seeds of Peace Center for Coexistence, which brings together Palestinian and Israeli youth.

Marked by honesty and compassion for Palestinians and Israelis alike, The Hour of Sunlight illuminates the Palestinian experience through the story of one man’s struggle for peace.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use