By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

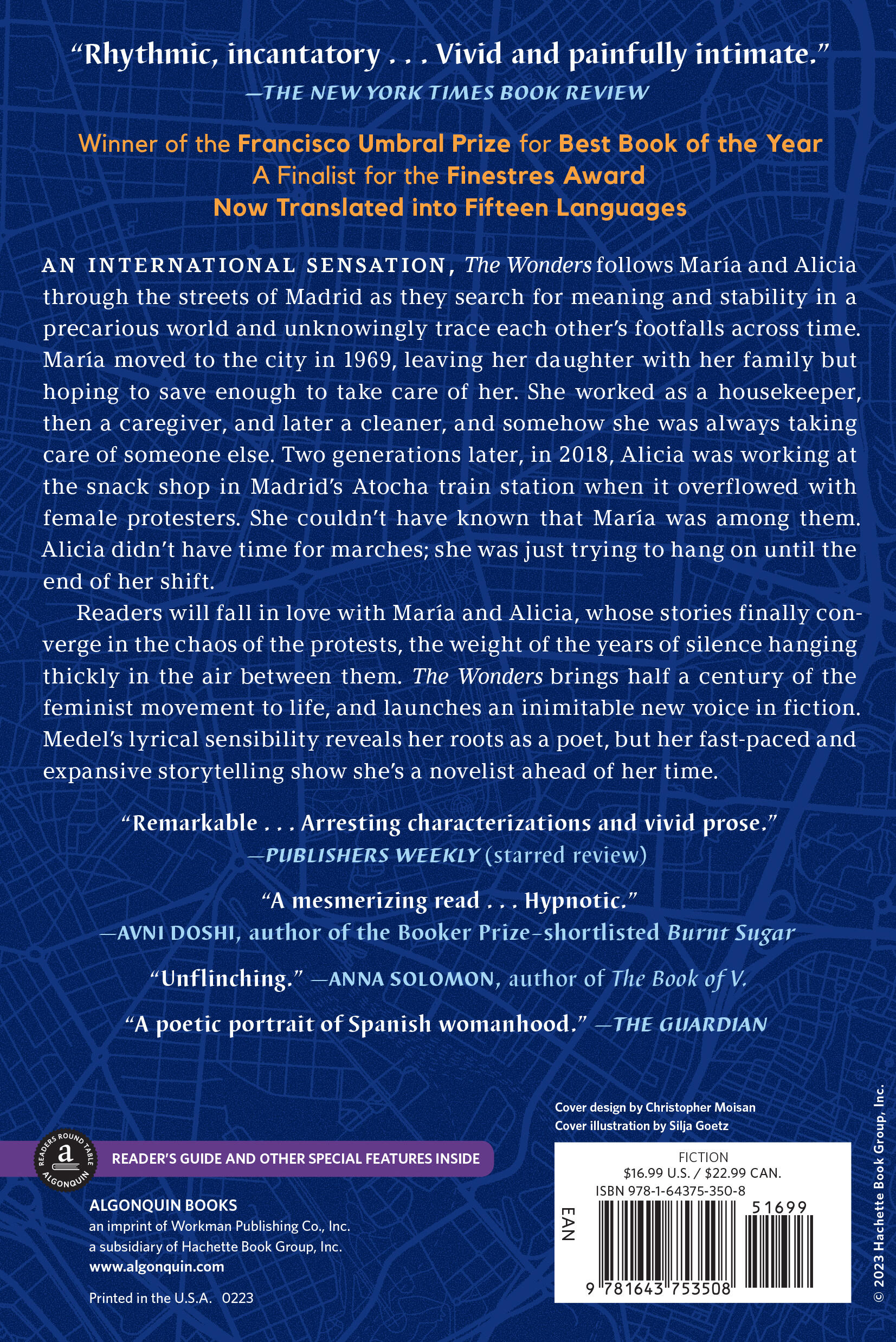

The Wonders

Contributors

By Elena Medel

Translated by Lizzie Davis

Translated by Thomas Bunstead

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2023

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643753508

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Winner of the Francisco Umbral Prize for Best Book of the Year

A Finalist for the Finestres Award

Now Translated into Fifteen Languages

An international sensation, The Wonders follows María and Alicia through the streets of Madrid as they search for meaning and stability in a precarious world and unknowingly trace each other’s footfalls across time. María moved to the city in 1969, leaving her daughter with her family but hoping to save enough to take care of her. She worked as a housekeeper, then a caregiver, and later a cleaner, and somehow she was always taking care of someone else. Two generations later, in 2018, Alicia was working at the snack shop in Madrid’s Atocha train station when it overflowed with female protesters. She couldn’t have known that María was among them. Alicia didn’t have time for marches; she was just trying to hang on until the end of her shift.

Readers will fall in love with María and Alicia, whose stories finally converge in the chaos of the protests, the weight of the years of silence hanging thickly in the air between them. The Wonders brings half a century of the feminist movement to life, and launches an inimitable new voice in fiction. Medel’s lyrical sensibility reveals her roots as a poet, but her fast-paced and expansive storytelling show she’s a novelist ahead of her time.

-

“Medel’s poetic sensibility is evident in rhythmic, incantatory prose, yet she also looks at the world through a good novelist’s magnifying glass . . . Medel makes room for her characters to grow into their power as women, a power they discover does not in fact lie in money.”El País

I>The New York Times Book Review

“The Wonders is a poet’s novel, delicate but strong, impressing its images firmly on the imagination.”

—Hilary Mantel, author of Wolf Hall

“A poetic portrait of Spanish womanhood . . . The lives of two working-class women are interleaved in a bold debut novel with flashes of beauty.”

I>The Guardian

“Medel captures the plight of working women who are limited by class and gender dynamics . . . Small acts of protest add up to each woman's larger fight for freedom from the confines of men, money and everlasting grief . . . Though they have made mistakes and been lonely, they have survived. And that triumph they claim for themselves.”

—NPR

“The Wonders is the long-awaited novel debut by one of the best poets of the new Spanish generation. The Wonders is a novel about money—a novel about how the money we don't have defines us. It is also a novel about care, responsibilities, and expectations; about the precariousness that does not respond to the crisis but to the class, and about who will tell the stories that define our origins and our past.”

I>Conde Nast Traveler

“A captivating novel . . . Medel’s poetic voice shines.”

—Karla Strand, Ms. magazine

“A mesmerizing read. Medel’s prose is hypnotic--it’s hard to believe this is her first novel. I was completely engrossed in this story, in the shadow each generation casts on the one that comes after it, in the tension between caring for oneself and caring for others.”

B>Avni Doshi, author of the Booker Prize finalist Burnt Sugar

“A remarkable English-language debut . . . Arresting characterizations and vivid prose fuel Medel’s searing look at the impact gender, class, and financial hardships have on working-class Spanish women’s lives as the country is buffeted by wider cultural shifts. It adds up to a powerful story.”

B>Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Prizewinning Spanish poet Medel’s debut novel examines the lives of three generations of women in Madrid with an unsparing eye . . . The translation from Spanish of Medel’s unvarnished look at three constrained lives is unsentimental and direct.”

B>Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Medel's sensitive debut, charged with feminist insights but never losing sight of the particularities of its characters, weaves together the stories of two women whose deeper connection only becomes clear as the novel approaches its end . . . Spanish novelist Medel astutely examines the forces--political, economic, familial, and personal--that have shaped the two women's richly detailed lives. Though penned in by class and gender, often in ways they do not recognize, Maria and Alicia come across not as simple victims but as struggling survivors, still open to change.”

B>Booklist (starred review)

“I read The Wonders is one page-turning night. Yet to describe Elena Medel’s debut as gripping is to miss the point. An unflinching story about class, sex, family, and working women everywhere, this book achieves a rare combination of novelistic plotting and virtuosic interiority that left me rooting for Maria and Alicia as if I’d known them all my life."

/B>Anna Solomon, author of The Book of V.

“Vivid and mesmerizing. The translators knocked it out of the park and the prose just oozes off the page.”

—Adam Vitcavage, Debutiful

“A stylistic triumph . . . Reminiscent of Elena Ferrante and Virginia Woolf, The Wonders is a stunning debut about the intersection between poverty and womanhood.”

I>BookBrowse

“Dreamlike yet precise, internal yet expansive, The Wonders moves between generations of women with a clear-eyed empathy for their struggles to be free. Medel's characters are hungry, angry, imperfect, and completely alive.”

B>Adrienne Celt, author of Invitation to a Bonfire and End of the World House

“The Wonders brings to life several generations of working women: it’s a serene and impious novel that puts class, feminism, and the eternal complexity of family ties at the fore.”

B>Mariana Enriquez, author of Things We Lost in The Fire and the Booker Prize finalist The Dangers of Smoking in Bed

“Reminds you of the audacity of Virginia Woolf . . . One of Spain’s best poets has become one of its most important novelists.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use