By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

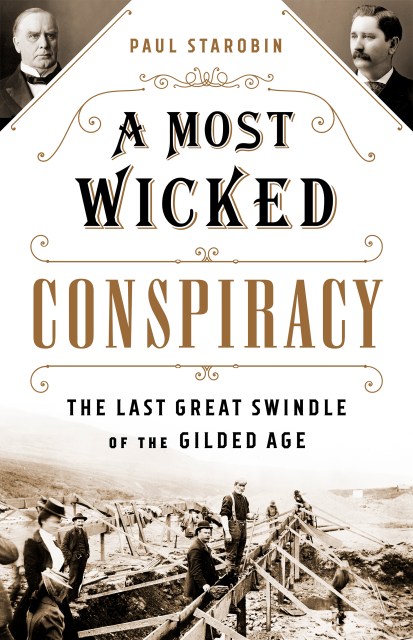

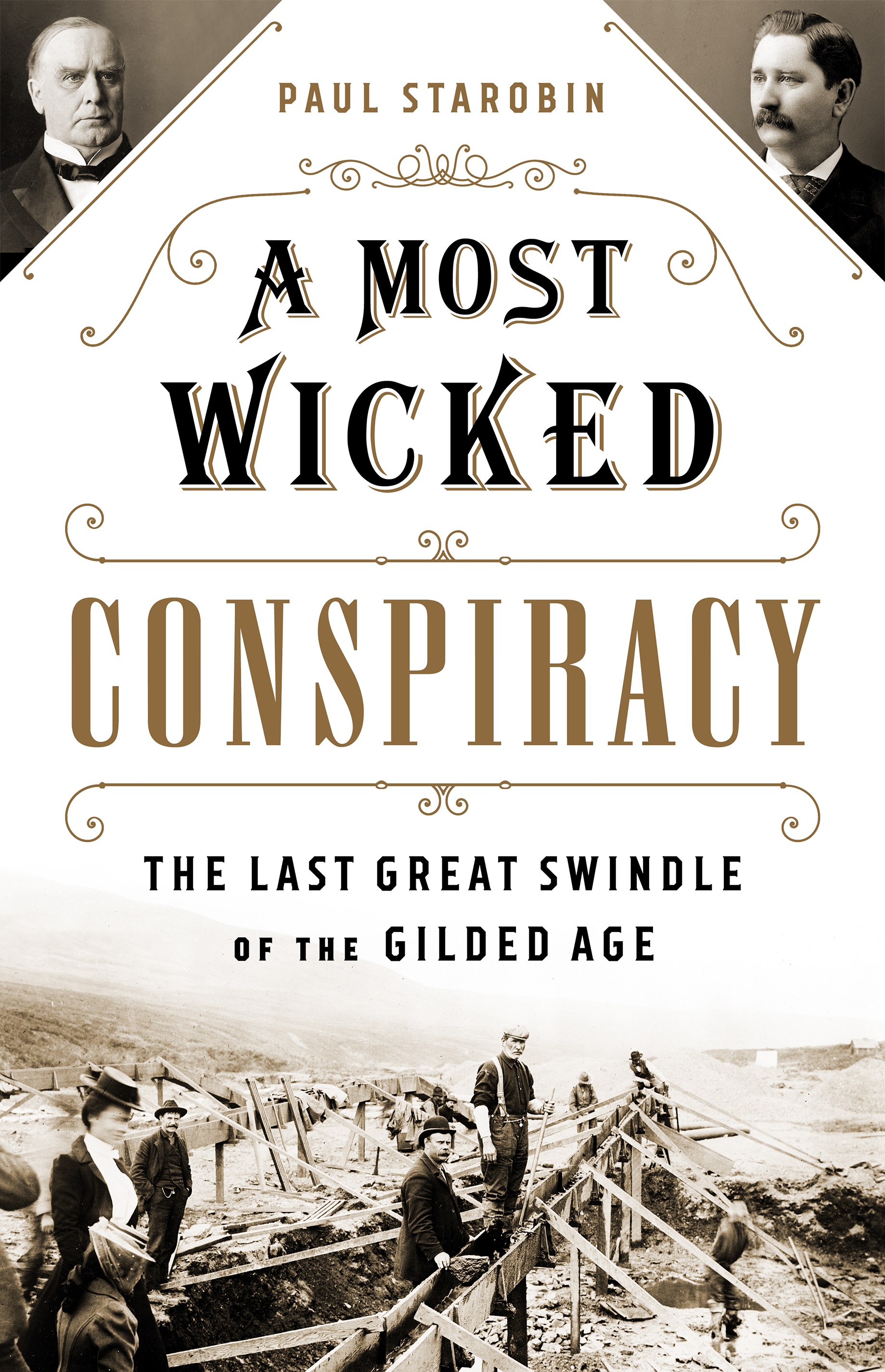

A Most Wicked Conspiracy

The Last Great Swindle of the Gilded Age

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 30, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742291

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 30, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A tale of Gilded Age corruption and greed from the frontier of Alaska to America’s capital.

In the feverish, money-making age of railroad barons, political machines, and gold rushes, corruption was the rule, not the exception. Yet the Republican mogul “Big Alex” McKenzie defied even the era’s standard for avarice. Charismatic and shameless, he arrived in the new Alaskan territory intent on controlling gold mines and draining them of their ore. Miners who had rushed to the frozen tundra to strike gold were appalled at his unabashed deviousness.

A Most Wicked Conspiracy recounts McKenzie’s plot to rob the gold fields. It’s a story of how America’s political and economic life was in the grip of domineering, self-dealing, seemingly-untouchable party bosses in cahoots with robber barons, Senators and even Presidents. Yet it is also the tale of a righteous resistance of working-class miners, muckraking journalists, and courageous judges who fought to expose a conspiracy and reassert the rule of law.

Through a bold set of characters and a captivating narrative, Paul Starobin examines power and rampant corruption during a pivotal time in America, drawing undoubted parallels with present-day politics and society.

A Most Wicked Conspiracy recounts McKenzie’s plot to rob the gold fields. It’s a story of how America’s political and economic life was in the grip of domineering, self-dealing, seemingly-untouchable party bosses in cahoots with robber barons, Senators and even Presidents. Yet it is also the tale of a righteous resistance of working-class miners, muckraking journalists, and courageous judges who fought to expose a conspiracy and reassert the rule of law.

Through a bold set of characters and a captivating narrative, Paul Starobin examines power and rampant corruption during a pivotal time in America, drawing undoubted parallels with present-day politics and society.

-

"Well-researched and entertaining, A Most Wicked Conspiracy is an impressive accomplishment."Historical Novels Society

-

"Entertaining....Sturdy research and clear prose reveal some truly abominable snowmen wreaking havoc in Alaska."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Into this narrative Mr. Starobin skillfully weaves the political evolution of Alaska, purchased from Russia in 1867, and the insidious rise of nativism at the turn of the century....In his lively account of the Nome conspiracy, Mr. Starobin takes satisfaction in the outcome: Even during the Gilded Age's rampant capitalism, the American justice system prevented McKenzie from looting Alaska."Wall Street Journal

-

"Thoroughly-researched and skillfully-written...It's a story well worth telling, and Paul Starobin tells it very well indeed."Washington Times

-

"Starobin tells a jaunty tale of jaw-dropping greed at the dawn of the 20th century."Associated Press

-

"...this book is important. If we do not study and remember our history, we are doomed to repeat it... This book also serves as a hopeful reminder that ultimately there are people who will stand up for what is right."Minneapolis Star Tribune

-

"Starobin keeps the drama flowing."Booklist

-

"Most stories labeled unknown are quite well known, but Paul Starobin bares an audacious and largely forgotten swindle that implicated prominent politicians, corporate leaders, and handpicked judges in an attempt to rob ordinary Alaskan miners of the fruits of their labor. An intriguing and well-told tale of avarice and greed that reveals how corrupt American business and government were in the Gilded Age."Richard White, Emeritus Professor of American History at Stanford University and author of The Republic for Which It Stands - The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896

-

"The Gilded Age at its gaudiest, Alaska at its most demanding, human nature at its . . . most human. A rollicking tale with sobering lessons for today."H.W. Brands, Professor; Jack S. Blanton Sr. Chair in History at University of Texas, Austin

-

"In this vivid tale, Paul Starobin takes us back to a time when American dynamism and imagination came head-to-head with chicanery and fraud. Set in the wild Alaskan gold fields, the struggle of enterprising miners against the greed of swindlers and the corruption of public officials provided a fit coda to the Gilded Age and offers a warning for our own time."Jack Kelly, author of The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America

-

"In this anatomy of a swindle, Starobin clearly relishes the tale he brings to life and separates the colorful victimizers from their victims, patiently evoking the lives of both in atmospheric detail...this cautionary story is a pleasure to read."Los Angeles Review of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use