Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

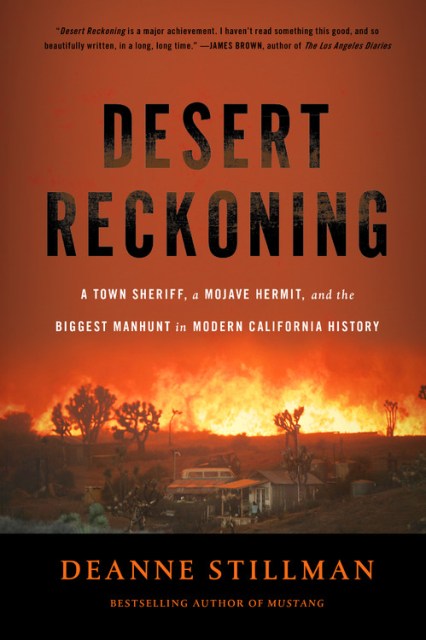

Desert Reckoning

A Town Sheriff, a Mojave Hermit, and the Biggest Manhunt in Modern California History

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568588636

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It is against the backdrop of these two competing visions of land and space that Donald Kueck – a desert hermit who loved animals and hated civilization – took his last stand, gunning down beloved deputy sheriff Steven Sorensen when he approached his trailer at high noon on a scorching summer day. As the sound of rifle fire echoed across the Mojave, Kueck took off into the desert he knew so well, kicking off the biggest manhunt in modern California history until he was finally killed in a Wagnerian firestorm under a full moon as nuns at a nearby convent watched and prayed.

This manhunt was the subject of a widely praised article by Deanne Stillman, first published in Rolling Stone, a finalist for a PEN Center USA journalism award, and included in the anthology Best American Crime Writing 2006. In Desert Reckoning she continues her desert beat and uses Kueck’s story as a point of departure to further explore our relationship to place and the wars that are playing out on our homeland. In addition, Stillman also delves into the hidden history of Los Angeles County, and traces the paths of two men on a collision course that could only end in the modern Wild West. Why did a brilliant, self-taught rocket scientist who just wanted to be left alone go off the rails when a cop showed up? What role did the California prison system play in this drama? What happens to people when the American dream is stripped away? And what is it like for the men who are sworn to protect and serve?

Genre:

-

“Desert Reckoning is a compelling literary work.”

David Steinberg, Albuquerque Journal

“Desert Reckoning is an evocative, richly textured narrative that places the reader squarely amid the ranchers, outlaw bikers, and dropouts who eke out an existence in the unforgiving heat and isolation of the Mojave Desert….Desert Reckoning is written in lovely lyrical prose. It renders beautifully the lives of the lost and marginalized souls who take refuge in the desert.”

Joseph Barbato, Red Weather Review

“[C]ritically acclaimed writer Deanne Stillman weaves an eloquent elegy of strange and twisted characters….A talented writer of literary nonfiction, Stillman writes beautifully about the Mojave, and once again makes it a character in the story.”

Colleen O'Connor, Denver Post

“This a real life desert noir written in prose as taut as Raymond Chandler….Stillman's book reads like a thriller.”

Jeffrey St. Clair, Counterpunch

“Stillman has a novelist's flair for colorful explanation.”

Rob Hardy, Commercial Dispatch

“A page turner.”

Kevin Roderick, LA Observed -

“Deanne Stillman does for the ‘lonely heart' of the desert behind Los Angeles what Raymond Chandler did for the shabby glamour of the city's garden suburbs. You can hear dreams being broken in every sentence of Desert Reckoning. In Stillman's propulsive, often hallucinatory account, a brutal crime and its strange aftermath expose the terrors and beauties that still inhabit the empty places that lie at the end the city's freeways.”

D. J. Waldie, author of Notes from Los Angeles: Where We Are Now

“Desert Reckoning is a major achievement. Fusing truth with the insight of a talented novelist's imagination, Deanne Stillman has created a masterpiece of empathy and understanding for those so often least afforded it. Nothing here is simply rendered. Stillman's vision of society's outcasts, the lost souls who take their final stand in the badlands of California's deserts, demonstrates a remarkable sense of humanity and compassion. I haven't read something this good, and so beautifully written, in a long, long time."

James Brown, author of The Los Angeles Diaries, and This River -

“Deanne Stillman is the Raymond Chandler of the New West, a hell of a writer who leaves no cacti unturned, no long-dried gulch unexamined, and no abandoned settlement left be in her latest gritty, implausible-yet-too-real story. The tale told in Desert Reckoning will quickly join the same vein of Western anti-hero epics such as Willie Boy and Tiburcio Vasquez.”

Gustavo Arellano, author of Orange County and the syndicated column, ¡Ask a Mexican!

Norm Stamper, Seattle Chief of Police (retired) and author of Breaking Rank

“Deanne Stillman’s meticulously researched book takes us behind the scenes of real police work and into the hearts and minds of two men. In her spellbinding account of the murder and the massive manhunt, she leaves no doubt as to the consequences of how we raise our children, particularly our sons.”

Jo-Ann Mapson, author of Finding Casey and Solomon's Oak

“Deanne Stillman’s work is gritty and unflinching, yet filled with humanity.”

-

“It's all too rare these days that a book keeps me awake at night, racing through its pages yet not wanting it to end—but that's what happened with Desert Reckoning.”

Anneli Rufus, Stuck blog of Psychology Today

"Stillman...is the voice writing about the Mojave Desert, a place where serenity and violence wrestle for domination unto eternity."

Nancy Rommelmann, The Oregonian

“With a reporter's eye for detail, a novelist's sense of pace and no fear of inserting her own voice into the action, Deanne Stillman takes us through the history of Kueck's deranged anger and the massive effort to take him down….When the smoke clears, we are left only with Stillman's vivid images of cold violence in the hot wilderness of an American desert.”

Shelf Awareness

“Mysterious and terrifying.”

Susan Salter Reynolds,Los Angeles Magazine

“[V]ibrant….[Stillman] does an admirable job building a full portrait of this beleaguered landscape….The result is lyrical and intense….A dynamic synthesis of Western saga, true-crime thriller and California-based transformation narrative.”

Kirkus Reviews -

“Stillman explores, with exquisite detail, the broken families and failed strivings of her two protagonists….Stillman skillfully excavates the vividly drawn landscape to reveal the desert's mystical spirit and history of human striving….Through the lens of a griping true crime story, this beautifully written, humane book preserves the history of a remarkable and very American place and its people.”

Publishers Weekly

“Deanne Stillman's Desert Reckoning is a modern-day corrido, a protest ballad of lost lives and broken dreams set in the vast Mojave, one of California's most delicate and volatile regions, a too-often-forgotten landscape beyond the surf, the stars, and the palm trees. The rhythms, beats, and chords of Stillman's writing—brutal, haunting, and heartbreaking—bear witness to the lives of lonely hermits and desperate tweakers, outlaw bikers and tenacious cops, in prose that shimmers and aches so beautifully that it splits your soul and shakes loose your skin, leaving you speechless and yearning for more and more. With this book, Deanne Stillman proves once again why she is one of the most powerful chroniclers of the modern American West.”

Alex Espinoza, author of Still Water Saints -

“[The Mojave Desert] now has its own poet laureate in Deanne Stillman….[Desert Reckoning] is the most powerful and important writing about the place and its denizens since Mary Austin's classic The Land of Little Rain….The dark tale she returns with is one of aching heartbreak and haunting beauty. It is about the terror and beauty of the GreatAmerican Desert, and of the shadowy landscape of the human soul….This fiery-hot mosaic of the book sizzles from its opening pages. Its finely drawn characters and taut narrative emerge from the ancient deserts of our dreams and make real our fears. Deanne Stillman is a literary shaman who has conjured a violent and potent vision of our disturbing life and times—a vision without judgment, but filled with empathy and wonder. This is not natural history, nor is it true crime. It is something entirely new that Stillman has created from deep within the sun-blasted heart of the American dream.”

Jon Shumaker,Tucson Weekly

“Stillman is a great writer, and one of the few who fully capture the sparse culture [of] our California deserts….She has enormous sympathy for everyone involved, and yet never lapses into sentimentality or melodrama. The text rocks along like a good novel.”

Tom Lutz, LA Review of Books on KCRW -

Named "Southwest Book of the Year" by Pima County Public Library

Winner of the 2013 Spur Award for Best Western Nonfiction Contemporary

Winner of the 2013 LA Press Club Award for best general nonfiction

"One of the greatest gifts of this book is how Deanne Stillman is able to open our hearts to people we might otherwise judge or dismiss...One can't help but be filled with gratitude and awe toward Deanne Stillman — her clear eye, the depth of her research, her brave and compassionate imagination. She takes us on a journey as full of desolation and grandeur as the desert itself."

Gayle Brandeis, Los Angeles Review of Books

"A must-read for the summer."

Rolling Stone

“Few writers capture the rhythm and brutality of the American Southwest quite like Deanne Stillman….[a] fascinating new book….Stillman writes with such clarity, insight, and exquisite detail, one feels the chap of the heat and inhospitality of the desert on each page. Simply put, this is crime reporting at its very best and by an author [who] is at the top of her game. Meticulously researched, beautifully written, Desert Reckoning is a true achievement and a modern masterpiece.”

Larry Cox, King Features Syndicate