By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

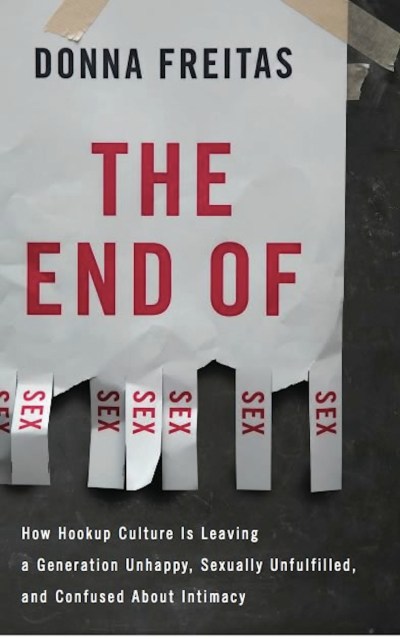

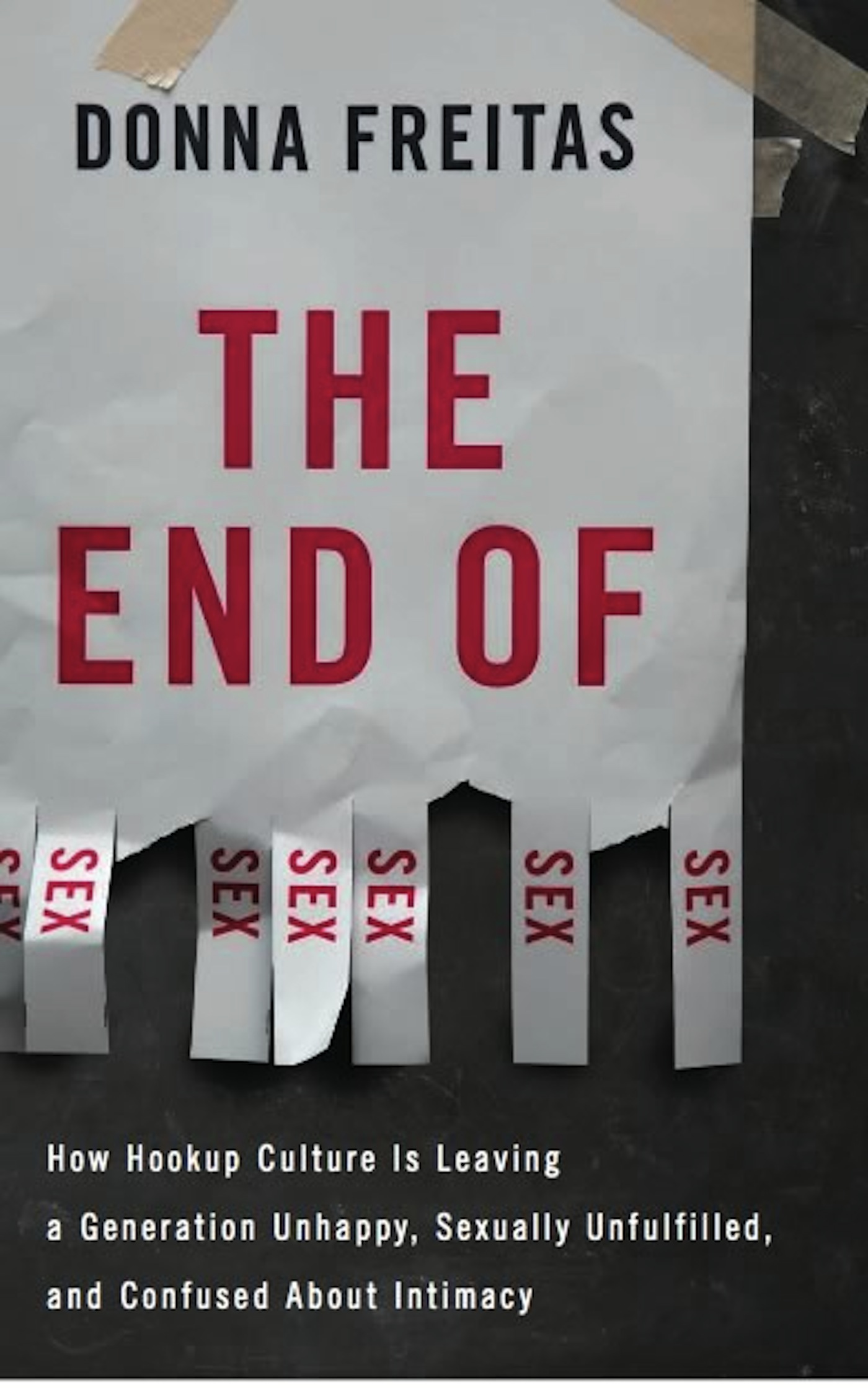

The End of Sex

How Hookup Culture is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Intimacy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2013

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465037834

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.99 $29.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In The End of Sex, Donna Freitas draws on her own extensive research to reveal what young men and women really want when it comes to sex and romance. Surveying thousands of college students and conducting extensive one-on-one interviews at religious, secular public, and secular private schools, Freitas discovered that many students — men and women alike — are deeply unhappy with hookup culture. Meaningless hookups have led them to associate sexuality with ambivalence, boredom, isolation, and loneliness, yet they tend to accept hooking up as an unavoidable part of college life. Freitas argues that, until students realize that there are many avenues that lead to sex and long-term relationships, the vast majority will continue to miss out on the romance, intimacy, and satisfying sex they deserve.

An honest, sympathetic portrait of the challenges of young adulthood, The End of Sex will strike a chord with undergraduates, parents, and faculty members who feel that students deserve more than an endless cycle of boozy one night stands. Freitas offers a refreshing take on this charged topic — and a solution that depends not on premarital abstinence or unfettered sexuality, but rather a healthy path between the two.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use