By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

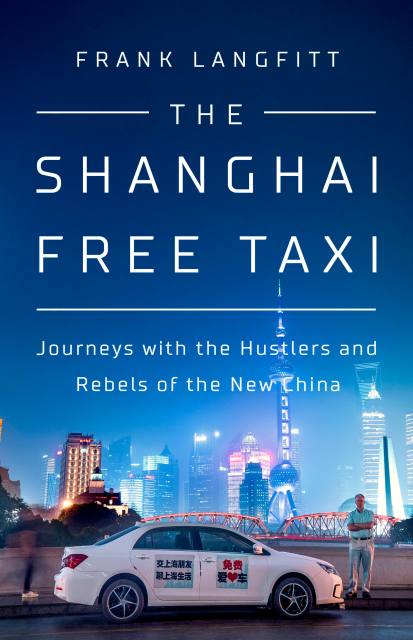

The Shanghai Free Taxi

Journeys with the Hustlers and Rebels of the New China

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 11, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610398152

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 11, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

China–America’s most important competitor–is at a turning point. With economic growth slowing, Chinese people face inequality and uncertainty as their leaders tighten control at home and project power abroad.

In this adventurous, original book, NPR correspondent Frank Langfitt describes how he created a free taxi service–offering rides in exchange for illuminating conversation–to go beyond the headlines and get to know a wide range of colorful, compelling characters representative of the new China. They include folks like “Beer,” a slippery salesman who tries to sell Langfitt a used car; Rocky, a farm boy turned Shanghai lawyer; and Chen, who runs an underground Christian church and moves his family to America in search of a better, freer life.

Blending unforgettable characters, evocative travel writing, and insightful political analysis, The Shanghai Free Taxi is a sharply observed and surprising book that will help readers make sense of the world’s other superpower at this extraordinary moment.

Genre:

-

"An engaging and dynamic narrative that offers readers an unusual perspective on modern China."-The Washington Post

-

"As Washington risks a new cold war with Beijing, Langfitt excels at humanising a country increasingly presented in purely oppositional terms . . . achieves a breadth rarely found in journalistic accounts of the country."-Financial Times

-

"The book is a master class on how to chronicle a changing country through the personal narratives of its citizens."-NPR

-

"Langfitt is an amiable, informed correspondent, and there is much to enjoy here for those looking to learn about modern China: for anyone in a Beijing-bound cab from the airport, forget about probing your cabbie for some home-spun authentic wisdom, and enjoy a few chapters of The Shanghai Free Taxi instead."Jonathan Chatwin, Asian Review of Books

-

"Lively, humorous, and touching, the book exposes the struggles of regular people in conflict with an authoritarian state. Without judgment, the author/driver allows his subjects to narrate their own adventures, leading to honest, raw, human stories."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Drawing on years of reporting, he provides context and a broader picture to anchor the narrative's kaleidoscope of characters, experiences, and opinions, making for a heartfelt, engaging, and informative read."Booklist

-

"does a great job of not romanticising the West . . . His comparisons of old and new China are informative and accurate . . . a comprehensive narrative of (the) New China."Cha

-

"Frank Langfitt devised an ingenious way to burrow into everyday Chinese life, and he came back with stories that are humane, candid, fast-paced, and compulsively readable. The Shanghai Free Taxi gives you the marrow of today's China in all its kindnesses and cruelties and wonders and absurdities."Evan Osnos, author of Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China, National Book Award winner

-

"An energetic and sympathetic reporter, Frank Langfitt follows individuals not only to the far ends of China, but also to the United States and Europe. Challenging to report but easy to read, this book reveals China's true transition: a profound search for identity in the world at large."Peter Hessler, New York Times-bestselling author of Country Driving, Oracle Bones, and River Town

-

"Frank Langfitt's stint as a taxi driver collecting tales of modern China has created a rollicking, delightful read. Enchanting."Mei Fong, author of One Child, and Pulitzer Prize winner

-

"A delightful, poignant, and revealing book. Langfitt got to see inside the lives of Chinese families of all backgrounds and social classes, and from many parts of the country. The result is a vivid look at the contradictory dreams, achievements, heartbreaks, and possibilities of modern China."James Fallows, author of Our Towns and China Airborne

-

"The Shanghai Free Taxi presents a unique, kaleidoscopic view of Chinese society. Characters in this book open up, talking freely and truthfully in a way unimaginable elsewhere under the oppressive regime. It is a must read for anyone trying to gain rare and insightful glimpses into that complicated country."Qiu Xiaolong, author of Shanghai Redemption and nine other Inspector Chen novels

-

"Frank Langfitt writes with the streetwise eye of a cabbie and the analytical mind of a foreign correspondent. This is today's China as it gossips; gripes and moans; strives; struggles; and overcomes."Paul French, author of City of Devils and Midnight in Peking

-

"A cleverly conceived, well executed book by an engaging and empathetic storyteller. Langfitt offers up an appealing mix of humorous and poignant tales featuring individuals from different backgrounds who share just one common trait: all are struggling to find their places in and make sense of an era when their city, their country and the world at large have been undergoing complex and often confounding transformations."Jeffrey Wasserstrom, coauthor of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know

-

"By creating a free taxi and offering free rides, veteran NPR reporter Frank Langfitt takes us on a journey across China and into the soul of today's Chinese civilization. We learn how a wide cross section of Chinese people live and think as the author provides an up-close view of their fears and aspirations and the forces that shape their lives in ways good and bad. I have lived in China for thirty years, and this book gave me new insights and brought me to places I have never been. Truly unique and compelling."James L. McGregor, chairman of APCO Worldwide's greater China region and author of No Ancient Wisdom, No Followers and One Billion Customers

-

"A fascinating travelogue slash meditation on modern China . . . it is Langfitt's skill with the written word and his ability to establish ideas through vivid examples that sets his work apart."-That's Shanhai

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use