Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

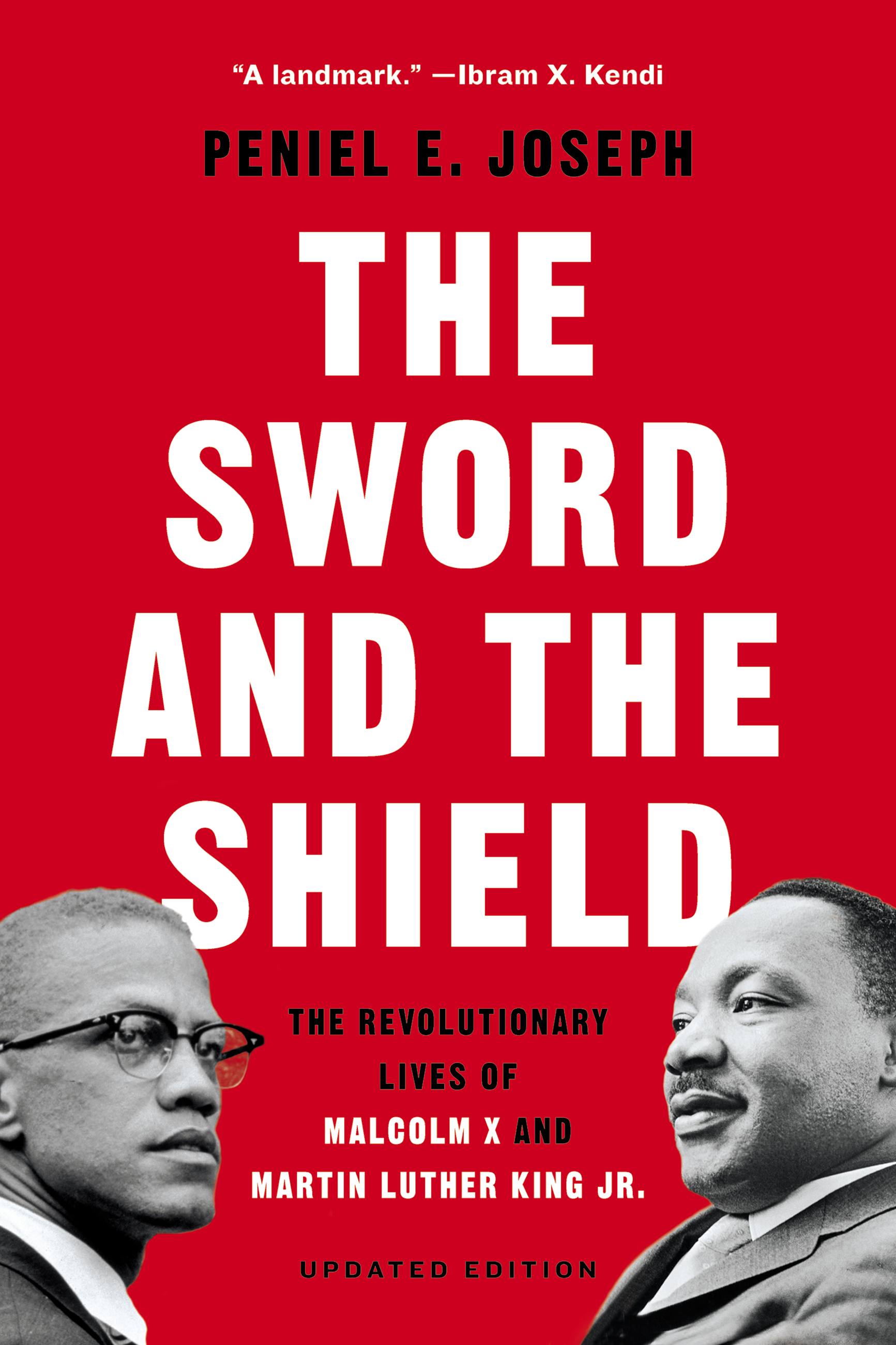

The Sword and the Shield

The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541617858

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This dual biography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King transforms our understanding of the twentieth century’s most iconic African American leaders.

"A fascinating story, full of subtle twists and turns." —Washington Post

To most Americans, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. represent contrasting ideals: self-defense versus nonviolence, Black Power versus civil rights, the sword versus the shield. The struggle for Black freedom is wrought with the same contrasts. While nonviolent direct action is remembered as an unassailable part of American democracy, the movement’s militancy is either vilified or erased outright.

In The Sword and the Shield, Peniel E. Joseph upends these misconceptions and reveals a nuanced portrait of two men who, despite markedly different backgrounds, inspired and pushed each other throughout their adult lives. This is a strikingly revisionist account of Malcolm and Martin, the era they defined, and their lasting impact on today’s Movement for Black Lives.

"A fascinating story, full of subtle twists and turns." —Washington Post

To most Americans, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. represent contrasting ideals: self-defense versus nonviolence, Black Power versus civil rights, the sword versus the shield. The struggle for Black freedom is wrought with the same contrasts. While nonviolent direct action is remembered as an unassailable part of American democracy, the movement’s militancy is either vilified or erased outright.

In The Sword and the Shield, Peniel E. Joseph upends these misconceptions and reveals a nuanced portrait of two men who, despite markedly different backgrounds, inspired and pushed each other throughout their adult lives. This is a strikingly revisionist account of Malcolm and Martin, the era they defined, and their lasting impact on today’s Movement for Black Lives.

-

"Enchanting."New York Times

-

“Joseph, a prolific historian of twentieth-century African-American politics, an indefatigable public commentator, and arguably the leading chronicler of the Black Power movement, sheds light in The Sword and the Shield on the complex intellectual and strategic dynamics beneath the publicly fractious relationship between Martin and Malcolm.”New York Review of Books

-

"Mr. Joseph, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, weaves [Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X's] stories fluidly and with vivid detail, helping to strip away the high gloss of mythology."Wall Street Journal

-

"It is a fascinating story, full of subtle twists and turns."Washington Post

-

“A brilliant revisionist study of the lives of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Effectively challenging the conventional dichotomy between the two men, it shows, instead, how their paths became increasingly convergent, coming to represent ‘overlapping and intersecting strains of revolutionary black activism.’”The Guardian

-

“In the year of Black Lives Matter, this comparative biography of two of the great figures in the struggle for racial equality in the US stands out.”Financial Times

-

"Joseph's fresh and perceptive dual biography may rekindle political unity in a time of increasingly granular identity politics, sensationalism, and fear."Booklist

-

"As the author delineates the philosophies and tactics of each man, he compares and contrasts them on nearly every page, making the various narrative strands cohere nicely. An authoritative dual biography from a leading scholar of African American history."Kirkus

-

"The Sword and the Shield is a landmark. It is what happens when one America's greatest historians of African America shines the same light on two of African America's greatest historical figures. Peniel Joseph deploys his supreme talents as a biographer and movement historian to interweave the world-shattering lives of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X."Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist

-

"Arguing against facile juxtapositions of the political philosophies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Peniel Joseph has written a powerful and persuasive re-examination of these iconic figures, tracing the evolution of both men's activism. The Sword and the Shield provides a nuanced analysis of these figures' political positions in addition to unfolding the narratives of their personal lives. Well-written and compelling, this important new book brilliantly explores the commonalities between the political goals of Malcolm and Martin."Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor, Harvard University

-

"The Sword and The Shield is a masterwork of bold historical revisionism that will change how we think of the dynamic relationship between Harlem's Hero Malcolm X, and America's Apostle Martin Luther King, Jr. By probing their distinctive styles of social combat, and by examining the historical contexts of their evolving, complex and often interrelated philosophies of race and political transformation, Joseph shows how each man was bigger than the sum of his competing symbolic parts. Joseph destroys the one-dimensional views of their ideological conflicts, and roots both figures in the cultural milieu and racial maelstrom that marked the age they inherited and shaped. By showing how Malcolm and Martin started as adversaries, then became rivals, and eventually, on occasion, unwitting compatriots in global black resistance to oppression, Joseph brilliantly illumines the defining personalities at the heart of the black freedom struggle during the height of its revolutionary expression in American history."Michael Eric Dyson, author of Jay-Z: Made in America

-

"In this brilliant, timely, and eloquently written dual biography, Peniel E. Joseph, a leading scholar of the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power era, not only demonstrates his command over Malcolm X's and Martin Luther King Jr.'s activism and thought, but also his penetrating understanding of the black freedom struggle and the times and events that inevitably shaped his subjects. A profound and important book, The Sword and the Shield will shape how future generations interpret Malcolm's and King's monumental contributions to American culture, politics, and democracy."Pero G. Dagbovie, author of Reclaiming the Black Past: The Use and Misuse of African American History in the Twenty-First Century

-

"Peniel Joseph is an omnivore historian with a gift for synthesizing fact and ideas into a vivid, accessible package. In The Sword and the Shield, he has reconciled two dissonant icons in a satisfying, intimate blend of narrative and insight."Diane McWhorter, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution

-

"Peniel Joseph has written the civil rights history for our time. He explains how partisanship has distorted the legacy of a movement that promoted the citizenship and dignity of all Americans. Joseph recounts how the iconic civil rights leaders worked in tandem to unleash the common potential of American democracy, and how we must all do the same today. This is a deep book that will move readers to action."Jeremi Suri, author of The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America's Highest Office