Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

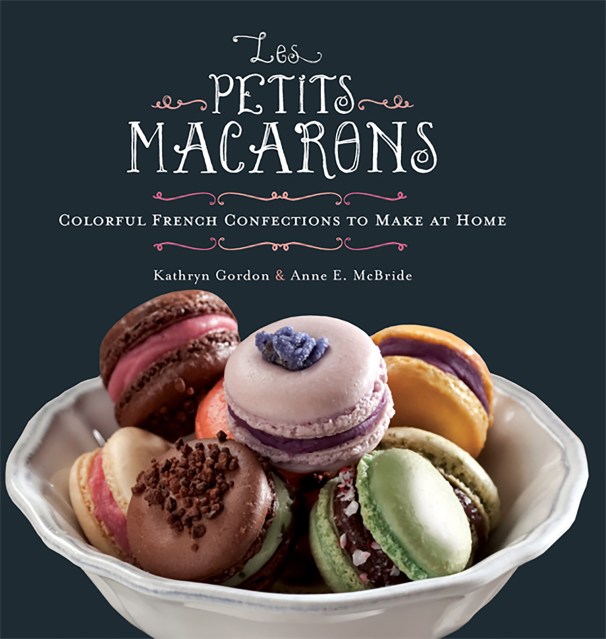

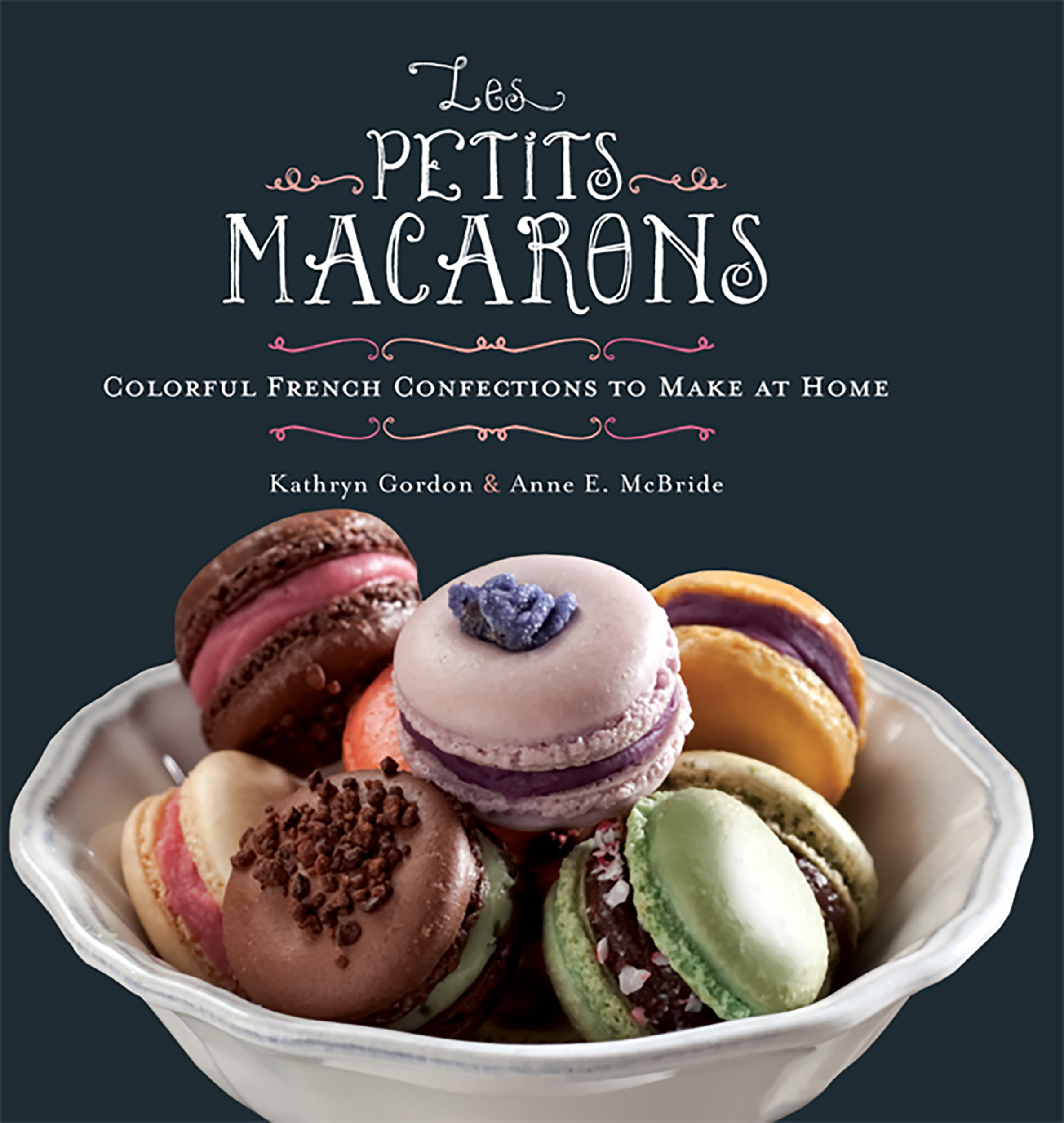

Les Petits Macarons

Colorful French Confections to Make at Home

Contributors

By Anne E. McBride

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $14.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Macarons have become a worldwide sensation, whether it be because of their dazzling assortment of colors, their associations with Parisian elegance, or just because they taste amazing! These delectable little delights may seem daunting for any home baker, but authors Kathryn Gordon and Anne E. McBride are here to demystify macarons.

This book is like a private baking class in your very own kitchen, with careful, detailed instruction and recipes guaranteed to bring the flavors of France right to your door. It features dozens of flavor combinations, structured around three basic shell methods-French, Swiss, and Italian-with a never-before-seen Easiest French Macaron Method (and a convenient Troubleshooting Guide) that is sure to make macaron magic possible for anyone using nothing more than a mixer, an oven, and a piping bag.

Shell flavors include:

- Pistachio

- Blackberry

- Coconut

- Red velvet

- Crunchy dark chocolate ganache

- Lemon curd

- Strawberry guava pate de fruit

There are even savory flavors like saffron, parsley, and ancho chile paired with fillings like hummus, foie gras with black currant, or duck confit with port and fig. Les Petits Macarons offers endless possibilities for everyone to enjoy!

Genre:

-

"Kathryn and Anne have put together a great collection of Parisian macarons, today's top must-have sweet indulgence."Nick Malgieri, author of Bake! and The Modern Baker

-

"I thought I had to go to Paris to find these luscious confections, but now I have them in my own kitchen. Thank you Kathryn and Anne for sharing the technique and demystifying the method! With these detailed recipes and clear explanations, we can all create dazzling French macarons in every imaginable flavor. A must for serious bakers."Susan G. Purdy, author of Pie in the Sky, Family Baker, and Have Your Cake & Eat it, Too

-

"This is a wonderful book on a on a mouth watering delicacy - macrons. I am amazed, impressed and educated with your contribution, research, diversity and skills. I enjoyed the simplicity and the depth of information in the book. Well done Kathryn."Anil Rohira, World Pastry Champion

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2011

- Page Count

- 228 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762443635

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use