By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The Social Transformation of American Medicine

The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry

Contributors

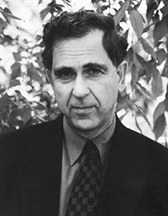

By Paul Starr

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 30, 2017

- Page Count

- 592 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093038

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Revised) $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $25.00 $31.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Considered the definitive history of the American health care system, The Social Transformation of American Medicine examines how the roles of doctors, hospitals, health plans, and government programs have evolved over the last two and a half centuries. How did the financially insecure medical profession of the nineteenth century become a prosperous one in the twentieth? Why was national health insurance blocked? And why are corporate institutions taking over our medical system today? Beginning in 1760 and coming up to the present day, renowned sociologist Paul Starr traces the decline of professional sovereignty in medicine, the political struggles over health care, and the rise of a corporate system.

Updated with a new preface and an epilogue analyzing developments since the early 1980s, The Social Transformation of American Medicine is a must-read for anyone concerned about the future of our fraught health care system.

Genre:

-

"The definitive social history of the medical profession in America....A monumental achievement."New York Times Book Review

-

"Superb sociology, superior history--and essential reading for anyone interested in the fate of American medicine."Newsweek

-

"The most ambitious and important analysis of American medicine to appear in over a decade.... If you read only one book about American medicine, this is the one you should read."Ronald Numbers, author of The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use