Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

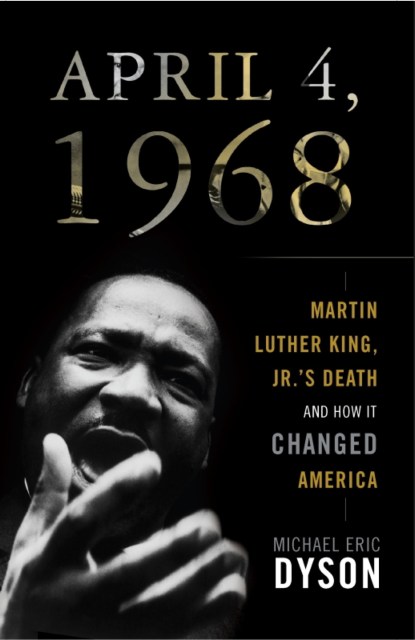

April 4, 1968

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Death and How It Changed America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 6, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465012558

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.50 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 6, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Acclaimed public intellectual and best-selling author Michael Eric Dyson uses the fortieth anniversary of King’s assassination as the occasion for a provocative and fresh examination of how King fought, and faced, his own death, and we should use his death and legacy. Dyson also uses this landmark anniversary as the starting point for a comprehensive reevaluation of the fate of Black America over the four decades that followed King’s death. Dyson ambitiously investigates the ways in which African-Americans have in fact made it to the Promised Land of which King spoke, while shining a bright light on the ways in which the nation has faltered in the quest for racial justice. He also probes the virtues and flaws of charismatic black leadership that has followed in King’s wake, from Jesse Jackson to Barack Obama.

Always engaging and inspiring, April 4, 1968 celebrates the prophetic leadership of Dr. King, and challenges America to renew its commitment to his deeply moral vision.