Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

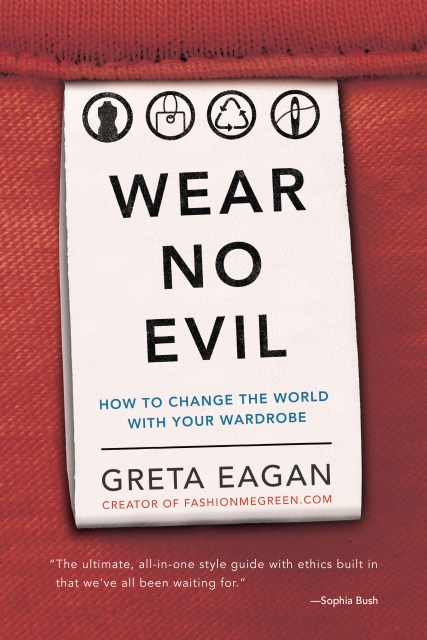

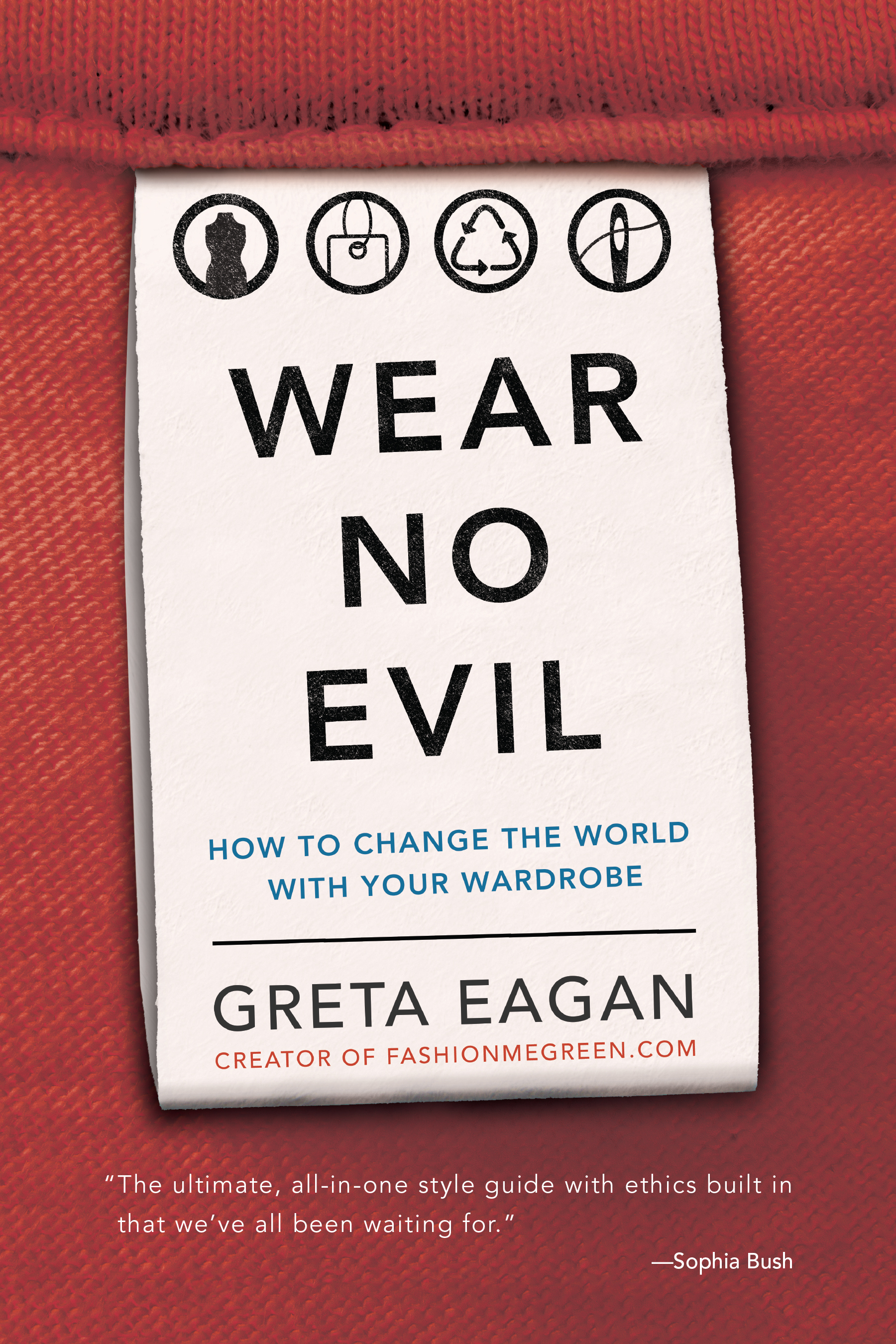

Wear No Evil

How to Change the World with Your Wardrobe

Contributors

By Greta Eagan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 11, 2014

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762451890

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 11, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Featuring the Integrity Index (a simplified way of identifying the ethics behind any piece of fashion) and an easy to use rating system, you’ll learn to shop anywhere while building your personal style and supporting your values- all without sacrifice. Fashion is the last frontier in the shift towards conscious living. Wear No Evil provides a roadmap founded in research and experience, coupled with real life style and everyday inspiration.

Part 1 presents the hard-hitting facts on why the fashion industry and our shopping habits need a reboot.

Part 2 moves you into a closet-cleansing exercise to assess your current wardrobe for eco-friendliness and how to shop green.

Part 3 showcases eco-fashion makeovers and a directory of natural beauty recommendations for face, body, hair, nails, and makeup.

Style and sustainability are not mutually exclusive. They can live in harmony. It’s time to restart the conversation around fashion — how it is produced, consumed, and discarded — to fit with the world we live in today. Pretty simple, right? It will be, once you’ve read this book.

Wear No Evil gives new meaning — and the best answers — to an age-old question: “What should I wear today?”

-

“The book holds a wealth of information that's useful both environmentally and personally, and Eagan's plea for a “reboot” of how people shop and clothe themselves is a timely entreaty for change.”

–Publishers' Weekly

The ultimate, all-in-one style guide with ethics built in that we've all been waiting for."

–Sophia Bush

"Rare is the book that speaks to your values while also providing a framework for realizing them in day to day actions. Wear No Evil does both in inspiring fashion. A must read for all who wear clothes."

—Ben Goldhirsh, Co-Founder GOOD Magazine

“The more we uncover what lies behind the fashion industry and the clothes we wear, the more we realize the power we have, as fashion lovers, to change it for good. Wear No Evil is a great guide on how to transform the fashion industry, one wardrobe at a time".”

—Livia Firth, founder of Eco

"I love this book! Finally an approachable, practical, DO-ABLE how-to on going green with your wardrobe without sacrificing an iota of style!"

—Alysia Reiner, Actress (Orange is the New Black)