Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

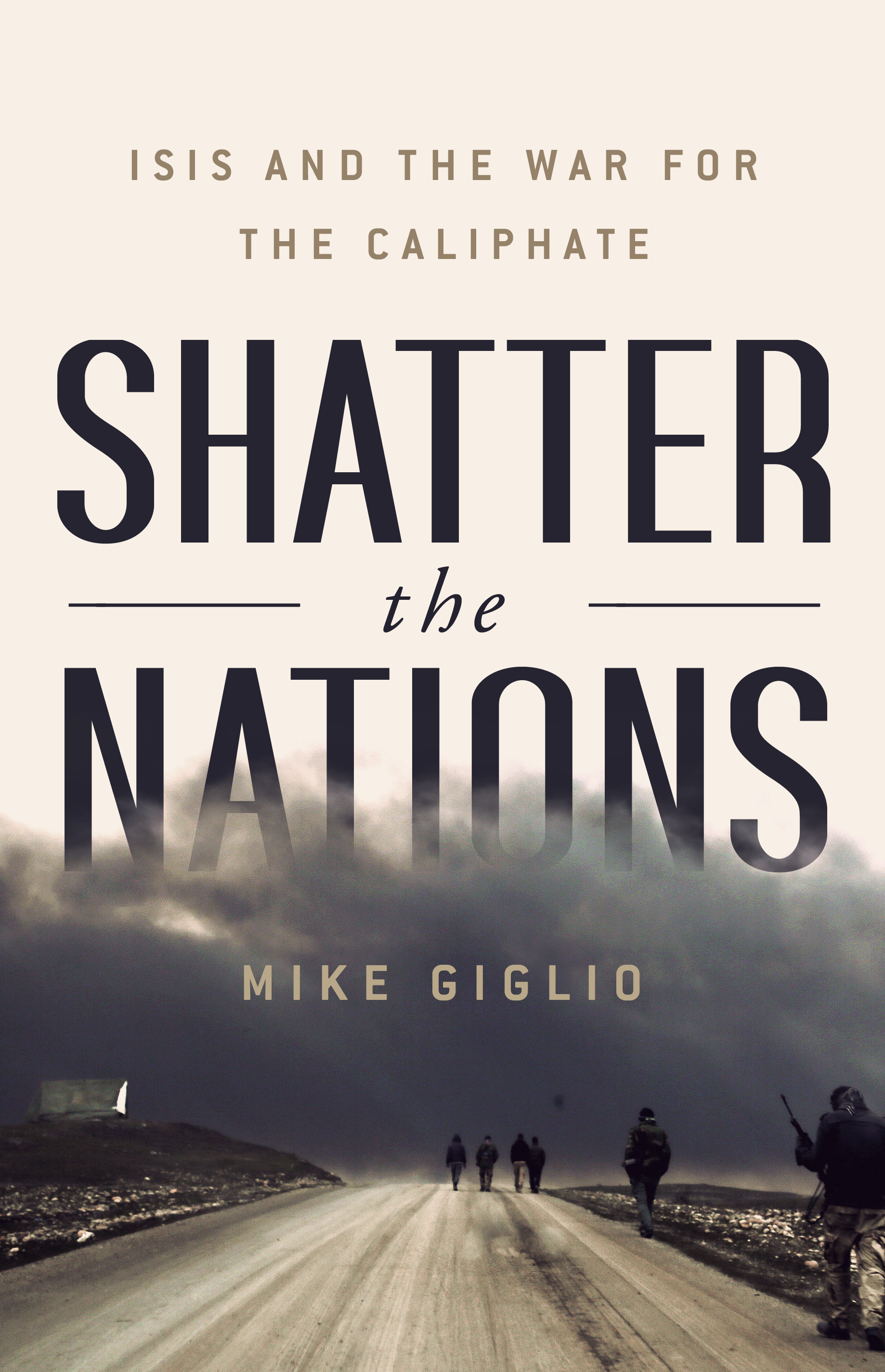

Shatter the Nations

ISIS and the War for the Caliphate

Contributors

By Mike Giglio

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742345

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Unflinching dispatches of an embedded war reporter covering ISIS and the unlikely alliance of forces who came together to defeat it.

The battle to defeat ISIS was an unremittingly brutal and dystopian struggle, a multi-sided war of gritty local commandos and militias. Mike Giglio takes readers to the heart of this shifting, uncertain conflict, capturing the essence of a modern war.

The battle to defeat ISIS was an unremittingly brutal and dystopian struggle, a multi-sided war of gritty local commandos and militias. Mike Giglio takes readers to the heart of this shifting, uncertain conflict, capturing the essence of a modern war.

At its peak, ISIS controlled a self-styled “caliphate” the size of Great Britain, with a population cast into servitude that numbered in the millions. Its territory spread across Iraq and Syria as its influence stretched throughout the wider world.

Giglio tells the story of the rise of the caliphate and the ramshackle coalition–aided by secretive Western troops and American airstrikes–that was assembled to break it down village by village, district by district. The story moves from the smugglers, traffickers, and jihadis working on the ISIS side to the victims of its zealous persecution and the local soldiers who died by the thousands to defeat it. Amid the battlefield drama, culminating in a climactic showdown in Mosul, is a dazzlingly human portrait of the destructive power of extremism, and of the tenacity and astonishing courage required to defeat it.

Genre:

-

A PBS NewsHour recommended book for 2019

-

"An open wound of a book, as raw and bleeding as the conflict itself."Rebekah Sanderlin, We Are The Mighty

-

"Beautifully written...one of the most important reflections on the war to date."Murtaza Hussain, the Intercept

-

"Giglio has written an engaging and valuable account of the battle against the Islamic State and its regional and international effects. He captures, better than most any other author, the gritty, confusing and often cynical nature of this war fought by local actors on behalf of the United States. Readers who embark with Giglio on his harrowing adventures will gain much from his eye for the details that humanize his tale."Nicholas Heras, the Washington Post

-

"An important read on the rise of the Islamic State and the West's fight to defeat the militant group, reported from the ground through beautifully captured human portraits."Lauren Katzenberg's year-end book recommendations for The New York Times At War

-

"Giglio's writing thrums with the blood pulse of battle...What powers this book more than the chilling accounts of bullets zipping through the air and bombs roaring near and far, however, are the people Giglio encounters and the stories they share. They are the beating heart of this story, and they are truly unforgettable."Peggy Kurkowski, Open Letters Review

-

"The book is like a magnet...he takes the reader along with him, into the coffeehouses and smuggling dens, the restaurants and front lines, from Turkey to Iraq and other countries."Seth Frantzman, the Jerusalem Post

-

"[A] searing debut...[Giglio's] insights into the 'strange ecosystem' of journalists, hustlers, and fixers that operate on the edges of war zones will be of interest even to readers who've had their fill of battle stories. His warning, meanwhile, that many jihadists and their families escaped ISIS territory before coalition forces moved in takes on frightening new relevance as U.S. troops withdraw from the region. Giglio's probing, prescient narrative illuminates the global repercussions of a murky conflict."Publishers Weekly

-

"An excellent and invaluable summation of the complex conflict in the Middle East from 2011-2017, shedding light on the murky circumstances behind so many political soundbites that inadequately cover terrorism and plight of refugees."Booklist

-

"Wrenching...a forthright account by an invested journalist unafraid to ask key questions about the many ramifications of the conflict."Kirkus Reviews

-

"An epic war story: bravely reported, brilliantly written, shot through with humanity."Tim Weiner, National Book Award-winning author of Legacy of Ashes

-

"Giglio's Shatter the Nations is more than a brave on-the-ground chronicle of the battle against ISIS-it is a lyrical, thrilling work that stands amongst the best of war literature."Molly Crabapple, author of Drawing Blood and illustrator of Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War

-

"With a reporter's unflinching eye and in a fine writer's clear prose, Mike Giglio has written a hypnotically compelling account of the rise and fall of the blood-drenched ISIS 'caliphate' in the Middle East. Unforgettable."Jon Lee Anderson, staff writer for the New Yorker

-

"A compelling and deeply reported narrative that explains how ISIS will have a lasting effect not just on the region but on the wider world. This is a distinguished, firsthand account that covers all sides of the conflict with the terror group--which is rare."Hassan Hassan, author of the New York Times-bestselling ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror

-

"Shatter the Nations is a reporter's account of today's Middle East wars that reads like a screenplay. Somehow Mike Giglio avoids clichés while bringing to life the suicide bombers, resistance heroes, militants, and civilians and making sense out of those murky and hideous wars."Elizabeth Becker, author of When the War Was Over

-

"Mike Giglio has done some great investigative reporting in the Middle East, but he's also the intrepid newsman ready to go to the worst place in the world. His account of the battle for Mosul, where ISIS threw everything it had at Iraqi special forces, including mortars, drone-fired grenades and suicide bomb vehicles, is hair-raising and unforgettable."Roy Gutman, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter

-

"[Giglio] beautifully unravels the rise and fall of the Islamic State...Their caliphate, and their quest to conquer, is beautifully outlined in Shatter the Nations...What makes Shatter the Nations unique is Giglio's expansive visual story line. He's a skilled reporter, but where he shines is in his storytelling. Giglio constructs a narrative following a group of unlikely characters who came together to fight for and against ISIS, and his access is enviable. He is tenacious and persistent as he moves through dangerous territory; his network would leave an intelligence officer envious (and probably did), and his information is chilling."Janine di Giovanni, AirMail