By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Rick Steves Snapshot Northern Ireland

Contributors

By Rick Steves

By Pat O’Connor

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 31, 2023

- Page Count

- 136 pages

- Publisher

- Rick Steves

- ISBN-13

- 9781641715294

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 31, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

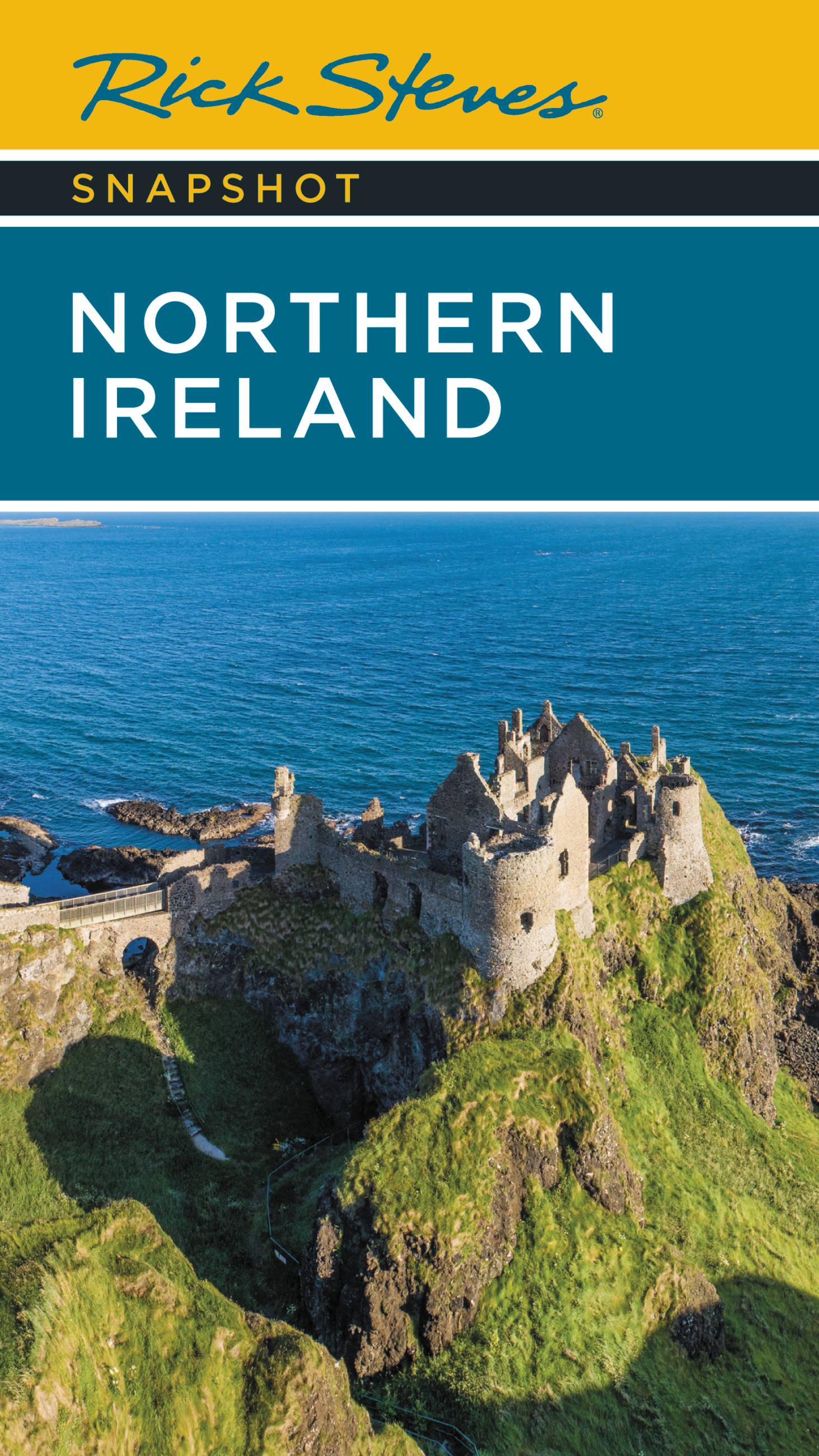

- Rick’s firsthand, up-to-date advice on the best sights, restaurants, hotels, and more in Northern Ireland, plus tips to beat the crowds, skip the lines, and avoid tourist traps

- Top sights and local experiences: Tour the Dunluce Castle or Giant’s Causeway along the Antrim Coast, spend a day marveling at zoology specimens and ancient treasures at the Ulster Museum in Belfast, and contemplate Derry’s political murals

- Helpful maps and self-guided walking tours to keep you on track

Exploring further? Pick up Rick Steves Ireland for comprehensive coverage, detailed itineraries, and essential information.

Genre:

-

"The country's foremost expert in European travel for Americans."Forbes

-

"Steves is an absolute master at unlocking the hidden gems of the world's greatest cities, towns, and monuments."USA Today

-

“Every country-specific travel guidebook from the Rick Steves publishing empire can be counted upon for clear organization, specificity and timeliness."Society of American Travel Writers

-

"Pick the best accommodations and restaurants from Rick Steves…and a traveler searching for good values will seldom go wrong or be blindsided."NBC News

-

"His guidebooks are approachable, silly, and even subtly provocative in their insistence that Americans show respect for the people and places they are visiting and not the other way around."The New Yorker

-

"Travel, to Steves, is not some frivolous luxury—it is an engine for improving humankind, for connecting people and removing their prejudices, for knocking distant cultures together to make unlikely sparks of joy and insight. Given that millions of people have encountered the work of Steves over the last 40 years, on TV or online or in his guidebooks, and that they have carried those lessons to untold other millions of people, it is fair to say that his life’s work has had a real effect on the collective life of our planet."The New York Times Magazine

-

"[Rick Steves] laces his guides with short and vivid histories and a scholar's appreciation for Renaissance art yet knows the best place to start an early tapas crawl in Madrid if you have kids. His clear, hand-drawn maps are Pentagon-worthy; his hints about how to go directly to the best stuff at the Uffizi, avoid the crowds at Versailles and save money everywhere are guilt-free."TIME Magazine

-

"Steves is a walking, talking European encyclopedia who yearns to inspire Americans to venture 'beyond Orlando.'"Forbes

-

“…he’s become the unofficial guide for entire generations of North American travelers, beloved for his earnest attitude and dad jeans."Outside Magazine

-

"His books offer the equivalent of a bus tour without the bus, with boiled-down itineraries and step-by-step instructions on where to go and how to get there, but adding a dash of humor and an element of choice that his travelers find empowering."The New York Times

-

"His penchant for creating meaningful experiences for travelers to Europe is as passionate as his inclination for making ethical choices his guiding light."Forbes

-

"[Rick Steves'] neighborhood walks are always fun and informative. His museum guides, complete with commentary about historic sculpture and storied artworks are wonderful and add another dimension to sometimes stodgy, hard-to-comprehend museums."NBC News

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use