By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

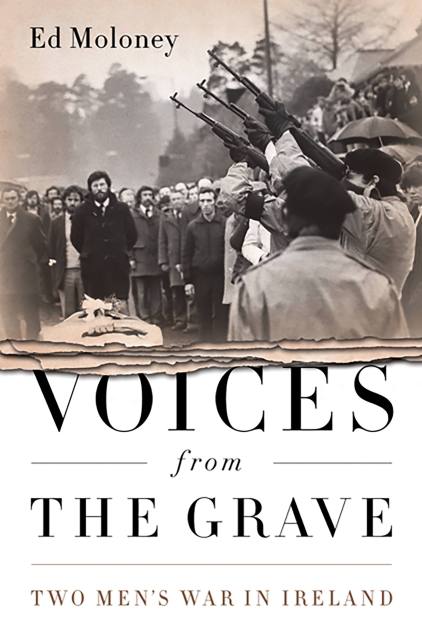

Voices from the Grave

Two Men's War in Ireland

Contributors

By Ed Moloney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2010

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489328

Price

$25.99Price

$33.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $33.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

After ‘the long war’ in Ireland came to an end, very few paramilitary leaders on either side spoke openly about their role in that bloody conflict, but in Voices from the Grave, two leading figures from opposing sides reveal their involvement in bombings, shootings and killings on one condition: that their stories were kept secret until after their deaths. In extensive interviews given to researchers from Boston College, Brendan Hughes and David Ervine spoke with astonishing openness about their turbulent, violent lives.

Hughes was a legend in the Republican movement. An ‘operator’, a gun-runner and mastermind of some of the most savage IRA violence of the Troubles, he was a friend and close ally of Gerry Adams and was by his side during the most brutal years of the conflict.

David Ervine was the most substantial political figure to emerge from the world of Loyalist paramilitaries. A former Ulster Volunteer Force bomber and confidante of its long-time leader Gusty Spence, Ervine helped steer Loyalism’s gunmen towards peace, persuading the UVF’s leaders to target IRA and Sinn Fein activists and push them down the road to a ceasefire.

Now their stories have been woven into a vivid narrative which provides compelling insight into a secret world and events long hidden from history.

Genre:

-

The first and more gripping half of this fascinating, important book by Ed Moloney recreates Hughes's IRA career through his later reflections on it.Irish Times

-

This candid analysis of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, as seen through the eyes of two men of violence, is full of revelations ... The memories of both men are vivid, gossipy and informed by an intense moral passion.Daily Express

-

[A] moving new book, which traces the conflict from [Hughes' and Erskine's] often diametrically opposed perspectives ... Moloney's book expertly interweaves the two men's recollections with a detailed narrative of the conflict.Telegraph

-

How do you document the history of a conflict in which illegal organisations are among the central players? Voices from the Grave, by the veteran Northern Ireland correspondent Ed Moloney, is an intriguing attempt to answer that question.Open Democracy

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use