By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

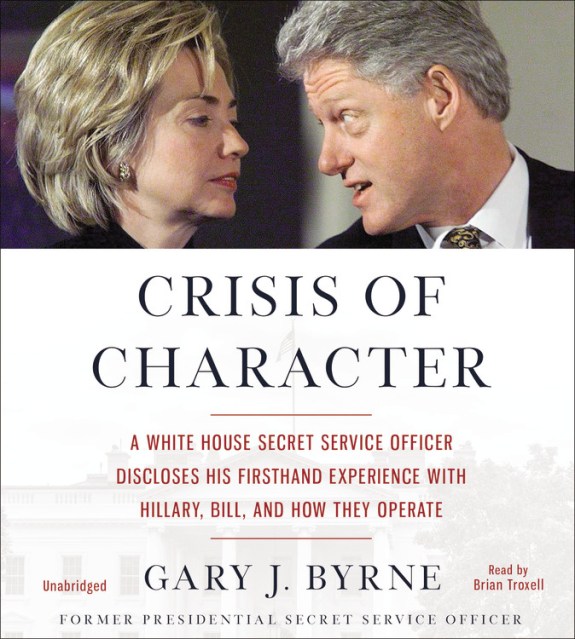

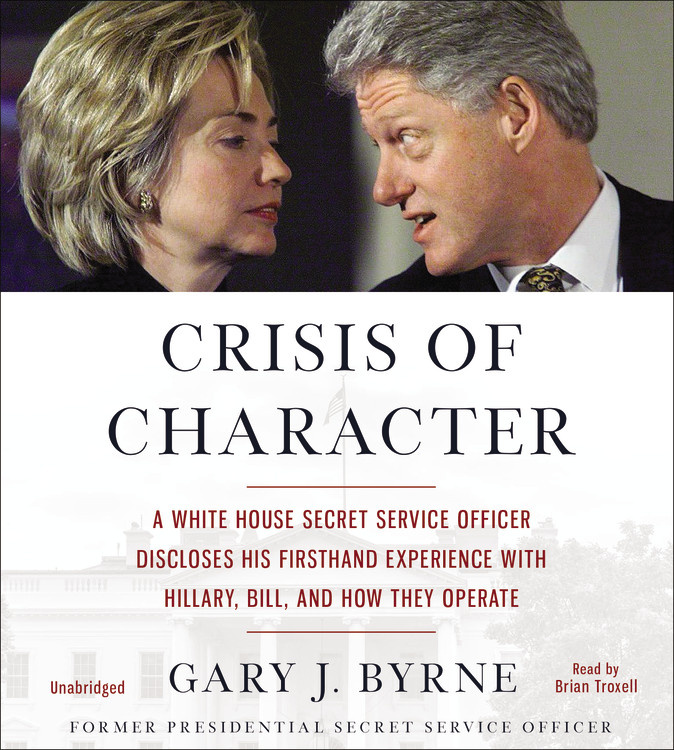

Crisis of Character

A White House Secret Service Officer Discloses His Firsthand Experience with Hillary, Bill, and How They Operate

Contributors

Read by Brian Troxell

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 28, 2016

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478966814

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 28, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

-

"I read it cover to cover!"Sean Hannity, Fox News Channel

-

"The book is worth reading to better understand the ways people who possess great power but lack character can abuse good public servants. Mr. Byrne's reporting on the flaws of the Federal Air Marshalls Service is also eye-opening - and scary."Fred J. Eckert, The Washington Times

-

"Hillary Clinton has a 'Jekyll and Hyde' personality that left White House staffers scared stiff of her explosive - and even physical - outbursts, an ex-Secret Service officer claims in a scathing new tell-all."New York Post

-

"Byrne reveals what he observed inside the White House while protecting the First Family in the 1990s."The Drudge Report

-

"[Crisis of Character] validates the public's growing distrust of Hillary's character. It reminds us of the Clintons' countless scandals and the deficits in their leadership. It is a message from someone who knew them personally, and it is a message we would do well to heed."Townhall.com

-

"Gary Byrne says he saw the pieces! In a box! Byrne is a former Secret Service officer who has written a tell-all book, "Crisis of Character," about the (horrible/embarrassing/appalling) things he purportedly witnessed during the Bill Clinton presidency."Gail Collins, the New York Times

-

"Byrne's What-the-Butler-Saw style account is particularly damning [...] so much of his testimony rings true based on what the world knows about goings-on at the Clinton White House. It is little wonder the Clinton camp has not only denounced the book, but has even reportedly persuaded most of the big TV news networks to deny Byrne airtime. [...] Byrne, now retired, counters that it is his 'patriotic duty' to ensure voters know the unvarnished truth about the Clintons."The Daily Mail

-

"Former Secret Service officer Gary Byrne offers a ground-zero look at the Lewinsky scandal - and other Bill Clinton misadventures that should have been national scandals - in his new book Crisis of Character. [...] As Bannon pointed out, the deterioration of Secret Service standards has arguably continued to the present day - one of two scandals presaged by the Nineties events recounted in Byrne's book, with the other being Hillary Clinton's email server. [...] Even though top Clinton White House officials have confirmed Byrne was an honorable officer, the Clinton machine has been working to pressure television networks into ignoring the news and helping Hillary Clinton's campaign by not reporting on the details contained within Byrne's bombshell book."Breitbart.com

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use