Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

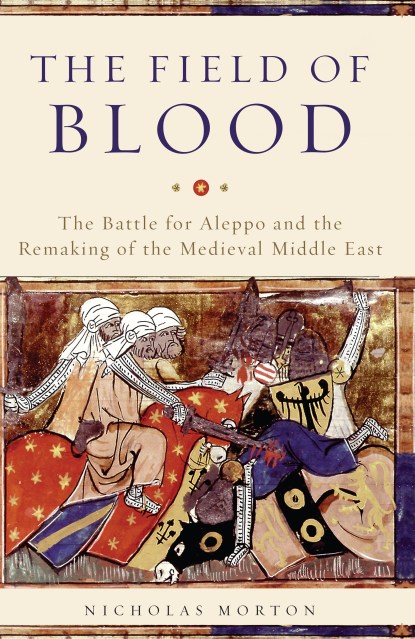

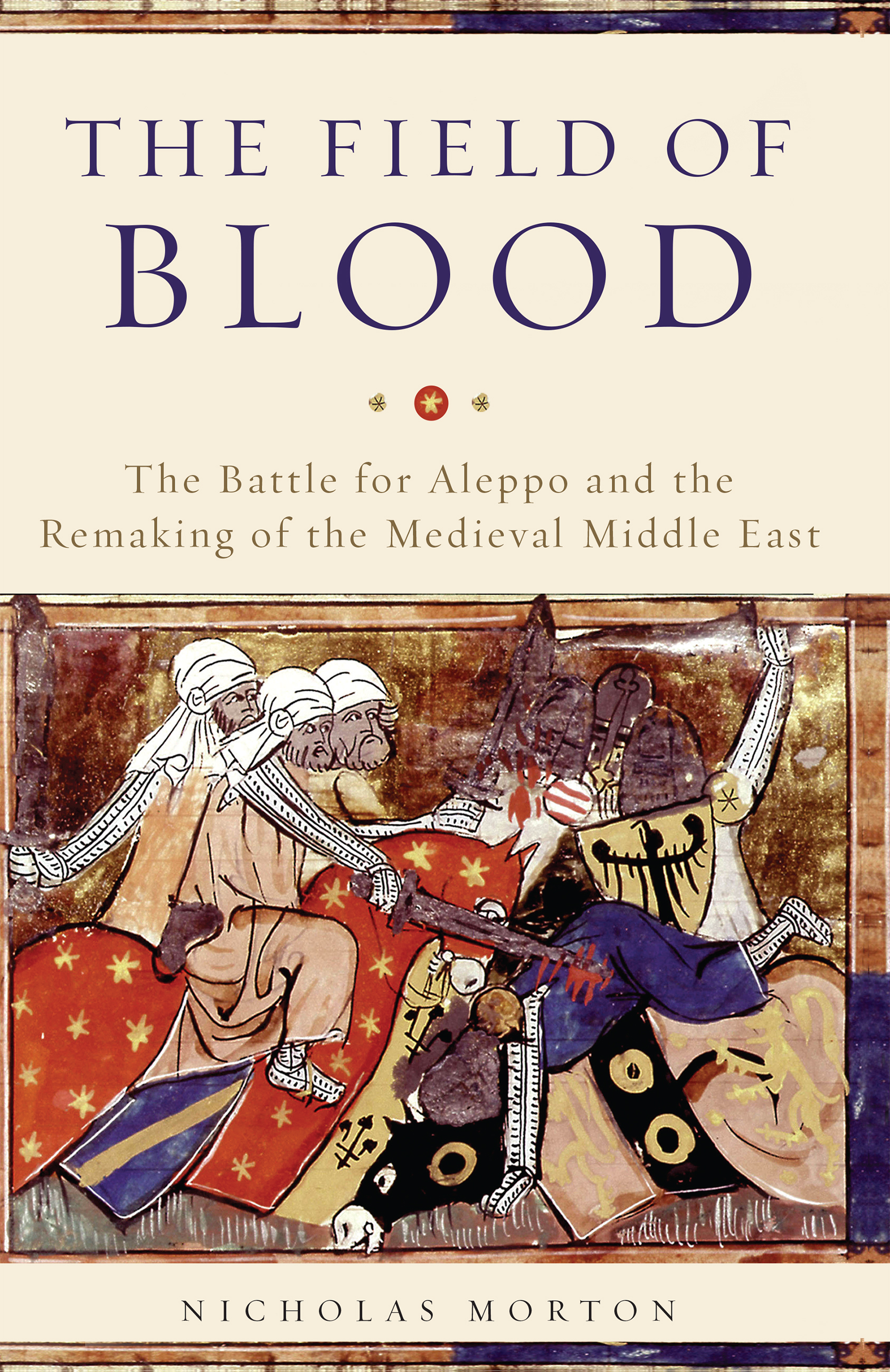

The Field of Blood

The Battle for Aleppo and the Remaking of the Medieval Middle East

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096701

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

During the First Crusade, Frankish armies swept across the Middle East, capturing major cities and setting up the Crusader States in the Levant. A sustained Western conquest of the region appeared utterly inevitable. Why, then, did the crusades ultimately fail?

To answer this question, historian Nicholas Morton focuses on a period of bitter conflict between the Franks and their Turkish enemies, when both factions were locked in a struggle for supremacy over the city of Aleppo. For the Franks, Aleppo was key to securing dominance over the entire region. For the Turks, this was nothing less than a battle for survival — without Aleppo they would have little hope of ever repelling the European invaders. This conflict came to a head at the Battle of the Field of Blood in 1199, and the face of the Middle East was forever changed.