Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

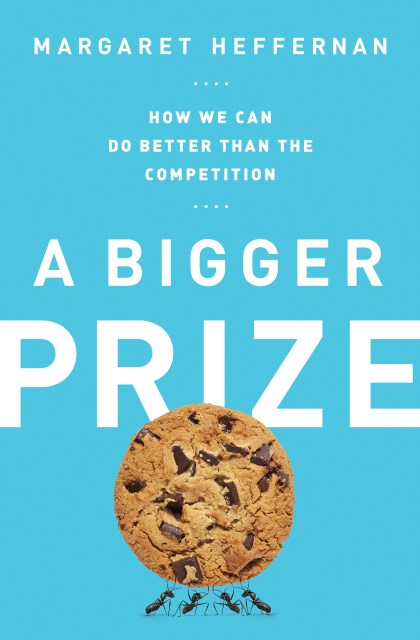

A Bigger Prize

How We Can Do Better than the Competition

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 8, 2014

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610392914

Price

$27.99Format

Format:

- Hardcover $27.99

- ebook $15.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 8, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Get into the best schools. Land your next big promotion. Dress for success. Run faster. Play tougher. Work harder. Keep score. And whatever you do — make sure you win.

Competition runs through every aspect of our lives today. From the cubicle to the race track, in business and love, religion and science, what matters now is to be the biggest, fastest, meanest, toughest, richest.

The upshot of all these contests? As Margaret Heffernan shows in this eye-opening book, competition regularly backfires, producing an explosion of cheating, corruption, inequality, and risk. The demolition derby of modern life has damaged our ability to work together.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. CEOs, scientists, engineers, investors, and inventors around the world are pioneering better ways to create great products, build enduring businesses, and grow relationships. Their secret? Generosity. Trust. Time. Theater. From the cranberry bogs of Massachusetts to the classrooms of Singapore and Finland, from tiny start-ups to global engineering firms and beloved American organizations — like Ocean Spray, Eileen Fisher, Gore, and Boston Scientific — Heffernan discovers ways of living and working that foster creativity, spark innovation, reinforce our social fabric, and feel so much better than winning.

-

“Heffernan systematically deconstructs the social myths associated with hypercompetitiveness while providing a formidable case about how counterproductive, and even perverse, it can be…[She] considers the effects of hypercompetitiveness in the realms of family, education, sports, scientific research, and business and corporate leadership….The step-by-step accumulation of argument and evidence is overwhelming in its thoroughness and attention to detail.”—Kirkus, STARRED review

"In this bold sociology of organizations, Heffernan sets her sights on an issue that cuts across industries, nations, and individuals: Why is our obsession with winning not only failing to deliver the benefits we expect, but leaving us ill equipped to solve the problems competition creates?..."A Bigger Prize" is an important call to build more collaborative, trustworthy and enduring institutions." —New York Times Book Review