Promotion

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

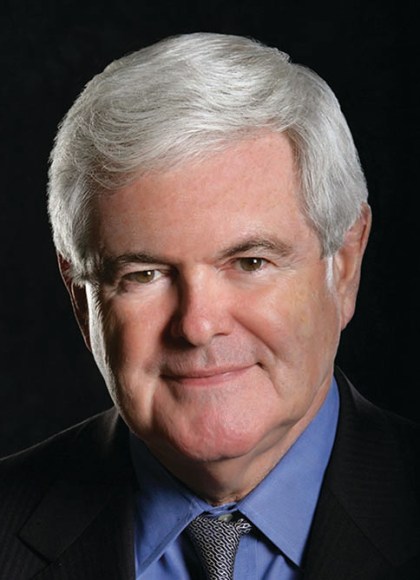

March to the Majority

The Real Story of the Republican Revolution

Contributors

With Joe Gaylord

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546004844

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The story of Gingrich’s rise from college professor, to architect of the Contract with America, to Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives is historic. There were many adventures, personalities, missteps, and victories on the road from a seemingly permanent House GOP minority to the first Republican majority in 40 years. These untold stories and inspiring lessons about the rise of modern conservatism are immensely relevant today as the United States faces profound and extraordinary challenges.

Newt Gingrich joins with former National Republican Congressional Committee Executive Director Joe Gaylord to bring alive the stories, events, and activities that led to the Contract with America and the first re-elected Republican majority since 1928. No two people are better positioned to tell this story than Gingrich and Gaylord. They were there, and they got it done.

Gingrich and Gaylord share never-before-told stories about:

• Ronald Reagan

• Richard Nixon

• Tip O’Neill

• George H.W. Bush

• Bill Clinton, and other fascinating political figures

March to the Majority is not only about the past, but also about the challenges our nation faces today and offers principles for governing the American people.

-

"Anyone who wants to understand how and why American politics are the way they are should read March to the Majority. This is the essential story of how a stale, seemingly permanent Democrat majority in Congress was defeated by a passionate group of men and women led by Newt Gingrich who wanted to change Washington and help Americans prosper.”Larry Kudlow, Host of Fox Business Network “Kudlow”

-

"Our nation is at a tipping point with a media bias and agency politicization unlike we have ever seen before, and we need to know where we've been to know where we're going and how best to get there; March to the Majority is the guide to get us back on track."Sean Hannity, host of The Sean Hannity Show and Fox News’ Hannity

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use