By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

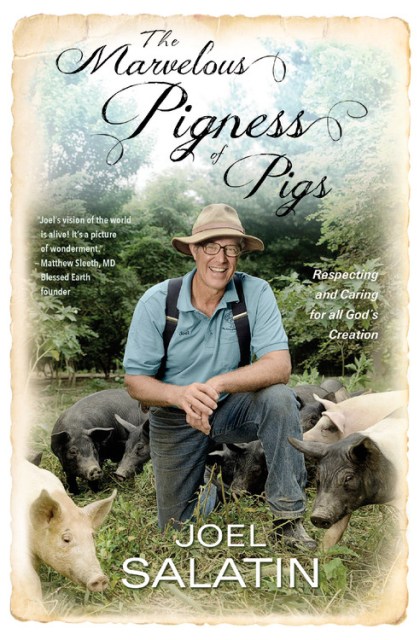

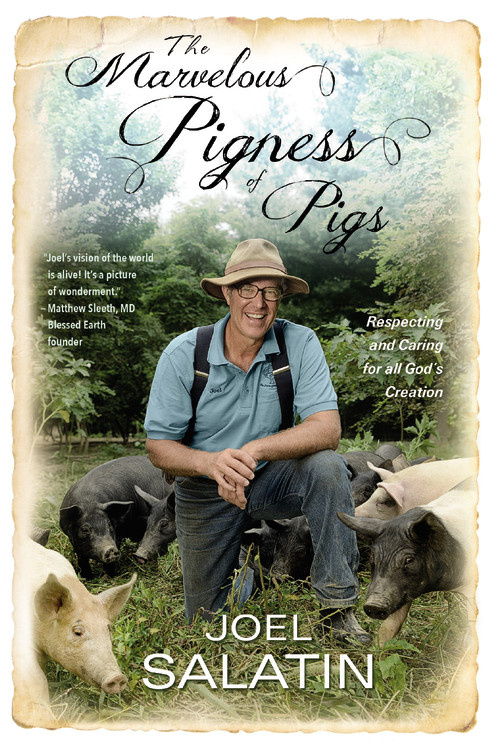

The Marvelous Pigness of Pigs

Respecting and Caring for All God's Creation

Contributors

By Joel Salatin

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 30, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- FaithWords

- ISBN-13

- 9781455536986

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What on earth is The Marvelous Pigness of Pigs? It’s an inspiring call to action for people of faith . . . a heartfelt plea to heed the Bible’s guidance . . . .

It’s an important and thought-provoking explanation of how by simply appreciating the marvelous pigness of pigs, we are celebrating the Glory of God.

As a man of deep faith and student of the Bible, and as a respected and successful ecological family farmer, Joel Salatin knows that God created heaven and earth and meant for all living organisms to be true to their nature and their endowed holy purpose. He intended for us to respect and care for His gift of creation, not to ravage and mistreat it for our own pleasure or wealth.

The example that inspires the book’s title explains what Salatin means: when huge corporate farms confine pigs in cramped and dark pens, inject them with antibiotics and feed them herbicide-saturated food simply to increase profits, they are not respecting them as a creation of God or allowing them to express even their most rudimentary uniqueness – that special role that is part of His design. Every living organism has a God-given uniqueness to its life that must be honored and respected, and too often that is not happening today.

Salatin shows us the long overlooked ethics and instructions in the Bible for how to eat, how to shop, how to think about how we farm and feed the world. Through scripture and Biblical stories, he shows us why it’s more vital than ever to look to the good book rather than corporate America when feeding the country and your family.

Salatin makes a compelling case for Christian stewardship of the earth and how it relates to every action we take regarding our food. He also opens our eyes to a common misconception many Christians may have about environmentalism: it’s not a bad thing, and definitely not just the province of secular liberals; it’s really a very good thing, part of heeding God’s Word.

With warmth and with humor, but with no less piercing criticism of the industrial food complex, Salatin brings readers on a fascinating journey of farming, food and faith. Readers will not say grace over their plates the same way ever again.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use