By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

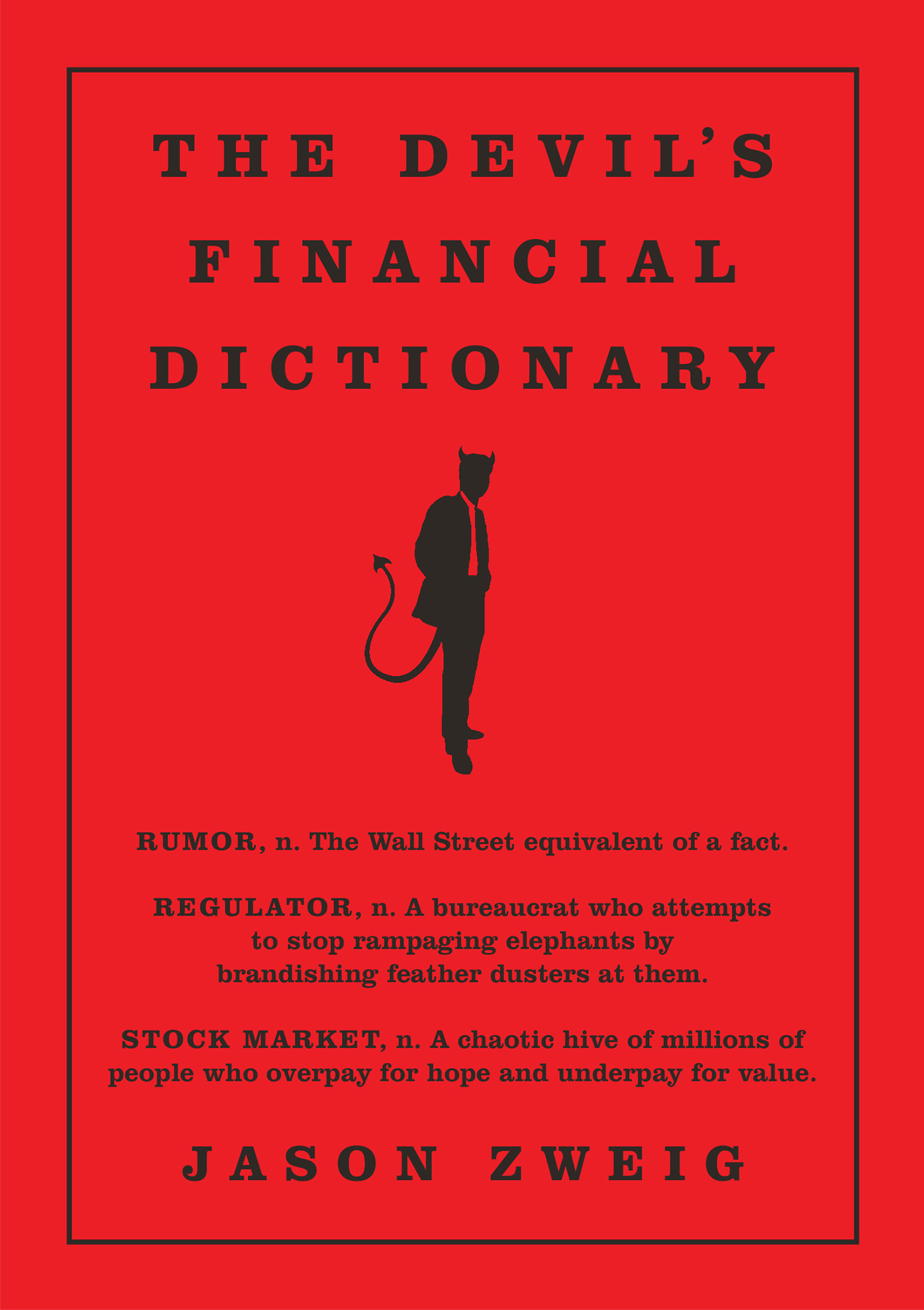

The Devil’s Financial Dictionary

Contributors

By Jason Zweig

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2015

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396066

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Devil’s Financial Dictionary skewers the plutocrats and bureaucrats who gave us exploding mortgages, freakish risks, and banks too big to fail. And it distills the complexities, absurdities, and pomposities of Wall Street into plain truths and aphorisms anyone can understand.

An indispensable survival guide to the hostile wilderness of today’s financial markets, The Devil’s Financial Dictionary delivers practical insights with a scorpion’s sting. It cuts through the fads and fakery of Wall Street and clears a safe path for investors between euphoria and despair.

Staying out of financial purgatory has never been this fun.

-

“Jason Zweig has long been a brilliant financial journalist. People who have listened to Jason have shielded their assets from the purveyors of costly and useless advice. In The Devil?s Financial Dictionary, Jason turns his wit and insight to arming us with an understanding of the financial terms that too many professionals use to intentionally baffle investors.” —Max H. Bazerman, co-director, the Center for Public Leadership, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University; author of The Power of Noticing

“Jason Zweig, one of the great truth-tellers in financial journalism, is the spiritual heir to Ambrose Bierce, one of the great satirists in American letters. Both use piercing wit to reveal important truths.” —Gary Belsky, coauthor of Why Smart People Make Big Money Mistakes and How to Correct Them

"Broad experience, thorough conversance with history, unusual insight, and dashes of humor and cynicism. This is what you need to understand the world of investing, and this is what you?ll find in The Devil?s Financial Dictionary by Jason Zweig." —Howard Marks, Co-Chairman, Oaktree Capital Management, L.P.; author, The Most Important Thing: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor -

“Someone had to write a short, punchy book on the fibs and fables of Wall Street during this second Gilded Age for the extravagantly-paid manipulators of our financial system. Happily for readers—whether wise, naïve, or victimized—journalist Jason Zweig picked up the challenge, and ran for the winning touchdown with it. Laugh, cry, and learn as you enjoy the sparkling Devil?s Financial Dictionary.” —John C. Bogle, founder of The Vanguard Group; author of Common Sense on Mutual Funds

“A delightfully humorous and stunningly irreverent Ambrose Bierce for financial markets. This satirical critique of what passes for wisdom on Wall Street belongs on the bookshelf of every serious investor.” —Burton G. Malkiel, professor of finance emeritus, Princeton University; author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street

“Open this wonderful book to any page. Try not to laugh. I dare you.” —James Grant, Grant?s Interest Rate Observer

“Jason Zweig?s book is absolutely marvelous. It combines wicked humor, scholarly etymology, and superb advice. If you have money invested, you must read this book; if you don?t, read it anyway for pure fun.” —William F. Sharpe, emeritus professor of finance, Stanford University; Nobel laureate in economics -

“Wall Street frequently uses complex terminology to keep its own customers in the dark. That is why Jason Zweig?s The Devil?s Financial Dictionary is so refreshing. Zweig, who has a lifetime of experience covering finance, exposes the language of Wall Street with sharp wit, historical perspective, and a skeptic?s eye.” —Tadas Viskanta, founder and editor, Abnormal Returns, and author of Abnormal Returns: Winning Strategies from the Frontlines of the Investment Blogosphere

“THE DEVIL?S FINANCIAL DICTIONARY, n. A compendium of financial jargon observed to induce in its readers nearly continuous spasms of raucous laughter. Has also been known to produce near-fatal episodes of cognitive dissonance in brokers, advisors, and money managers, who should consume its contents with care. Normal individuals, in contrast, may incur a deepening of financial wisdom, a fattening of the wallet, and an uncontrollable urge to steal entire passages for later use.” —William J. Bernstein, author of The Four Pillars of Investing</i. and A Splendid Exchange

“If finance were stand-up comedy, Jason Zweig would be its Groucho Marx—a serious man with a wild sense of humor: `Dog: A stock that obeys no command except DOWN?…need I say more?” —Laurence B. Siegel, research director, CFA Institute Research Foundation -

“You?ll love this book. Zweig cuts through financial hypocrisy to expose Wall Street?s cynical core, and does it hilariously. You?ll also get some super-smart investment tips. One of my favorite devilish definitions: `Broker: Buys and sells stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other assets for people who are under the delusion that the broker is doing something other than guesswork.?” —Jane Bryant Quinn, author of Making the Most of Your Money Now

“Both witty and wise—with just a refreshing dash of cynicism—The Devil?s Financial Dictionary should be on every desk on both Wall Street and Main Street.” —John Steele Gordon, author of An Empire of Wealth and The Business of America

"Vintage Jason Zweig: entertaining, truthful and oh so telling about Wall Street. The definition of Day Trader -' n. See IDIOT' - says it all. Any investor who does not read this witty, insightful and rueful reminder of Wall Street?s financial follies is an IDIOT!” —Consuelo Mack, anchor and executive producer, Consuelo Mack WealthTrack -

"'Witty' and 'fun' are two adjectives that may never have been used to describe a dictionary, but they apply to this one. But it is not just jokes; I learned a lot browsing around in this clever little book.” —Richard H. Thaler, professor of behavioral science and economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business; author of Misbehaving and co-author of Nudge

"Cynical and exceptionally witty, this book shines a light into the unlit corners of finance. After a lot of laughs, I walked away with a less distorted view of reality." —Shane Parrish, CEO of Farnam Street Media

"Jason Zweig is a journalist known for his wise investment counsel. But he also has a wicked wit, which is on full display in The Devil's Financial Dictionary. A fun romp for those who don't take themselves too seriously." —Michael J. Mauboussin, head of global financial strategies, Credit Suisse; author of The Success Equation and Think Twice

“Fun, interesting, irreverent, and well-informed, Jason Zweig scores again. You?ll laugh and cry—and send copies to your friends.” —Charles D. Ellis, founder, Greenwich Associates; author of Winning the Loser?s Game: Timeless Strategies for Successful Investing -

“The Devil's Financial Dictionary is witty, irreverent, skeptical and humorous—making it an entertaining read for those within and outside the financial industry.” —Manhattan Book Review

”Consistently yields pleasure and insight…. Thanks to the author?s staggering command of his subject, readers of this book will shed costly misconceptions and acquire wisdom that, if accompanied by patience, could pay off richly. The serious message embedded in the book?s humor is that investors who pay attention to stock market lore and Wall Street hype are their own worst enemies in securing their financial future.” —BARRONS

“This is the most amusing presentation of the principles of finance that I have ever seen.” —Robert J. Shiller, professor of finance, Yale University; Nobel laureate in economics; author of Irrational Exuberance

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use