By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

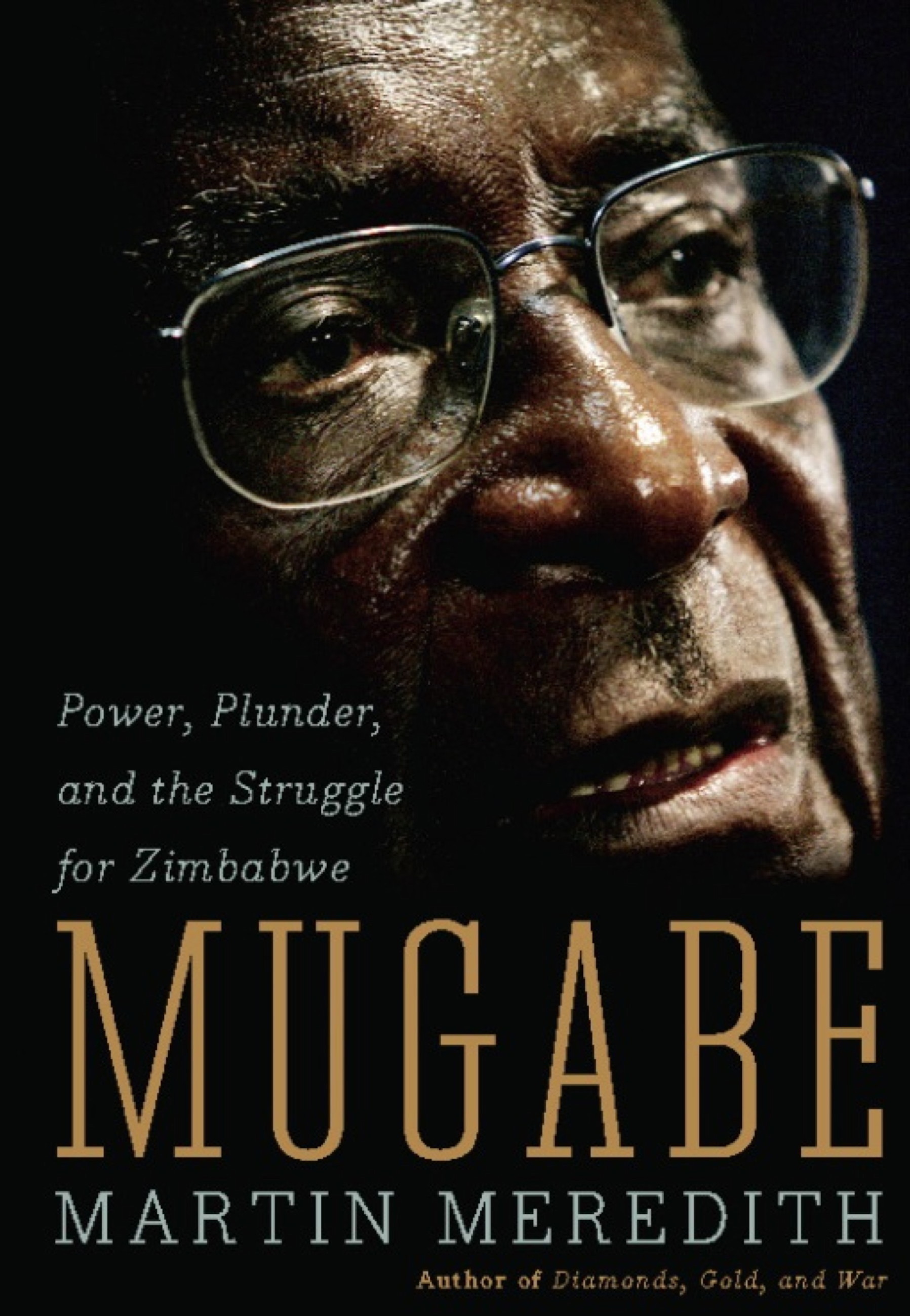

Mugabe

Power, Plunder, and the Struggle for Zimbabwe's Future

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 28, 2009

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786732937

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 28, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Robert Mugabe came to power in Zimbabwe in 1980 after a long civil war in Rhodesia. The white minority government had become an international outcast in refusing to give in to the inevitability of black majority rule. Finally the defiant white prime minister Ian Smith was forced to step down and Mugabe was elected president. Initially he promised reconciliation between white and blacks, encouraged Zimbabwe’s economic and social development, and was admired throughout the world as one of the leaders of the emerging nations and as a model for a transition from colonial leadership. But as Martin Meredith shows in this history of Mugabe’s rule, Mugabe from the beginning was sacrificing his purported ideals—and Zimbabwe’s potential—to the goal of extending and cementing his autocratic leadership. Over time, Mugabe has become ever more dictatorial, and seemingly less and less interested in the welfare of his people, treating Zimbabwe’s wealth and resources as spoils of war for his inner circle. In recent years he has unleashed a reign of terror and corruption in his country. Like the Congo, Angola, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Liberia, Zimbabwe has been on a steady slide to disaster. Now for the first time the whole story is told in detail by an expert. It is a riveting and tragic political story, a morality tale, and an essential text for understanding today’s Africa.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use