By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

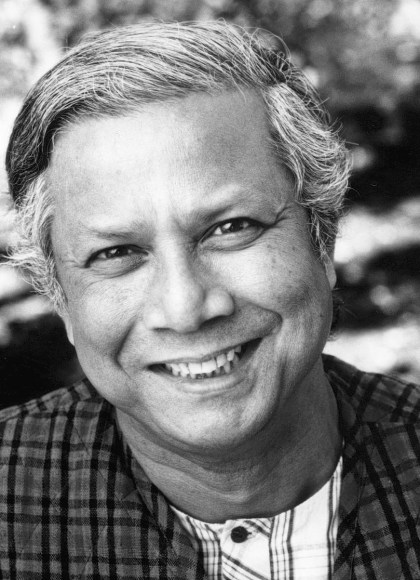

Building Social Business

The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity's Most Pressing Needs

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 11, 2010

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586488635

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 11, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Social business is a visionary new model for capitalism developed by Muhammad Yunus, the practical genius who pioneered microcredit and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to combat global poverty. Now social business, which harnesses the energy of capitalism to fulfill human needs rather than reward shareholders, is being adopted by leading corporations as well as entrepreneurs and social activists across Asia, South America, Europe, and the United States. Through examples of corporations such as BASF, Adidas, Danone, Uniqlo, and others, Building Social Business shows how an inspiring theory has become a world-altering practice, and offers practical guidance for those who want to create social businesses of their own.

-

“There are times when Professor Yunus’ aims for Glasgow sound like something out of the Conservative’s ‘Big Society’ pitch. His latest book, Building Social Business, is 300 pages of Big Society pleading for people to go out there and create businesses which generate cash and contribute to the greater good at the same time.”Independent

-

“[A] reminder that capitalism can take kindlier forms: microfinance pioneer Yunus explains how he believes social enterprise can redeem what he regards as the failed promise of free markets.”Spectator

-

“In nine short, well-written chapters, Yunus provides genuine insight into global poverty and a unique perspective on the ways in which social businesses can coexist with traditional businesses to alleviate poverty and improve the lives of the world’s citizens.CHOICE

-

"Yunus's approach is balanced and practical. There is no sermonising or the usual 'we are from the not-for-profit sector and do gooders so we know best' approach... one cannot but marvel at Yunus's intense attempts to champion the cause of eradicating poverty. His is a case of a noted economist making a journey into the real world to face real problems and happily using his personal brand to strike tie-ups with leading multinationals to solve these problems. He needs to be read, understood; and he needs to be judged not only on his results, but on the sheer weight of his efforts. In India, good writing on the social sector is woefully inadequate. While high profile outfits such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have helped raise visibility in the sector, there is still little understanding of social business. This is an excellent read in that space."Business World (India)

-

“‘Social business is about joy,’ says Yunus. Indeed, and the book itself is joy to read. In modest prose, Yunus tells of undertakings that instill hope. He also gives a lot of ideas, along with nuts-and-bolts practical advice for people who are ready to take the plunge into the world of social business. In the years to come, it seems certain that social business will become an integral part of our economic structure and will positively change the lives of many people.”Malaysia Star

-

"Even a hard-core sceptic would find it difficult not to dream once the magic of Dr Muhammad Yunus' words as presented in the book start to make sense."Daily Star (Pakistan)

-

"Yunus may be an astute (social) businessman, but he also has a savvy side. He is quick to point out that working for any social business does not mean lowering one's standards, for they offer employees competitive salaries and benefits; it simply means not profiting from the poor...Yunus has a Nobel Peace Prize 2006 (shared with Grameen Bank) to show for his efforts, and is already playing around with the building blocks of a new poverty-free world order."Daily Times (Pakistan)

-

“Giving poor people the resources to help themselves, Dr. Yunus has offered these individuals something more valuable than a plate of food, namely security in its basic form… Dr. Yunus has invoked a new basis for capitalism whereby social business has the potential to change the failed promise of free market enterprise.”Sacramento Book Review

-

“Yunus engagingly profiles international social businesses, whether launched by multinational corporations or conceived by ordinary people with a vision to solve social problems. He offers practical advice for starting your own social businesses: from idea generation to the nuts and bolts of launching and running the concern. His impassioned dream of a different version of capitalistic endeavor is as inspirational as it is practical.”Carol J. Elsen, Univ. of Wisconsin-Whitewater, Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use