Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

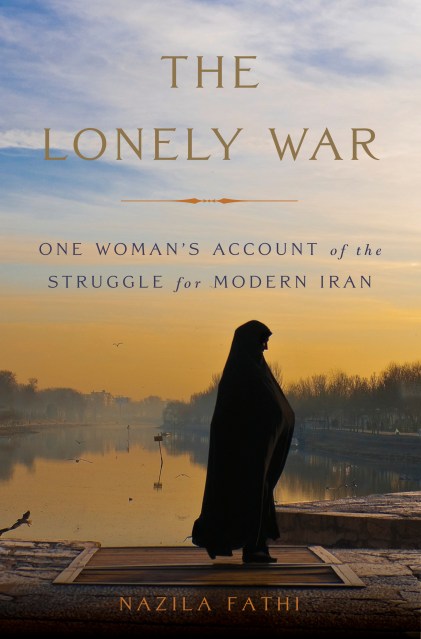

The Lonely War

One Woman's Account of the Struggle for Modern Iran

Contributors

By Nazila Fathi

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 14, 2014

- Page Count

- 360 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465040926

Price

$17.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 14, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In The Lonely War, Fathi interweaves her story with that of the country she left behind, showing how Iran is locked in a battle between hardliners and reformers that dates back to the country’s 1979 revolution. Fathi was nine years old when that uprising replaced the Iranian shah with a radical Islamic regime. Her father, an official at a government ministry, was fired for wearing a necktie and knowing English; to support his family he was forced to labor in an orchard hundreds of miles from Tehran. At the same time, the family’s destitute, uneducated housekeeper was able to retire and purchase a modern apartment — all because her family supported the new regime.

As Fathi shows, changes like these caused decades of inequality — especially for the poor and for women — to vanish overnight. Yet a new breed of tyranny took its place, as she discovered when she began her journalistic career. Fathi quickly confronted the upper limits of opportunity for women in the new Iran and earned the enmity of the country’s ruthless intelligence service. But while she and many other Iranians have fled for the safety of the West, millions of their middleclass countrymen — many of them the same people whom the regime once lifted out of poverty — continue pushing for more personal freedoms and a renewed relationship with the outside world.

Drawing on over two decades of reporting and extensive interviews with both ordinary Iranians and high-level officials before and since her departure, Fathi describes Iran’s awakening alongside her own, revealing how moderates are steadily retaking the country.