Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

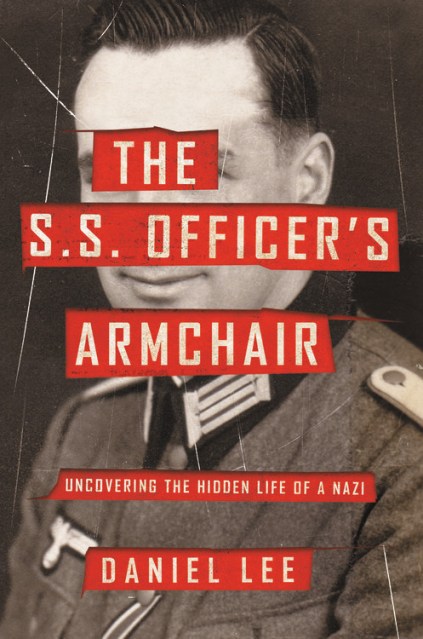

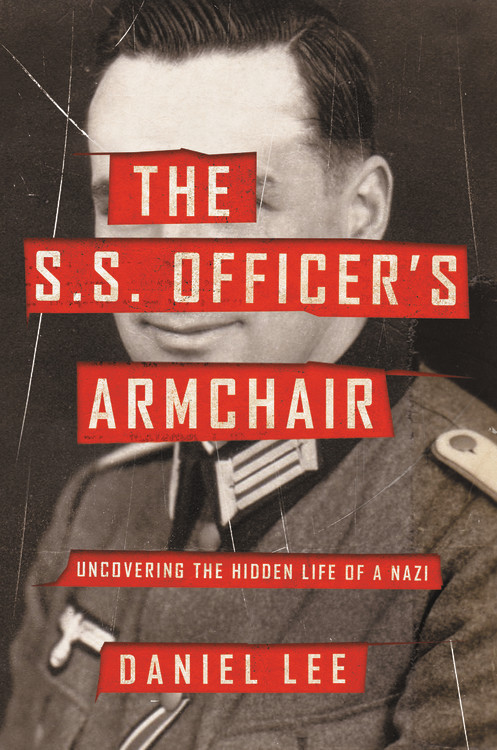

The S.S. Officer's Armchair

Uncovering the Hidden Life of a Nazi

Contributors

By Daniel Lee

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 16, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Based on documents discovered concealed within a simple chair for seventy years, this gripping investigation into the life of a single S.S. officer during World War Two encapsulates the tragic experience of a generation of Europeans

One night at a dinner party in Florence, historian Daniel Lee was told about a remarkable discovery. An upholsterer in Amsterdam had found a bundle of swastika-covered documents inside the cushion of an armchair he was repairing. They belonged to Dr. Robert Griesinger, a lawyer from Stuttgart, who joined the S.S. and worked at the Reich’s Ministry of Economics and Labor in Nazi-occupied Prague during the war. An expert in the history of the Holocaust, Lee was fascinated to know more about this man–and how his most precious documents ended up hidden inside a chair, hundreds of miles from Prague and Stuttgart.

In The S.S. Officer’s Armchair, Lee weaves detection with biography to tell an astonishing narrative of ambition and intimacy in the Third Reich. He uncovers Griesinger’s American back-story–his father was born in New Orleans and the family had ties to the plantations and music halls of nineteenth century Louisiana. As Lee follows the footsteps of a rank and file Nazi official seventy years later, and chronicles what became of him and his family at the war’s end, Griesinger’s role in Nazi crimes comes into focus. When Lee stumbles on an unforeseen connection between Griesinger and the murder of his own relatives in the Holocaust, he must grapple with potent questions about blame, manipulation, and responsibility.

The S.S. Officer’s Armchair is an enthralling detective story and a reconsideration of daily life in the Third Reich. It provides a window into the lives of Hitler’s millions of nameless followers and into the mechanisms through which ordinary people enacted history’s most extraordinary atrocity.

One night at a dinner party in Florence, historian Daniel Lee was told about a remarkable discovery. An upholsterer in Amsterdam had found a bundle of swastika-covered documents inside the cushion of an armchair he was repairing. They belonged to Dr. Robert Griesinger, a lawyer from Stuttgart, who joined the S.S. and worked at the Reich’s Ministry of Economics and Labor in Nazi-occupied Prague during the war. An expert in the history of the Holocaust, Lee was fascinated to know more about this man–and how his most precious documents ended up hidden inside a chair, hundreds of miles from Prague and Stuttgart.

In The S.S. Officer’s Armchair, Lee weaves detection with biography to tell an astonishing narrative of ambition and intimacy in the Third Reich. He uncovers Griesinger’s American back-story–his father was born in New Orleans and the family had ties to the plantations and music halls of nineteenth century Louisiana. As Lee follows the footsteps of a rank and file Nazi official seventy years later, and chronicles what became of him and his family at the war’s end, Griesinger’s role in Nazi crimes comes into focus. When Lee stumbles on an unforeseen connection between Griesinger and the murder of his own relatives in the Holocaust, he must grapple with potent questions about blame, manipulation, and responsibility.

The S.S. Officer’s Armchair is an enthralling detective story and a reconsideration of daily life in the Third Reich. It provides a window into the lives of Hitler’s millions of nameless followers and into the mechanisms through which ordinary people enacted history’s most extraordinary atrocity.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 16, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316509091

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use