Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

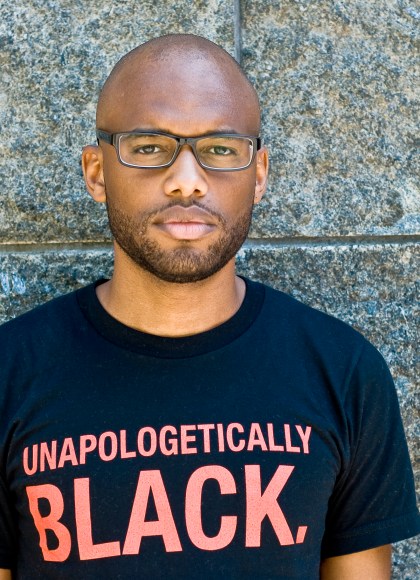

Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching

A Young Black Man's Education

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

How do you learn to be a black man in America? For young black men today, it means coming of age during the presidency of Barack Obama. It means witnessing the deaths of Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, and too many more. It means celebrating powerful moments of black self-determination for LeBron James, Dave Chappelle, and Frank Ocean.

In Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching, Mychal Denzel Smith chronicles his own personal and political education during these tumultuous years, describing his efforts to come into his own in a world that denied his humanity. Smith unapologetically upends reigning assumptions about black masculinity, rewriting the script for black manhood so that depression and anxiety aren’t considered taboo, and feminism and LGBTQ rights become part of the fight. The questions Smith asks in this book are urgent — for him, for the martyrs and the tokens, and for the Trayvons that could have been and are still waiting.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589770

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use