By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

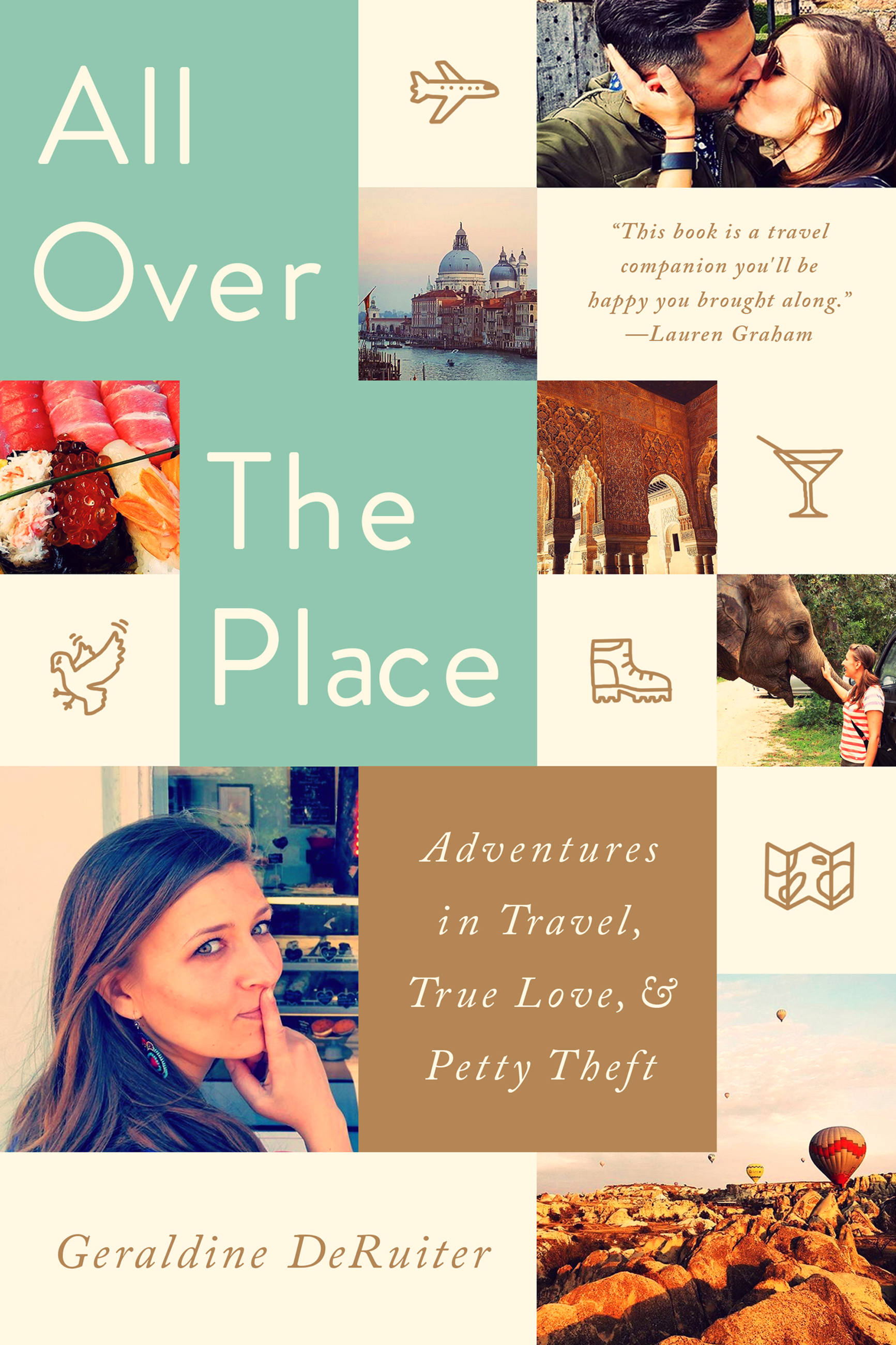

All Over the Place

Adventures in Travel, True Love, and Petty Theft

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610397643

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Geraldine DeRuiter is the latter. But she won’t let that stop her.

Hilarious, irreverent, and heartfelt, All Over the Place chronicles the years Geraldine spent traveling the world after getting laid off from a job she loved. Those years taught her a great number of things, though the ability to read a map was not one of them. She has only a vague idea of where Russia is, but she now understands her Russian father better than ever before. She learned that what she thought was her mother’s functional insanity was actually an equally incurable condition called “being Italian.” She learned what it’s like to travel the world with someone you already know and love — how that person can help you make sense of things and make far-off places feel like home. She learned about unemployment and brain tumors, lost luggage and lost opportunities, and just getting lost in countless terminals and cabs and hotel lobbies across the globe. And she learned that sometimes you can find yourself exactly where you need to be — even if you aren’t quite sure where you are.

Genre:

-

"Geraldine DeRuiter's All Over the Place is a travel memoir of sorts, but I'd enjoy reading pretty much any topic she wanted to cover. Her voice is funny, witty and warm, and her stories sparkle. This book is a travel companion you'll be happy you brought along."Lauren Graham, star of Gilmore Girls and New York Times bestselling author of Talking as Fast as I Can

-

"I laughed so hard during the book's 'disclaimer' that I woke up my baby, and then actively ignored him to continue reading. Geraldine is at turns laugh-out-loud hilarious and grab-me-some-tissues tender, and all I could think of after reading this was 'can we take a trip together please?'"Nora McInerny Purmort, author of It's Okay to Laugh (Crying Is Cool Too)

-

"DeRuiter's funny, honest portrayal of life's small and large adventures will convince any hesitant would-be traveler that you don't need bravery or even an above average sense of direction to venture out into the world-all you need is a plane ticket and a sense of humor (and maybe a plunger)."Rachel Friedman, author of The Good Girl's Guide to Getting Lost

-

"All Over the Place is a hilarious, authentic travel guide through the most mysterious and wonderful territory of all: the human heart."Martha Brockenbrough, author of the award-winning novel The Game of Love and Death

-

"Getting laid off from a job she adored opened the door to the blogosphere for DeRuiter, as she explains this irreverent, yet warm-hearted memoir. Readers of her blog the Everywhereist will be familiar with the author's style of using her personality quirks and health issues as the foundation for her conversation with the reader and revelations on life. "I hail from a long, nervous line of hypochondriacs," DeRuiter explains. Being afraid of travel and lacking a sense of direction haven't hindered her but rather helped her explore the world. "So, if there is any advice I could dispense, it would be this: it's absolutely incredible the things you can learn from not having a clue about where you're going." Her intimate memoir chronicles her adventures during the seven years she spent crisscrossing the globe, learning to understand and accept quirky family members. The author delves into her relationship with a workaholic-but-loving husband and a serious health crisis. DeRuiter's memoir is a light-hearted look at travel and learning to live life to the fullest each day, even if you not quite sure where you are going."Publishers Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use