By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

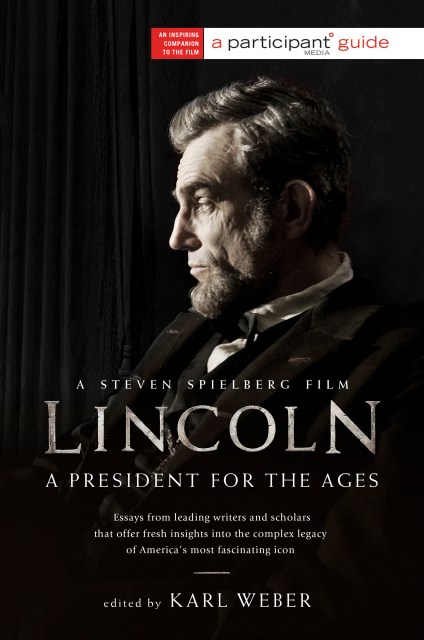

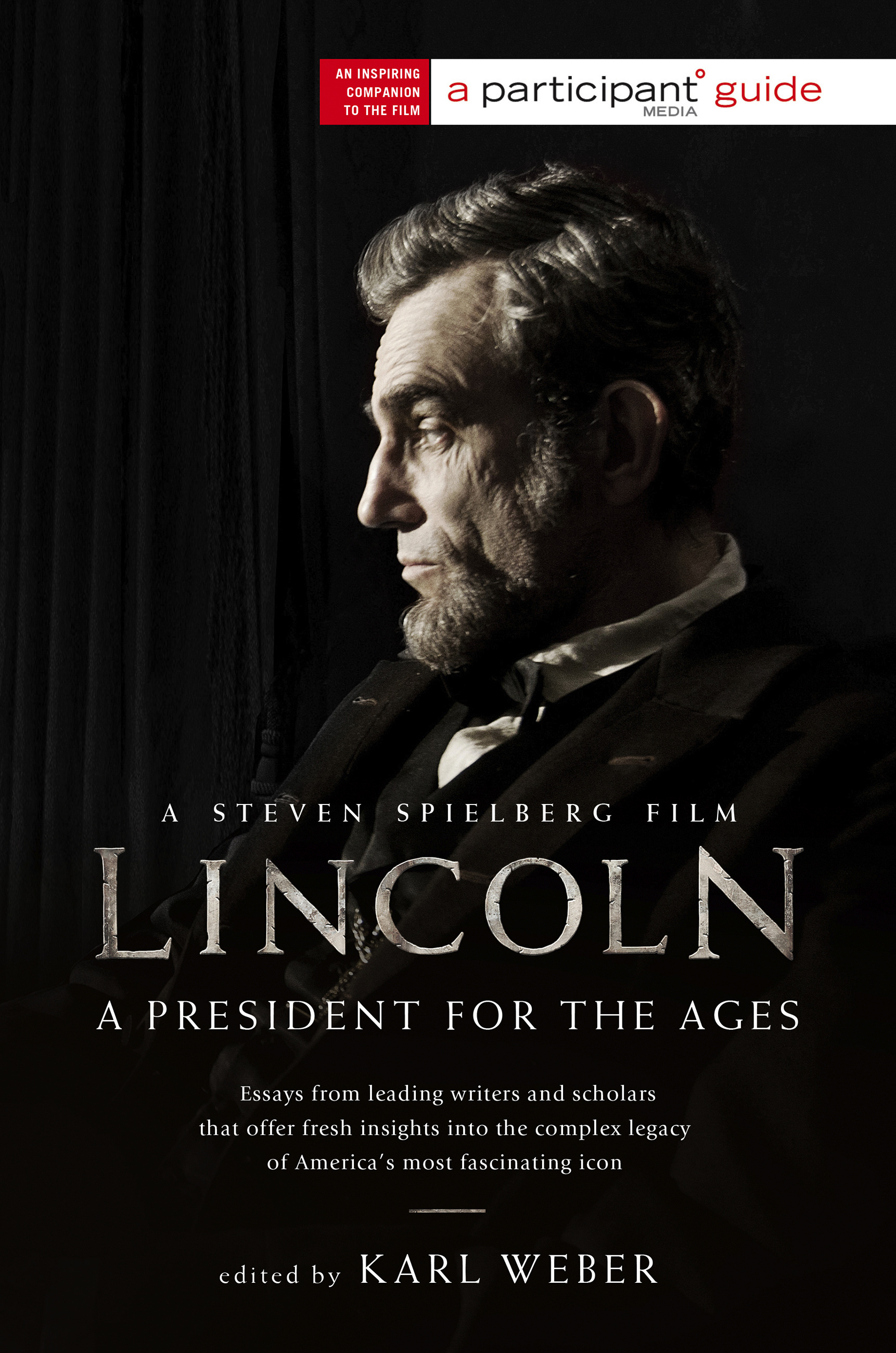

Lincoln

A President for the Ages

Contributors

By Participant

Edited by Karl Weber

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 30, 2012

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392631

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 30, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Timed to complement the new motion picture Lincoln, directed by Steven Spielberg, Lincoln: A President for the Ages introduces a new Lincoln grappling with some of history’s greatest challenges. Would Lincoln have dropped the bomb on Hiroshima? How would he conduct the War on Terror? Would he favor women’s suffrage or gay rights? Would today’s Lincoln be a star on Facebook and Twitter? Would he embrace the religious right — or denounce it?

The answers come from an all-star array of historians and scholars, including Jean Baker, Richard Carwardine, Dan Farber, Andrew Ferguson, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Allen C. Guelzo, Harold Holzer, James Malanowski, James Tackach, Frank J. Williams, and Douglas L. Wilson. Lincoln also features actor/activist Gloria Reuben describing how she played Elizabeth Keckley, the former-slave-turned-confidante of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln; and a selection of speeches and letters that explore little-known sides of Lincoln; “The Faces of Lincoln,” exploring his complex contemporary legacy.

Whether you’re a lifetime admirer of Lincoln or newly intrigued by his story, Lincoln: A President for the Ages offers a fascinating glimpse of his many-sided legacy.

-

Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright Tony Kushner, author of the screenplay for "Lincoln"

"I was delighted to read this collection of essays by people who have grappled with Lincoln and who’ve come to know him, each on her or his terms, and on Lincoln’s terms as well. Here are Lincolns that you’ll embrace, Lincolns you won’t recognize, Lincolns you'll be skeptical of or maybe angered by, and Lincolns who’ll add richness and depth to the Lincoln you already know."

Wall Street Journal

"The companion book to the coming film, Lincoln: A President for the Ages, asks great historians "What would Lincoln do?" in situations from Hiroshima to The Daily Show With Jon Stewart."

Huntington News

“In fact, it's an excellent one-volume introduction to Lincoln's political career.”

Civil War News

“Written by some of the country’s leading Lincoln scholars, these essays update our understanding of the 16th president as the Civil War community eagerly absorbs Spielberg’s new film.”

History Wire

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use