Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

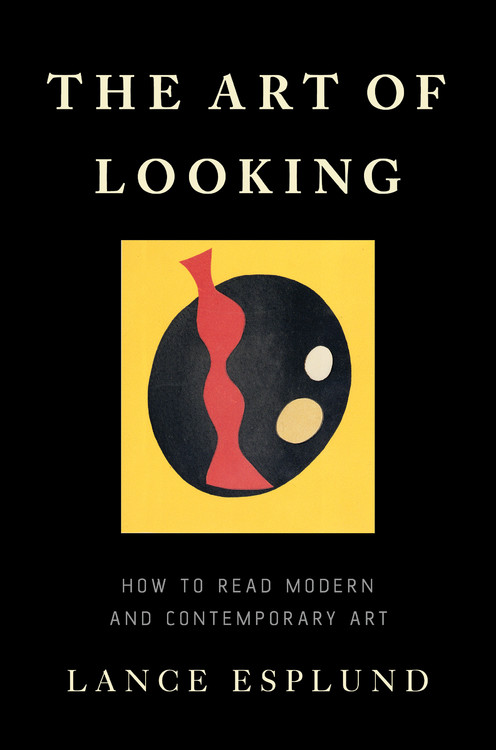

The Art of Looking

How to Read Modern and Contemporary Art

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 27, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465094660

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 27, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The landscape of contemporary art has changed dramatically during the last hundred years: from Malevich’s 1915 painting of a single black square and Duchamp’s 1917 signed porcelain urinal to Jackson Pollock’s midcentury “drip” paintings; Chris Burden’s “Shoot” (1971), in which the artist was voluntarily shot in the arm with a rifle; Urs Fischer’s “You” (2007), a giant hole dug in the floor of a New York gallery; and the conceptual and performance art of today’s Ai Weiwei and Marina Abramovic. The shifts have left the art-viewing public (understandably) perplexed.

In The Art of Looking, renowned art critic Lance Esplund demonstrates that works of modern and contemporary art are not as indecipherable as they might seem. With patience, insight, and wit, Esplund guides us through the last century of art and empowers us to approach and appreciate it with new eyes. Eager to democratize genres that can feel inaccessible, Esplund encourages viewers to trust their own taste, guts, and common sense. The Art of Looking will open the eyes of viewers who think that recent art is obtuse, nonsensical, and irrelevant, as well as the eyes of those who believe that the art of the past has nothing to say to our present.

Genre:

-

"[A] wise, wonderful new book...Life is busy and art is demanding, but reading Esplund prods us to take the aesthetic plunge, to commit to a James Turrell light sculpture or a forbiddingly monumental Richard Serra art space the same way we do to a Rembrandt, a Berthe Morisot, a Picasso."Washington Post

-

"Encouraging, intelligent, and thought-provoking."New York Journal of Books

-

"Everybody who cares about the art of our time will want to own this brilliant book. Lance Esplund brings ease, elegance, and incisiveness to his passionate encounters with creative spirits old and new. His essential belief, presented in prose by turns tough-minded and tenderhearted, is that contemporary practice must be grounded in timeless, universal values. The Art of Looking shines a strong and steady light. We need it."Jed Perl, author of Calder: The Conquest of Time and New Art City: Manhattan at Mid-Century

-

"Esplund's conversational new book aims to coach its readers through the slow process and at-times-difficult experience of seeing...[He] is at his best when he is able to reach to the past, and to the timeless traditions and values that all successful art shares in."New Criterion

-

"This important, unconventional book begins as a terrific first-aid manual, highly accessible and full of great common sense, for those for whom modern or contemporary art is puzzling or off-putting. It evolves into a dazzling, jargon-free display of the exercise of slow, close, curious looking at all kinds of art. Those seeking relief from the plague of art-speak will find it in this insightful, unashamedly personal volume."John Elderfield, chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture, the Museum of Modern Art

-

"In a friendly and conversational tone, Esplund shares his insights honed during a long career...Inviting and informative."Kirkus

-

Presenting itself as an introductory volume to help orient beginners, The Art of Looking opens with a brisk, illuminating historical sweep before zooming in on specific works by ten dissimilar artists spanning nearly a century. An intensive exercise in meticulous observation and close reading, the book offers a personal overview that should interest art-world sophisticates as well as newcomers to the field.Elizabeth C. Baker, editor-at-large, Art in America

-

"The Art of Looking is a wonderful book, filled with remarkable insights about experiencing whatever it is that we mean by the word 'art.' Whether it is Balthus and the Me Too Movement or walking through Richard Serra's enormous curving rust colored sculptures -- there is always something new and exciting to be discovered."Robert Benton

-

"If you've never understood contemporary art, or fear you've understood it all too well, then this book is ready to be your secret friend. In lucid prose that has the loft of poetry, Lance Esplund lifts the burden of 'art appreciation' to reveal that the subject of all great art is how it appreciates you for the way you look at it. His own encounters with exemplary work-by Joan Mitchell, James Turrell, and Marina Abramovic among others-are related in terms so complete, courageous, and physically convincing they make you want to see art as he has seen it, a giant step toward seeing it for oneself."Douglas Crase, author of The Revisionist

-

"Despite dramatic shifts in art over the last century, [Lance Esplund] empowers and enables us to appreciate it with 'new eyes.' Rather than perceiving new art as inaccessible or irrelevant, Esplund gently encourages us to trust our own tastes, feelings and opinions."Detroit Free Press

-

"[Esplund] guides us through art made in the last century and how we can approach it in a way that's accessible and rewarding."My Modern Met

-

"Avoiding the exclusionary vocabularies that abound in the art world, Esplund's new book conversationally guides the interested newcomer towards confidence in approaching western contemporary art...Esplund believes art should actively stir, not passively amuse."Aesthetica