By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

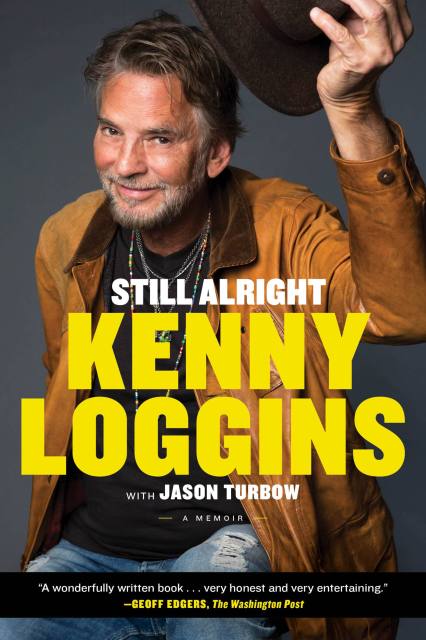

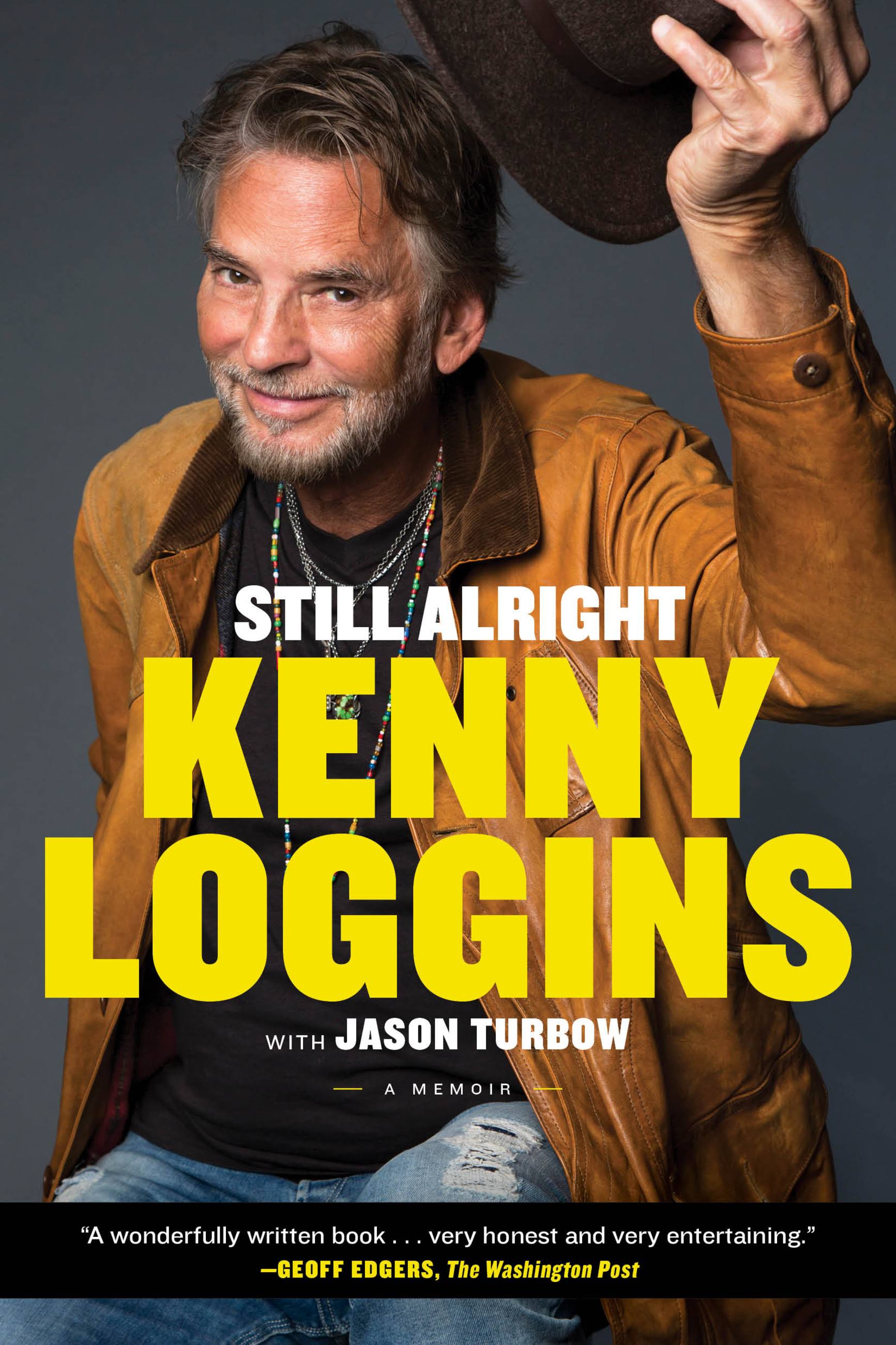

Still Alright

A Memoir

Contributors

With Jason Turbow

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 13, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306925382

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 13, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Enjoy the stories behind Kenny Loggins’ legendary five-decade career as a celebrated songwriter, chart-topping collaborator, and “The Soundtrack King” with this pop icon’s intimate and entertaining music memoir.

In a remarkable career, Kenny Loggins has rocked stages worldwide, released ten platinum albums, and landed hits all over the Billboard charts. His place in music history is marked by a unique gift for collaboration combined with the vision to evolve, adapt, and persevere in an industry that loves to eat its own. Loggins served as a pivotal figure in the folk-rock movement of the early ’70s when he paired with former Buffalo Springfield member Jim Messina, recruited Stevie Nicks for the classic duet “Whenever I Call You ‘Friend,’” then pivoted to smooth rock in teaming up with Michael McDonald on their back-to-back Grammy-winning hits “What a Fool Believes” and “This Is It” (a seminal moment in the history of what would come to be known as yacht rock). In the ’80s, Loggins became the king of soundtracks with hit recordings for Caddyshack, Footloose, and Top Gun; and a bona fide global superstar singing alongside Bruce Springsteen and Michael Jackson on “We Are the World.”In Still Alright, Kenny Loggins gives fans a candid and entertaining perspective on his life and career as one of the most noteworthy musicians of the 1970s and ’80s. He provides an abundance of compelling, insightful, and terrifically amusing behind-the-scenes tales. Loggins draws readers back to the musical eras they’ve loved, as well as addressing the challenges and obstacles of his life and work—including two marriages that ended in divorce, a difficult but motivating relationship with the older brother for which “Danny’s Song” is named, struggles with his addiction to benzodiazepines, and the revelations of turning seventy and looking back at everything that has shaped his music—and coming to terms with his rock-star persona and his true self.

-

“A wonderfully written book…very honest and very entertaining.”Geoff Edgers, The Washington Post

-

“A page-turning memoir…The book is an honest, straightforward account of [Loggins’] rock n’roll career.”Margaret Hoover, PBS’ The Firing Line

-

"Highly entertaining."Spin

-

“A good beach read for the yacht-rock generation.”Kirkus Reviews

-

"Legendary songwriter Loggins brings the energy of his live performances to the page in this exhilarating look at his career.... Loggins’ frank reflections on his craft are what beg an encore.... Fans won’t want to skip this one."Publishers Weekly

-

“Still Alright seems almost perfectly balanced in that includes plenty of words of all three legs of a good Rock Memoir Stool: creative/recording process, personal revelations/insight, and stories/anecdotes.”HoustonPress

-

“Loggins’ thoughtful reflections on the process of songwriting turn this memoir into more than a run-of-the-mill rocker’s reflections on a life of sex, drugs, and, oh yeah, rock and roll. Songwriting occupies the center of Loggins’ narrative…His appealing memoir celebrates him home in fine form.”No Depression

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use