By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

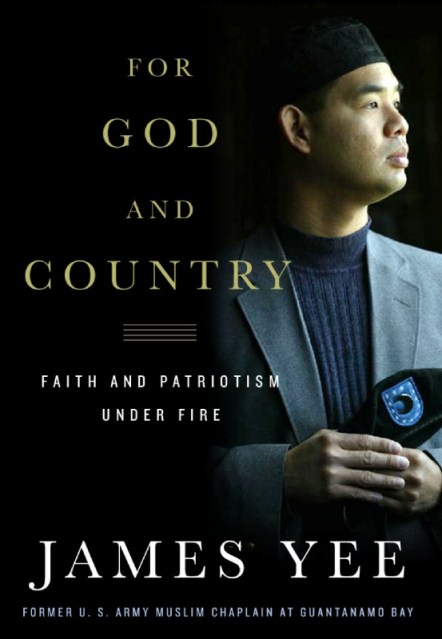

For God and Country

Faith and Patriotism Under Fire

Contributors

By James Yee

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 11, 2005

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786749478

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 11, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In September 2003, after serving at Guantanamo for ten months in a role that gave him unrestricted access to the detainees — and after receiving numerous awards for his service there — Chaplain Yee was secretly arrested on his way to meet his wife and daughter for a routine two-week leave. He was locked away in a navy prison, subject to much of the same treatment that had been imposed on the Guantanamo detainees. Wrongfully accused of spying, and aiding the Taliban and Al Qaeda, Yee spent 76 excruciating days in solitary confinement and was threatened with the death penalty.

After the U.S. government determined it had made a grave mistake in its original allegations, it vindictively charged him with adultery and computer pornography. In the end all criminal charges were dropped and Chaplain Yee’s record wiped clean. But his reputation was tarnished, and what has been a promising military career was left in ruins.

Depicting a journey of faith and service, Chaplain Yee’s For God and Country is the story of a pioneering officer in the U.S. Army, who became a victim of the post-September 11 paranoia that gripped a starkly fearful nation. And it poses a fundamental question: If our country cannot be loyal to even the most patriotic Americans, can it remain loyal to itself?

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use