By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

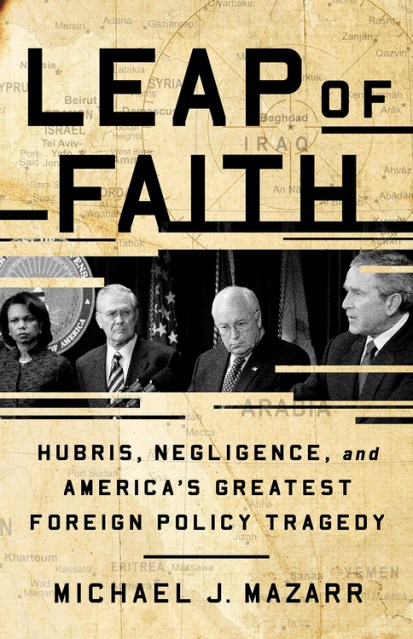

Leap of Faith

Hubris, Negligence, and America's Greatest Foreign Policy Tragedy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 19, 2019

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541768369

Price

$45.00Price

$57.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $45.00 $57.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A single disastrous choice in the wake of 9/11-the decision to use force to remove Saddam Hussein from power-did enormous damage to the wealth, well-being, and reputation of the United States. Few errors in U.S. foreign policy have had longer-lasting or more harmful consequences. Yet how the decision came to be made remains shrouded in mystery and mythology. To this day, even the principal architects of the war cannot agree on it.

Michael Mazarr has interviewed dozens of players involved in the deliberations about the invasion of Iraq and has reviewed all the documents so far declassified. He paints a devastating of portrait of an administration fueled by righteous conviction yet undercut by chaotic processes, rivalrous agencies, and competing egos. But more than the product of one bungling administration, the invasion of Iraq emerges here as a tragically typical example of modern U.S. foreign policy fiascos.

Leap of Faith asks profound questions about the limits of US power and the accountability for its use. It offers lessons urgently relevant to stave off similar disasters-today and in the future.

-

"An excellent, cleareyed study that does not look for villains but rather lessons for a possible future situation in which 'a government is in thrall to a moralistic sense of rightness.'"Kirkus, Starred Review

-

"Did the decision to invade Iraq arise from conspiracy or long-term plot, as some people suspect? No, says Michael Mazarr: the truth is actually much darker. Mazarr convincingly argues that the most costly strategic error in modern US history was the result of mistake, blunder, a toxic combination of personality traits among political and military leaders, plus intellectual and moral hubris. Leap of Faith puts the Iraq war in new light, and clarifies why and how such disasters might recur."James Fallows, national correspondent at The Atlantic and author of Blind into Baghdad and other books

-

"Leap of Faith should be mandatory reading for every US general and flag officer as well as civilian senior executives; all military officers, especially those at a US senior service college; and every graduate student at an American school of security or international studies. It will become a classic: it is this generation's Dereliction of Duty and Essence of Decision."Lieutenant General James M. Dubik, PhD, US Army, retired; author of Just War Reconsidered: Strategy, Ethics, and Theory; and former professor, Security Studies program, Georgetown University

-

"Deeply researched and written with penetrating intelligence, Leap of Faith is a remarkable new look at the run-up to the Iraq War. Breathtaking in its insights, devastating in its conclusions, Mazarr's book will stand as the definitive analysis of what went wrong and how."Jim Rasenberger, author of The Brilliant Disaster: JFK, Castro, and America's Doomed Invasion of Cuba's Bay of Pigs

-

"The Iraq War stands as one of the greatest US foreign policy blunders in history. Michael Mazarr has written the definitive account on how the decision to go to war came about. Leap of Faith contains valuable lessons for how future policy makers can avoid disaster."Ivo Daalder, president, Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and author of The Empty Throne: America's Abdication of Global Leadership

-

"Mazzar has written an excellent antidote to the simplistic and wrong Iraq narrative that 'Bush lied, people died.' He shows how US leaders tried to confront all potential threats after 9/11, and he describes the mistakes that led Iraq from the tragedy of Saddam to the tragedy of chaos. He writes wonderfully and shows very well the dilemmas facing successive generations of leaders of what is indeed 'the indispensable nation.'"William Shawcross, author of Allies: Why the West Had to Remove Saddam

-

"Michael Mazarr's Leap of Faith is an incisive inquest into America's most disastrous war since Vietnam. Written with panache and precision, Mazarr illustrates that the war was made possible by a strain of missionary zeal that lives on. . . . A seminal, sharp and prophetic history. We have been warned."Patrick Porter, chair in international security and strategy, University of Birmingham, and author of Blunder: Britain's War in Iraq

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use