By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

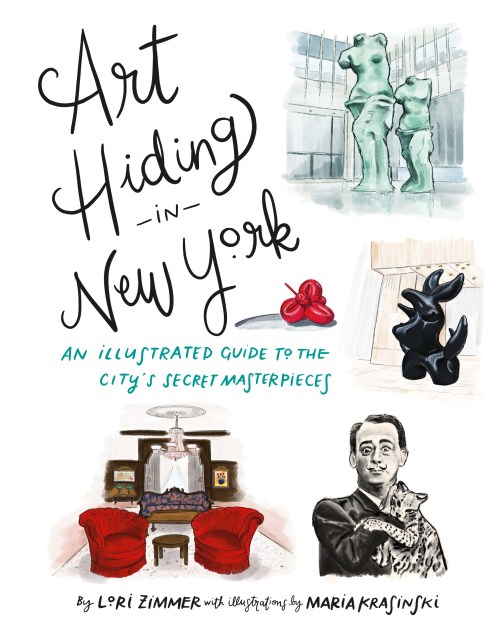

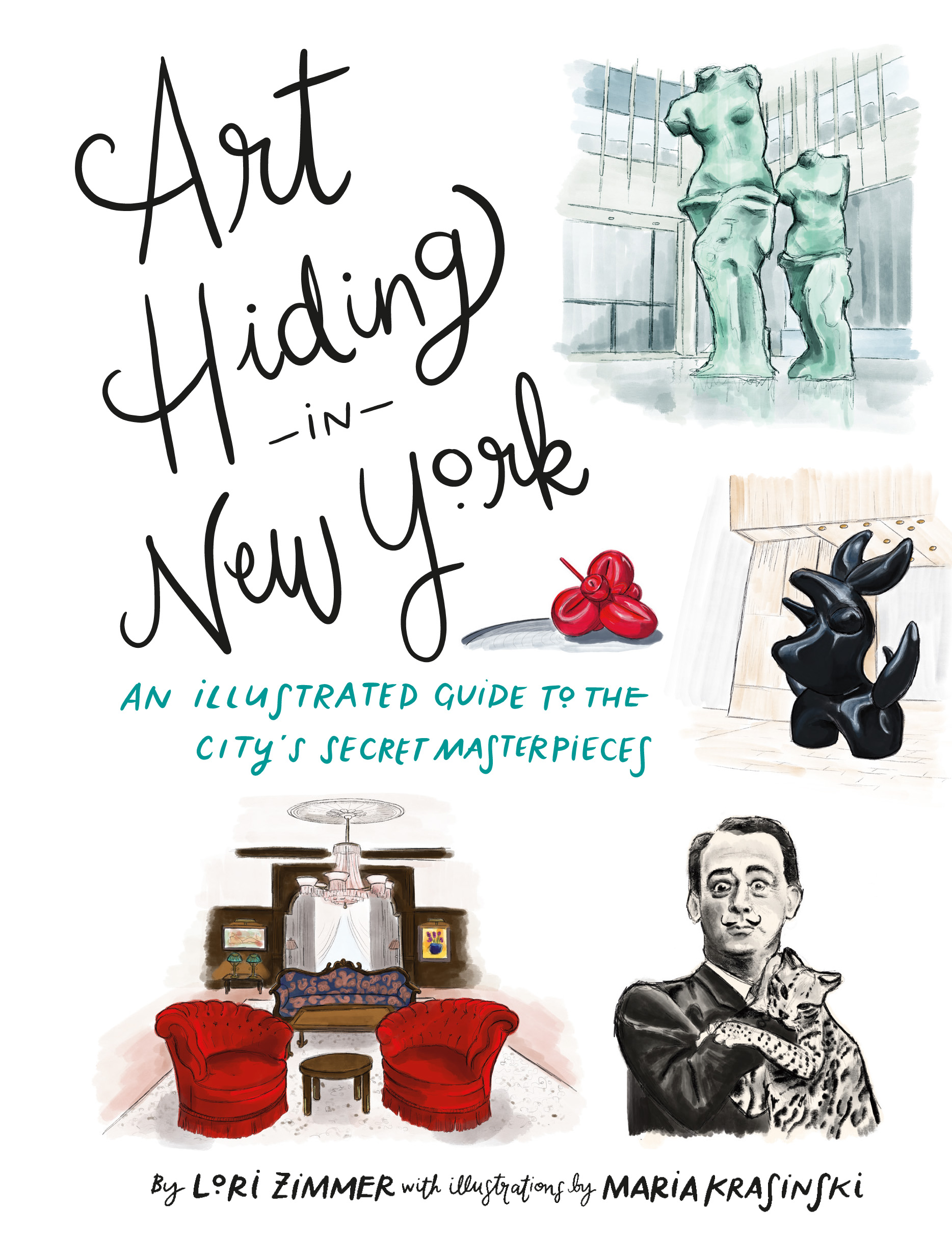

Art Hiding in New York

An Illustrated Guide to the City's Secret Masterpieces

Contributors

By Lori Zimmer

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2020

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762471010

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.00 $33.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

There's so much to love about New York, and so much to see. The city is full of art, and architecture, and history — and not just in museums. Hidden in plain sight, in office building lobbies, on street corners, and tucked into Soho lofts, there's a treasure trove of art waiting to be discovered, and you don't need an art history degree to fall in love with it.

Art Hiding in New York is a beautiful, giftable book that explores all of these locations, traversing Manhattan to bring 100 treasures to art lovers and intrepid New York adventurers. Curator and urban explorer Lori Zimmer brings readers along to sites covering the biggest names of the 20th century — like Jean-Michel Basquiat's studio, iconic Keith Haring murals, the controversial site of Richard Serra's Tilted Arc, Roy Lichtenstein's subway station commission, and many more. Each entry is accompanied by a beautiful watercolor depiction of the work by artist Maria Krasinski, as well as location information for those itching to see for themselves. With stunning details, perfect for displaying on any art lover's shelf, and curated itineraries for planning your next urban exploration, this inspirational book is a must-read for those who love art, New York, and, of course, both.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use