By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

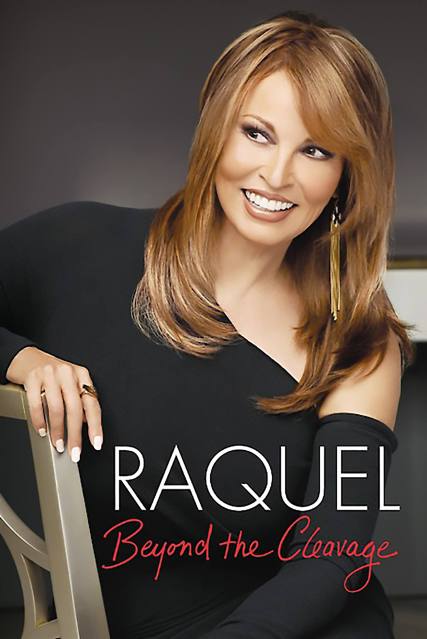

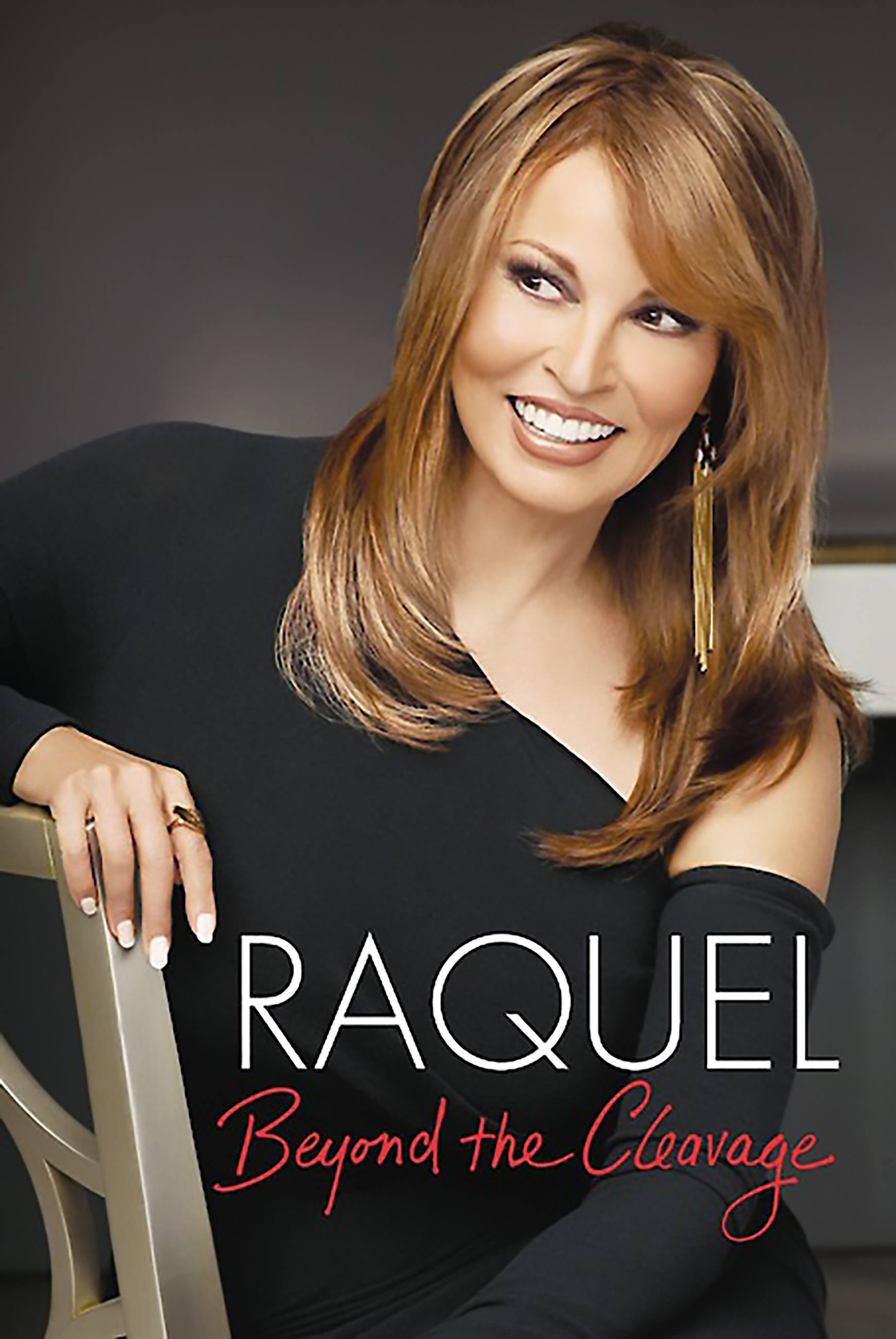

Raquel: Beyond the Cleavage

Contributors

By Raquel Welch

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 29, 2011

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781602861367

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 29, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

She didn’t hatch out of an eagle’s nest, circa One Million Years B.C., clad in a skimpy fur bikini. She didn’t aspire to fame as a sex symbol. Yet, for many years after making her Hollywood entrance as every man’s fantasy, Raquel Welch was best known for her beauty and sex appeal. A private person, she allowed people to draw their own conclusions from her public image. Here, Raquel Welch spoke her mind. And, with the luxury of hindsight and the benefit of experience, she had plenty to share about the art of being a woman—even men will find it enlightening to read about what made her tick.

In Beyond the Cleavage, Raquel Welch talked about her views on all that comes with being a member of the female sex—love, sex, style, health, body image, career, family, forgiveness, aging, and coming of age. Looking back on her life, she let women in on her childhood, dominated by a volatile father; her first love, marriage, and divorce; her early struggles as a single working mother in Hollywood; her battles for roles and respect as an actress; and her daring decision never to lie about her age. Looking forward, she offered women a compass to guide them at every crossroad of life, from menopause through the empty nest years, to dating younger men and beyond. Along with bringing baby boomers into her confidence—she offered essential tips for staying motivated and positive past fifty, as well as divulging her secrets for fabulous hair and makeup—she even talked to today’s younger generation of women about the importance of carrying themselves with dignity and self-respect.

With warmth, humor, conviction, and honesty, Raquel revealed her approach to preventative aging, her life-changing commitment to yoga, her recipe for eating right, her skincare regimen, her flair for fashion, and much more. Deeply personal (Welch wrote every word herself—no ghostwriter), Beyond the Cleavage was Raquel Welch’s gift to every woman who longs to look and feel her best, and be at peace with herself.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use