By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

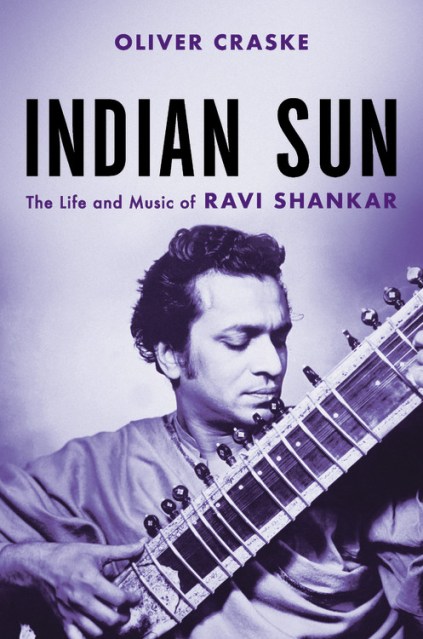

Indian Sun

The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 672 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306874888

Price

$32.00Format

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00

- ebook $17.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The definitive biography of Ravi Shankar, one of the most influential musicians and composers of the twentieth century, told with the cooperation of his estate, family, and friends

For over eight decades, Ravi Shankar was India’s greatest cultural ambassador. He was a groundbreaking performer and composer of Indian classical music, who brought the music and rich culture of India to the world’s leading concert halls and festivals, charting the map for those who followed in his footsteps. Renowned for playing Monterey Pop, Woodstock, and the Concert for Bangladesh-and for teaching George Harrison of The Beatles how to play the sitar-Shankar reshaped the musical landscape of the 1960s across pop, jazz, and classical music, and composed unforgettable scores for movies like Pather Panchali and Gandhi.

In Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar, writer Oliver Craske presents readers with the first full portrait of this legendary figure, revealing the personal and professional story of a musician who influenced-and continues to influence-countless artists. Craske paints a vivid picture of a captivating, restless workaholic-from his lonely and traumatic childhood in Varanasi to his youthful stardom in his brother’s dance troupe, from his intensive study of the sitar to his revival of India’s national music scene. Shankar’s musical influence spread across both genres and generations, and he developed close friendships with John Coltrane, Philip Glass, Yehudi Menuhin, George Harrison, and Benjamin Britten, among many others. For ninety-two years, Shankar lived an endlessly colorful and creative life, a life defined by musical, emotional, and spiritual quests-and his legacy lives on.

Benefiting from unprecedented access to Shankar’s archives, and drawing on new interviews with over 130 subjects-including his second wife and both of his daughters, Norah Jones and Anoushka Shankar- Indian Sun gives readers unparalleled insight into a man who transformed modern music as we know it today.

-

Best Classic Bands, "Best Music Books of the Year"

-

'...[A]n intimate, expert reading of Shankar's music, as well as revelatory access to create the definitive portrait of his context within modern culture."The Guardian

-

"A master receives masterly treatment... an outstanding, forensic and deeply sympathetic biography..."The Arts Desk

-

"[A] superlative biography... [A] masterly chronicle of a life teeming with all-too-human incident but heavenly inspiration."London Times

-

"The definitive biography of the Maestro, told with the cooperation of his estate, family, and friends. Rigorously researched and lovingly presented, Oliver Craske offers a detailed and compelling account of the life of Ravi Shankar and the worlds he touched through his music and personal journey."East Meets West Music

-

"...Craske handles the niceties of Shankar's personal life with diplomacy while staying focused on his subject's musical mission and lifelong hunger for spiritual fulfilment. He wears his expertise lightly and his passion on his sleeve: a winning combination for a definitive work."The Observer

-

'"Read as a whole, this book feels like an Indian version of A Dance to the Music of Time: the same characters bumping into each other over the course of nearly a century, relationships fraying and re-knitting, love affairs flaring, dying down, re-igniting, children repeating the mistakes of their parents, all against a backdrop of war and famine and independence and nationalism."The Spectator

-

"Oliver Craske's extraordinary biography Indian Sun... is not a hagiographic portrait of a spiritual icon but a remarkably human life story, defined by familial failures, seething rivalries, physical frailty and relentless ambition. For anyone who has been moved by a Shankar recording, this is a portrait of the man behind the music and the unchartered waters of Shankar's quest to save Indian classical music from extinction. With his elegant writing and extensive research, Craske manages to shatter Shankar's cliché Eastern sage persona and rebuild his reputation as one of the giants of world music. Indian Sun transcends its subject by becoming something larger than a narrow timeline of an undeniably large life. In using Shankar as an axis, Craske has written a broader cultural history of music and hyphenated artists in the 20th century - a measured rumination on the possibilities and the price of artistic ambition... this is a beautiful book, as resplendent as its subject's music and life."Washington Post

-

"Indian Sun is a new authoritative biography of the Indian musician Ravi Shankar's life, published to coincide with this year's centenary of his birth... Oliver Craske traces the full breadth of Shankar's life beyond the known flashpoints of his career."NPR's All Things Considered

-

"A definitive, meticulously truthful book, full of discoveries."BBC Radio 4 (Pick of the Week)

-

"A supremely readable biography that deftly interweaves his personal life, his professional life, and where necessary some brilliant analysis of his music and Indian music in general."Songlines

-

"Tells the personal and musical story of a life that changed so many musical cultures."BBC Radio 3's Music Matters

-

"A key virtue of this fine biography is that it mostly resists the tendency to idealise Shankar. When [Richard] Attenborough went to see India's prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in the early 1960s about his proposed film on Gandhi, Nehru advised him that it would be wrong to deify the Mahatma because 'he was too great a man for that.' Craske fruitfully follows the spirit of Nehru's advice."Sight & Sound

-

"[A] compelling, informative, and the definitive book on this musical legend."Library Journal

-

"Indian Sun... gives us a superb trove of detail, some of it astonishing... Mr. Craske is at his best when writing about the least-emphasized aspects of Shankar's career... Yet the book excels, too, in those areas of which we're already aware. Mr. Craske is eloquent on the appeal of the music itself, and explains superbly how the Indian and Western classical idioms are so unlike each other."Wall Street Journal

-

"[An] incredibly detailed and wonderfully written biography."World Music Institute newsletter

-

"Compelling and informative" (One of the "Best Arts Books of 2020")Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use