By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

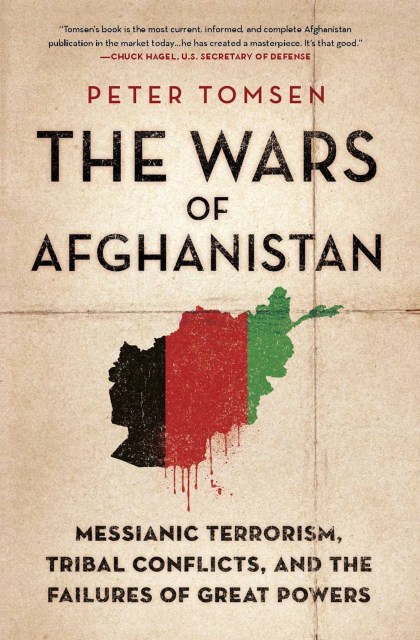

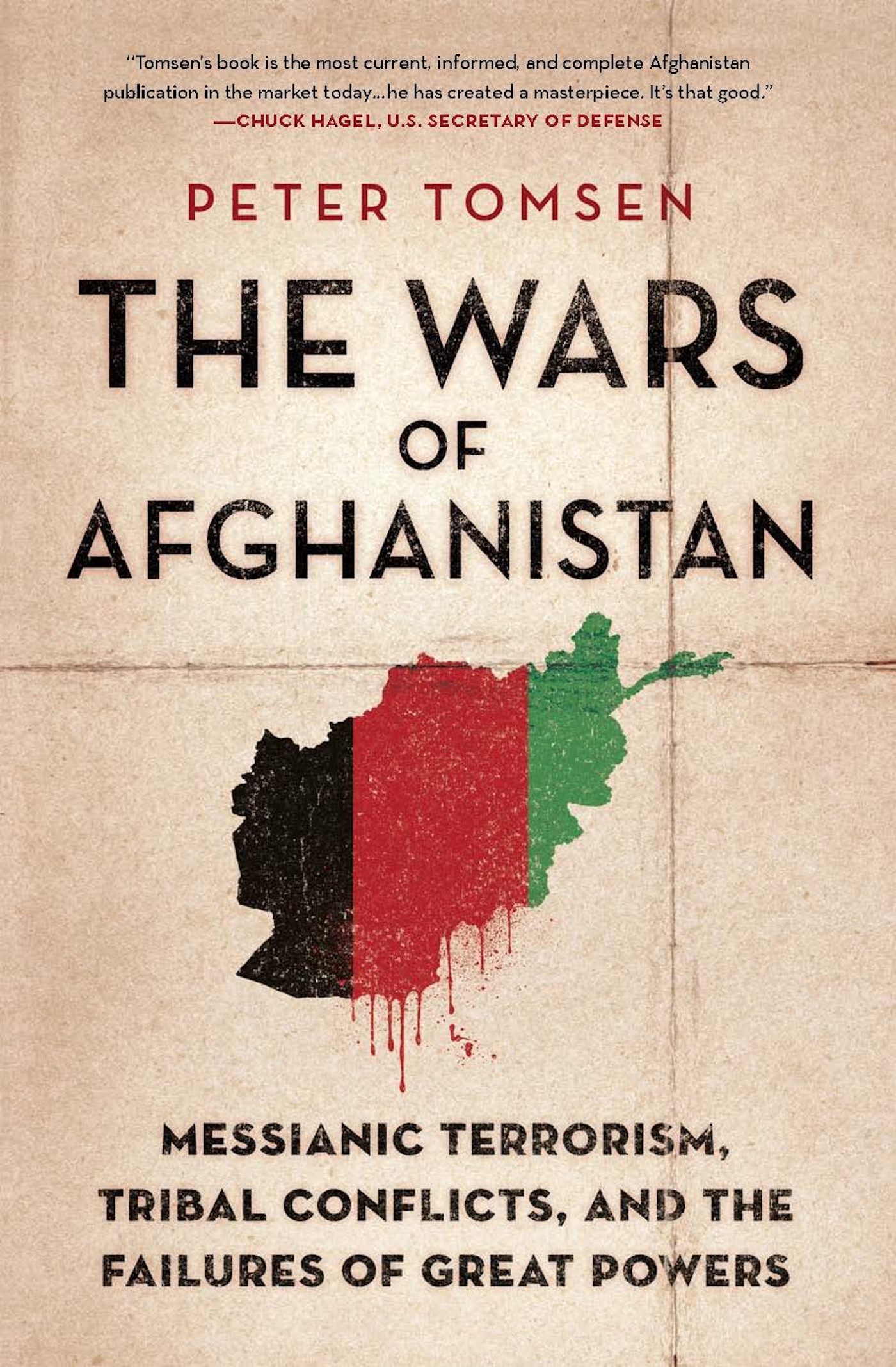

The Wars of Afghanistan

Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers

Contributors

By Peter Tomsen

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 10, 2013

- Page Count

- 912 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610394123

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $29.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 10, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This book offers a deeply informed perspective on how Afghanistan’s history as a “shatter zone” for foreign invaders and its tribal society have shaped the modern Afghan narrative. It brings to life the appallingly misinformed secret operations by foreign intelligence agencies, including the Soviet NKVD and KGB, the Pakistani ISI, and the CIA.

American policy makers, Tomsen argues, still do not understand Afghanistan; nor do they appreciate how the CIA’s covert operations and the Pentagon’s military strategy have strengthened extremism in the country. At this critical time, he shows how the U.S. and the coalition it leads can assist the region back to peace and stability.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use