Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

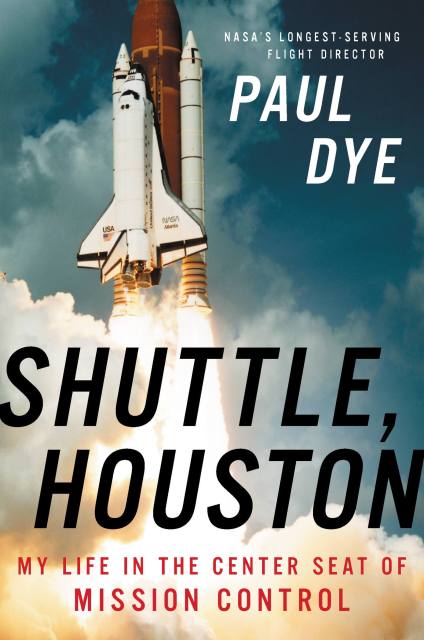

Shuttle, Houston

My Life in the Center Seat of Mission Control

Contributors

By Paul Dye

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316454575

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the longest-serving Flight Director in NASA’s history comes a revealing account of high-stakes Mission Control work and the Space Shuttle program that has redefined our relationship with the universe.

A compelling look inside the Space Shuttle missions that helped lay the groundwork for the Space Age, Shuttle, Houston explores the determined personalities, technological miracles, and eleventh-hour saves that have given us human spaceflight.

Relaying stories of missions (and their grueling training) in vivid detail, Paul Dye, NASA’s longest-serving Flight Director, examines the split-second decisions that the directors and astronauts were forced to make in a field where mistakes are unthinkable, and where errors led to the loss of national resources — and more importantly one’s crew. Dye’s stories from the heart of Mission Control explain the mysteries of flying the Shuttle — from the powerful fiery ascent to the majesty of on-orbit operations to the high-speed and critical re-entry and landing of a hundred-ton glider.

The Space Shuttles flew 135 missions. Astronauts conducted space walks, captured satellites, and docked with the Mir Space Station, bringing space into our everyday life, from GPS to satellite TV. Shuttle, Houston puts readers in his own seat at Mission Control, the hub that made humanity’s leap into a new frontier possible.

Genre:

-

"An excellent portrait of Mission Control, the teams, and the later missions. This should be required reading for anyone aspiring to be part of human space flight, as well as all scientists, engineers, project managers of any kind, and anyone considering a career in a highly complex field or program."Gene Kranz, Former Flight Director, NASA, and author Failure Is Not an Option

-

"Paul Dye pulls back the curtain on what it takes to be a Flight Controller, then a Flight Director in Mission Control. Like him, I've been both. Shuttle, Houston should not only entertain the casual, interested reader, but it should be invaluable to anyone aspiring to work in the 'Center Seat' whether that's in Mission Control or any other business or leadership position."Milt Heflin, NASA 1966-2013, Retired, Johnson Space Center Chief Flight Director, 2001-2004, and coauthor of Go, Flight!

-

"I learned many of these lessons from Paul Dye as he taught me and two decades more of Mission Control leaders the ropes, in exactly these words! His guidance is as valuable today in any leadership setting as it always was."Paul Sean Hill, Retired NASA Flight Director and Director of Mission Operations, and author of Leadership from the Mission Control Room to the Boardroom

-

"Shuttle, Houston gives us tremendous insight on the Mission Control Center. Paul Dye captures the awe and amazement of being part of that team. His wonderful explanations of how everyone works together and his understanding of the science and history will fascinate anyone who appreciates the dynamic world of human space exploration."Shannon Lucid, former Astronaut

-

"Richly detailed with the author’s own experiences and recollections, Shuttle, Houston covers virtually every aspect of Mission Control. By the time you finish reading this book, you will feel like you just participated in an actual space mission….A very interesting read."National Space Society

-

"Terrific...a fascinating history of how America built and operated the most complex machine ever devised by man....Anyone who is interested in flying generally, the history of flight, or managing massive technical projects, will enjoy this read."Kitplanes

-

"Government or commercial, capsule or shuttle, crewed spaceflight require the support of a mission control to ensure a safe mission. Wherever that mission control may be located and however it looks, it requires the same rigor and attention to detail described in Dye's book to ensure success."The Space Review

-

"With a clear voice from the onset, Dye deftly crafts the story of his many years working on the Shuttle program around the broader story of NASA at that time.... We are afforded a glimpse of the inner workings of NASA, a rare treat...the book is somehow referential and personal, thanks to the author's excellent writing skills. Packed with fascinating anecdotes from each mission...for anyone with even a passing interest in human spaceflight, this is a must-read.”BBC Sky at Night Magazine

-

"Space history enthusiasts will relish this."AudioFile

-

"A passionate look at the U.S. space shuttle program....The author fondly recalls in scrupulous detail the highlights of his three-decade career as a top NASA flight controller... both engaging and informative....The author's simple anecdotes about everyday working life at mission control that make for the most readable, entertaining sections....Dye's memoir is a balanced mix of moments both banal and breathtaking."Kirkus Reviews

-

"A fascinating insight into the inner workings of NASA."Booklist

-

"Dye provides an insider view of historic events....This motivating book shows people succeeding at their best: smart, cooperative, innovative, and caring."Library Journal