By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

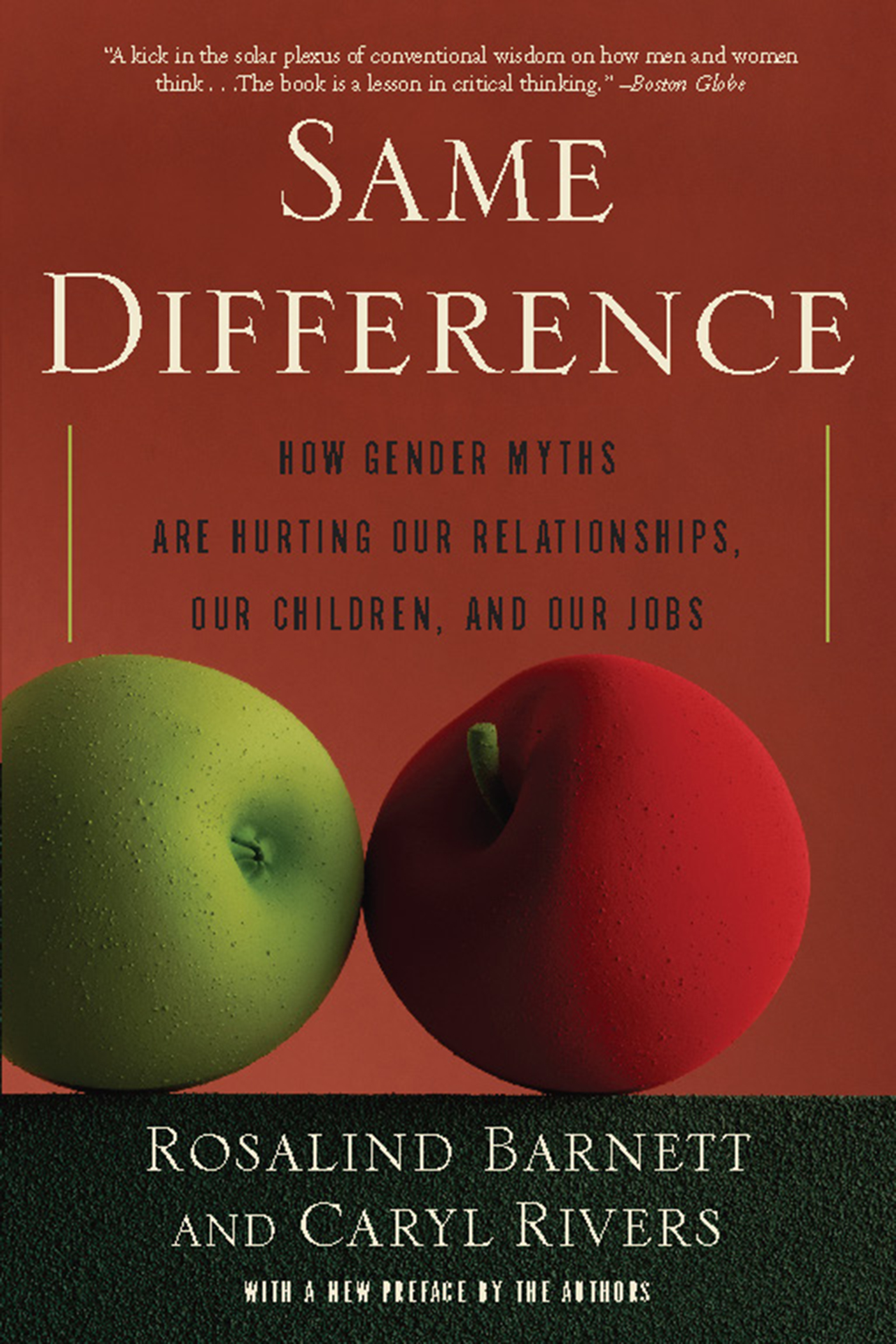

Same Difference

How Gender Myths Are Hurting Our Relationships, Our Children, and Our Jobs

Contributors

By Caryl Rivers

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 25, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786737895

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 25, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From respected academics like Carol Gilligan to pop-psych gurus like John Gray, and even the controversial Harvard President Lawrence Summers, the message has long been the same: Men and women are fundamentally different, and trying to bridge the gender gap can only lead to grief. But as the New York Times Book Review raved, Barnett and Rivers “debunk these theories in a no-nonsense way, offering a refreshingly direct (i.e. unashamedly judgmental) critique of traditional parental roles, tututting at the couples they interviewed who cling to stereotyped ideas of the family.” “Blending case histories, new research and thoughtful analysis, the writers describe the divide between the sexes as a crevice, not a chasm. The good news: We’re all a lot more flexible than the gender clich8Es let on.”-Psychology Today