By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

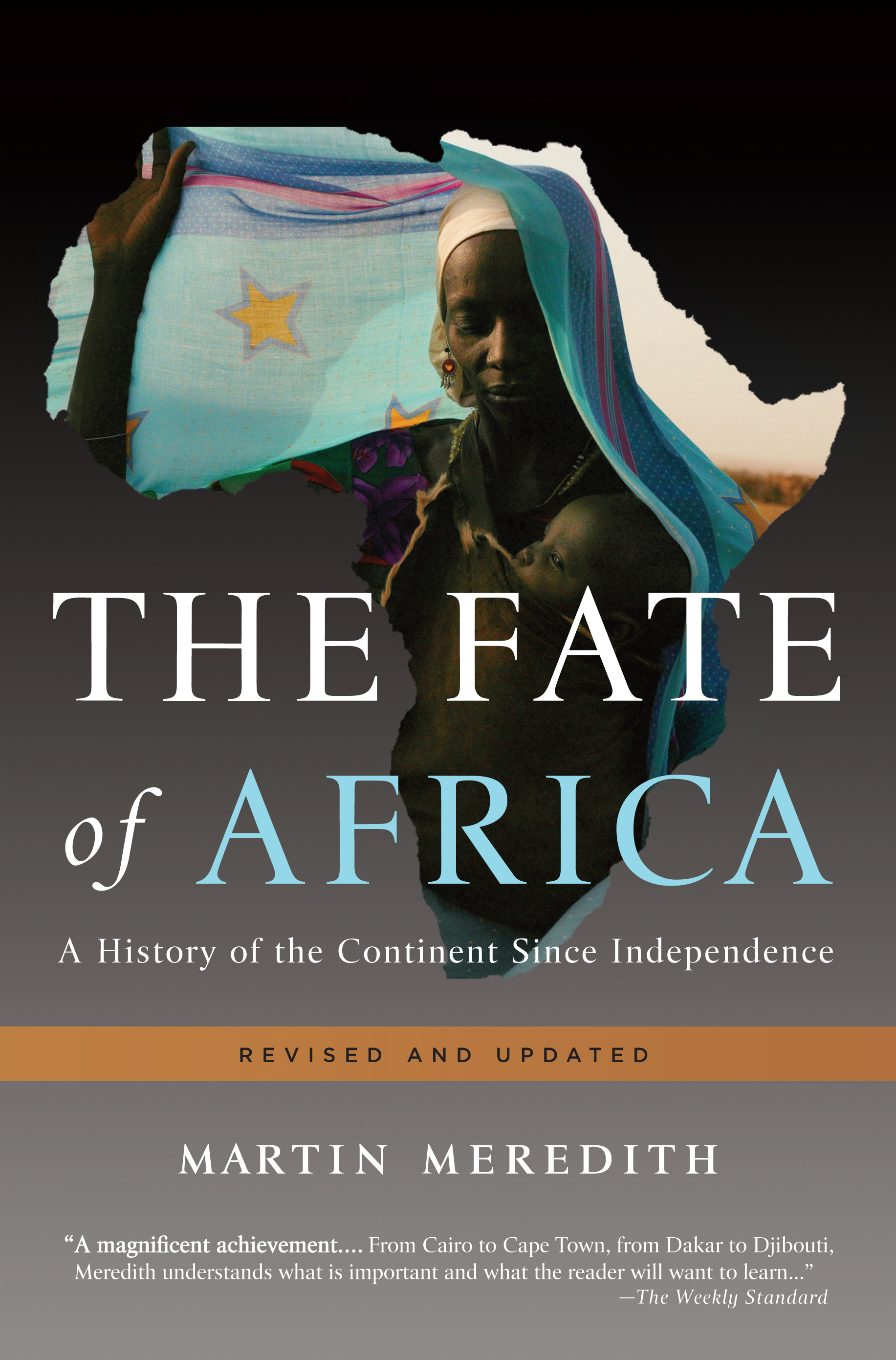

The Fate of Africa

A History of the Continent Since Independence

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 6, 2011

- Page Count

- 816 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391320

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 6, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Fate of Africa has been hailed by reviewers as “A masterpiece….The nonfiction book of the year” (The New York Post); “a magnificent achievement” (Weekly Standard); “a joy,” (Wall Street Journal) and “one of the decade’s most important works on Africa” (Publishers Weekly, starred review). Spanning the full breadth of the continent, from the bloody revolt in Algiers against the French to Zimbabwe’s civil war, Martin Meredith’s classic history focuses on the key personalities, events and themes of the independence era, and explains the myriad problems that Africa has faced in the past half-century. It covers recent events like the ongoing conflict in Sudan, the controversy over Western aid, the exploitation of Africa’s resources, and the growing importance and influence of China.

Genre:

-

"Though today an independent scholar, Meredith was one of those now-too-rare journalists who knew his beat intimately, having lived on and off (mostly on) in Africa for 40 years, informing a keen and humane mind with all things African. It shows here in the depth and fluid familiarity of his narrative, light on its feet for so wildly complex a picture. Meredith isn't afraid of venturing an opinion, but what he dines on are basic realities: who did what when, and the consequences. These he spreads before his readers, for them to draw their own, now also informed, conclusions."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"For the author, even organizing this information is a hugely daunting job. How can such vast amounts of information be analyzed for the reader? One way was to follow parallel developments in different places-which is more or less how Mr. Meredith works, with attention to the hair-trigger ways in which one coup or crisis could set off subsequent disasters. He is able to steer the book firmly without compromising its hard-won clarity."New York Times

-

"The Fate of Africa is a comprehensive, wonderfully readable survey of the entire continent's recent past. . . . Blessed with a strong, clean prose style, the author has delivered a work that offers an education in one volume and, despite its length, the book maintains the pace of an artful novel. . . ."New York Post

-

"Meredith first traveled up the Nile from Cairo in 1964 as a 21-year-old and claims that, in many ways, his 'African journey has continued ever since.' His careful, detailed analysis, his dispassionate but not detached writing, and his evident wit mean that we might all hope his journey continues for much longer."Weekly Standard

-

"Meredith's exhaustive study appears just as world leaders are finally trying to come to grips with Africa's needs. It starkly underlines the urgency of that task."Providence Journal

-

"In this book [Meredith] provides the most comprehensive description of the causes and consequences of failure in quite a while."Boston Globe

-

"The book is elegantly written as well as unerringly accurate, and despite its considerable length it holds the attention of the reader to the end."Financial Times

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use