Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

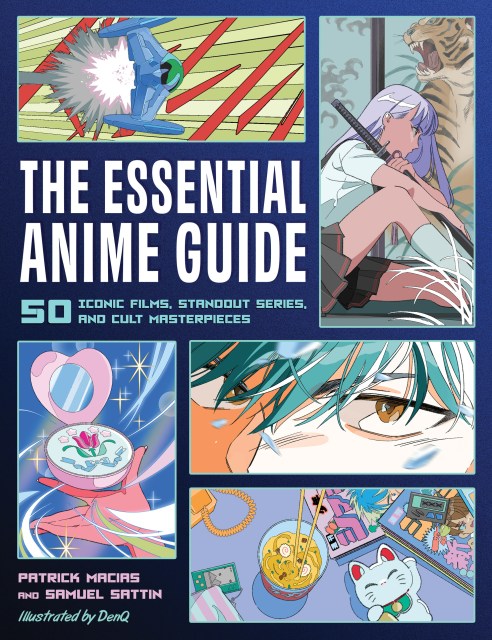

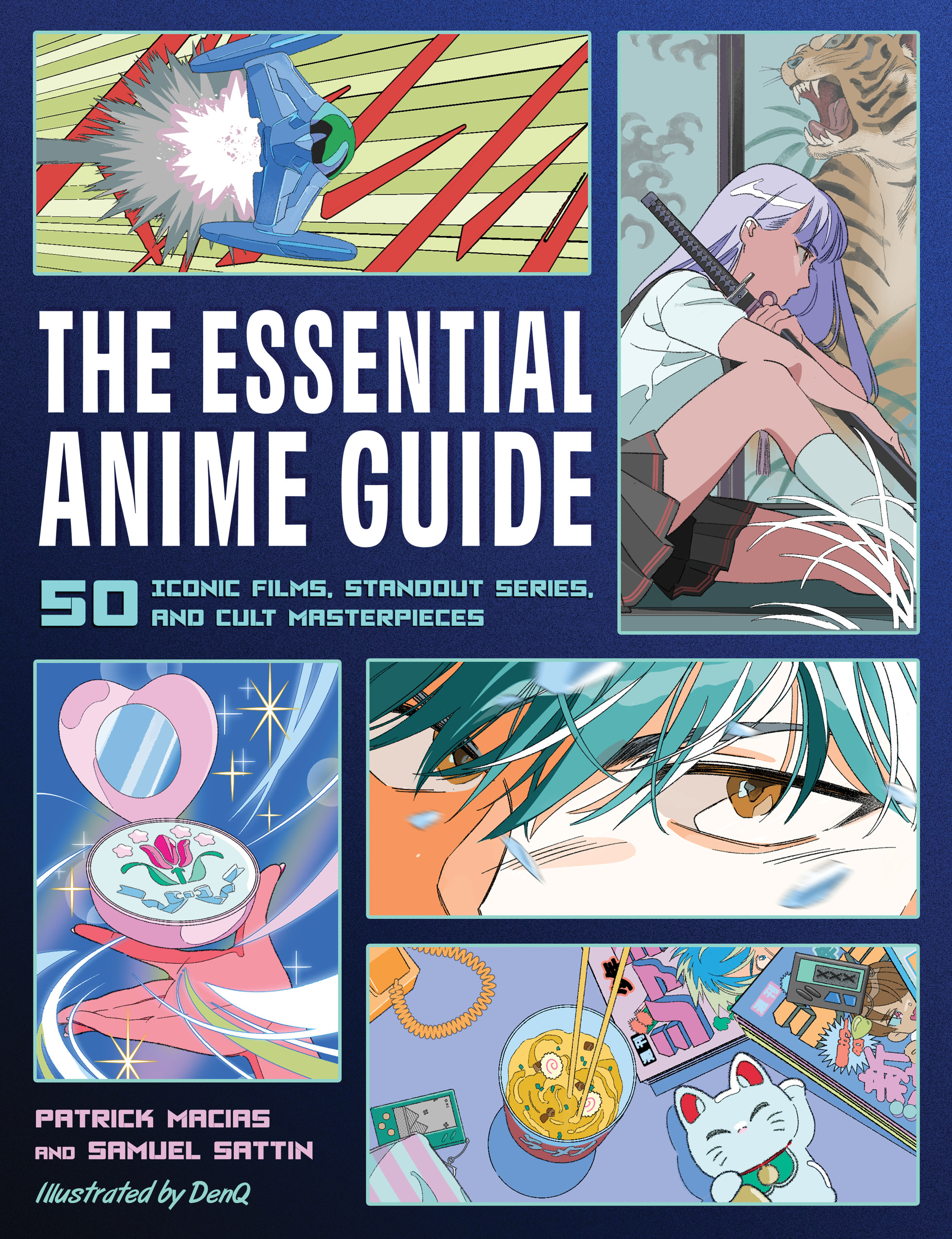

The Essential Anime Guide

50 Iconic Films, Standout Series, and Cult Masterpieces

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2023

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762484782

Price

$24.99Price

$31.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Essential Anime Guide is the guide every fan needs to the classic, must-see anime series and films that transformed both Japanese and Western pop culture. Organized by release date and with entries by experts in the anime field, this guide provides a comprehensive, behind-the-scenes look into the history and impact of these classic anime. Both casual fans and serious otaku alike will discover a fun and surprisingly touching portrait of the true impact of anime on pop culture.

Ranging from classic series to modern films, this official guide will explore iconic and must-see:

- Feature films: Akira (1988), Princess Mononoke (1997), Millennium Actress (2001), Metropolis (2001),Tekkonkinkreet (2006), Sword of the Stranger (2007), Summer Wars (2009), and Your Name (2016)

- Series: Astro Boy (1968), Lupin the 3rd (1967), Macross (1982), Ranma 1/2 (1989), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), Dragon Ball Z (1989), Sailor Moon (1992), Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997), Pokémon (1997), One Piece (1999), Fullmetal Alchemist (2003), K-On! (2007), Sword Art Online (2012), Yuri!! On Ice (2016), and My Hero Academia (2018)

- And many more!

-

"An effective primer that gives a behind-the-scenes look at some of anime’s most influential and popular works. Best for general readers and casual viewers. Dedicated fans might look elsewhere for less-mainstream selections."School Library Journal