Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

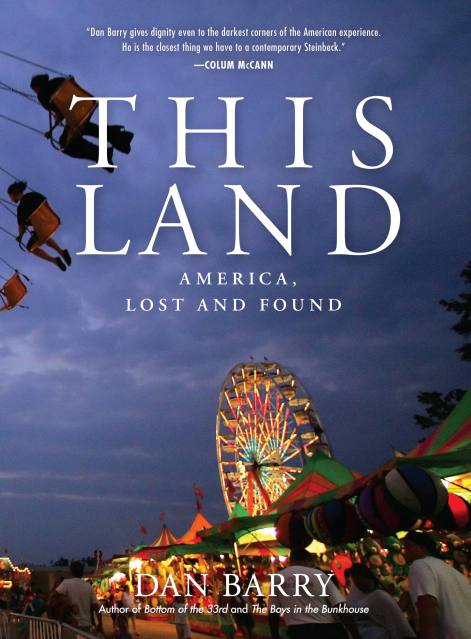

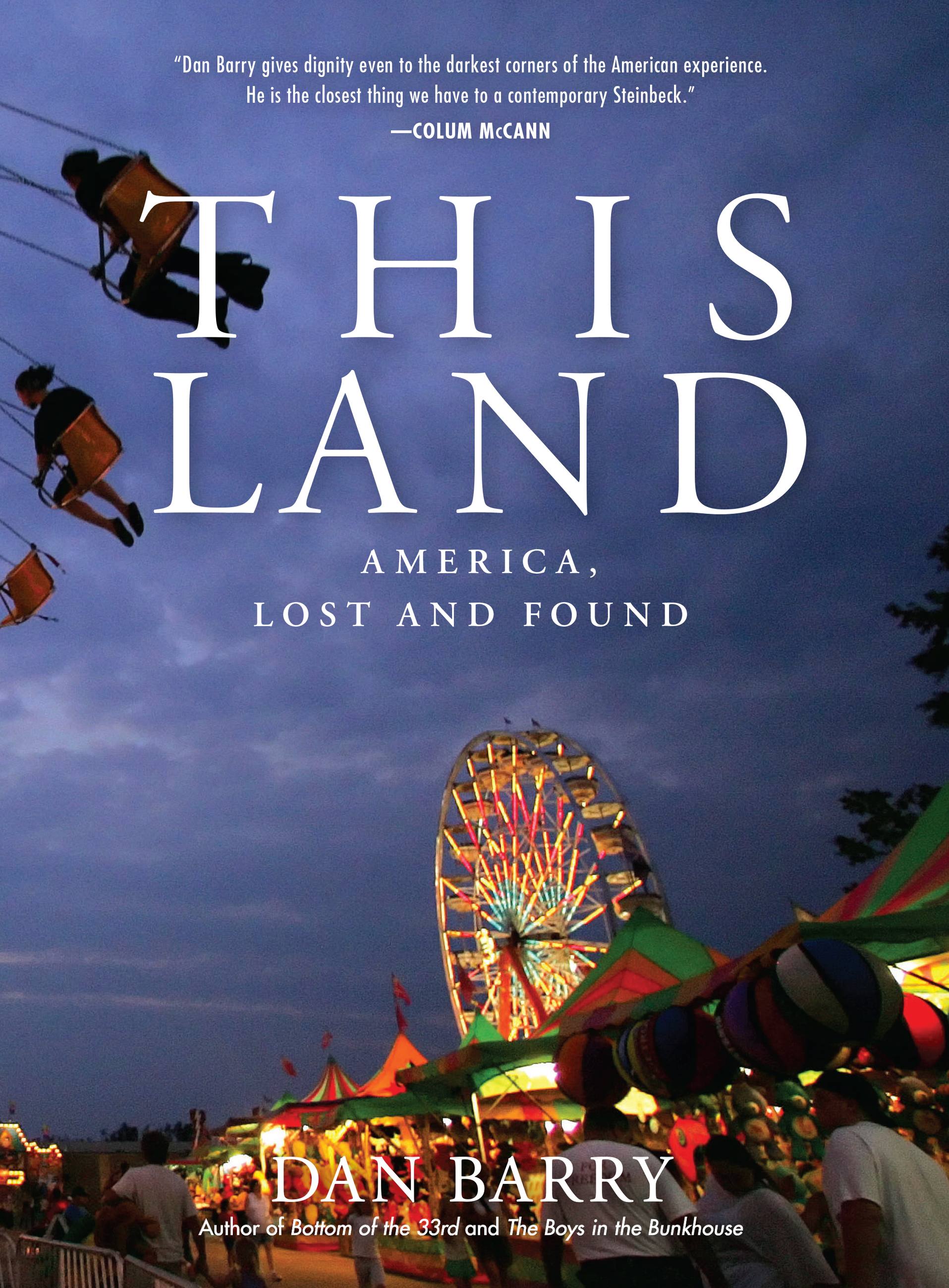

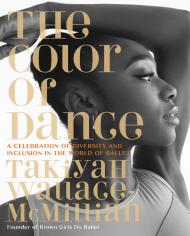

This Land

America, Lost and Found

Contributors

By Dan Barry

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.99 $38.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A landmark collection by New York Times journalist Dan Barry, selected from a decade of his distinctive “This Land” columns and presenting a powerful but rarely seen portrait of America.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina and on the eve of a national recession, New York Times writer Dan Barry launched a column about America: not the one populated only by cable-news pundits, but the America defined and redefined by those who clean the hotel rooms, tend the beet fields, endure disasters both natural and manmade. As the name of the president changed from Bush to Obama to Trump, Barry was crisscrossing the country, filing deeply moving stories from the tiniest dot on the American map to the city that calls itself the Capital of the World.

Complemented by the select images of award-winning Times photographers, these narrative and visual snapshots of American life create a majestic tapestry of our shared experience, capturing how our nation is at once flawed and exceptional, paralyzed and ascendant, as cruel and violent as it can be gentle and benevolent.

Genre:

-

"Story to story, this collection of reportage from Dan Barry for The New York Times might appear to be what it is - old journalism. And yet, what is actually here, a decade of stories about crumbling traditions, breaks in trust and flickers of grace, is the most comprehensive single-book portrait of the United States (circa 2007-2016) in a long time. The accumulated power of these pieces - angry, corny, inspiring, mournful and insane - takes on the shape of a salute to durable, keenly observed newspaper writing."The Chicago Tribune, 10 Best Books of 2018

-

"Dan Barry gives dignity even to the darkest corners of the American experience. He is the closest thing we have to a contemporary Steinbeck."Colum McCann

-

"Dan Barry is an American treasure, and This Land is a beautifully conceived, essential book on American lives and places. His understanding and love of the American experience-small towns, fractured lives, beauty, suffering, and the physical landscape-is unparalleled. I'm grateful to him, and for him, for chronicling our lives, honoring our history and recognizing our connection to each other."Rosanne Cash

-

"This Land reminds us that the greatest strength of the American character is America's characters: men and women who are resilient, gracious, eccentric, world-weary, bright-eyed, funny, complex, tragic, surly and yes, even, kind. Dan Barry proves once again that in his intelligent company, attention paid is its own reward. He assures us, too, that eloquence, wit, and compassion - all the virtues we need now - have not been purged from American discourse and are alive and well in these pages."Alice McDermott

-

"There is something incrementally, and in the end almost infinitely heartbreaking and transformational about Dan Barry's haunting anthology... With a Dickensian breadth of curiosity and compassion, Barry has been determined to shadow and record a decade in the quotidian flow of national life-events that are all the more indelible, mysterious and uncanny for their specificity."Ric Burns

-

"A fine collection of Barry's smooth-as-silk and keenly observed columns for the New York Times. He travels to post-Katrina New Orleans, witnesses an execution in Tennessee, talks with the minister who befriended serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. Barry finds beauty in the tragic, the bizarre, the overlooked."The Star Tribune

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316415484

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use