By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

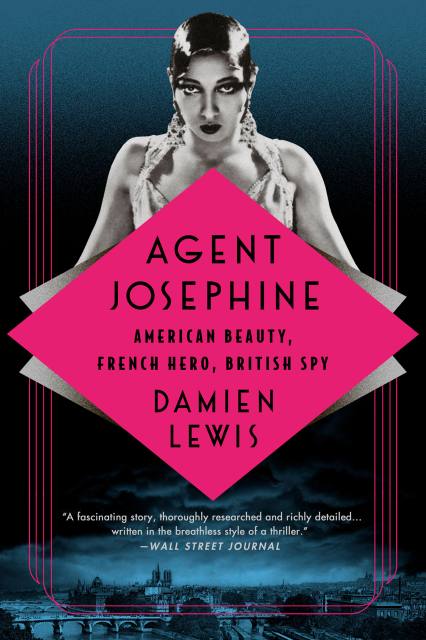

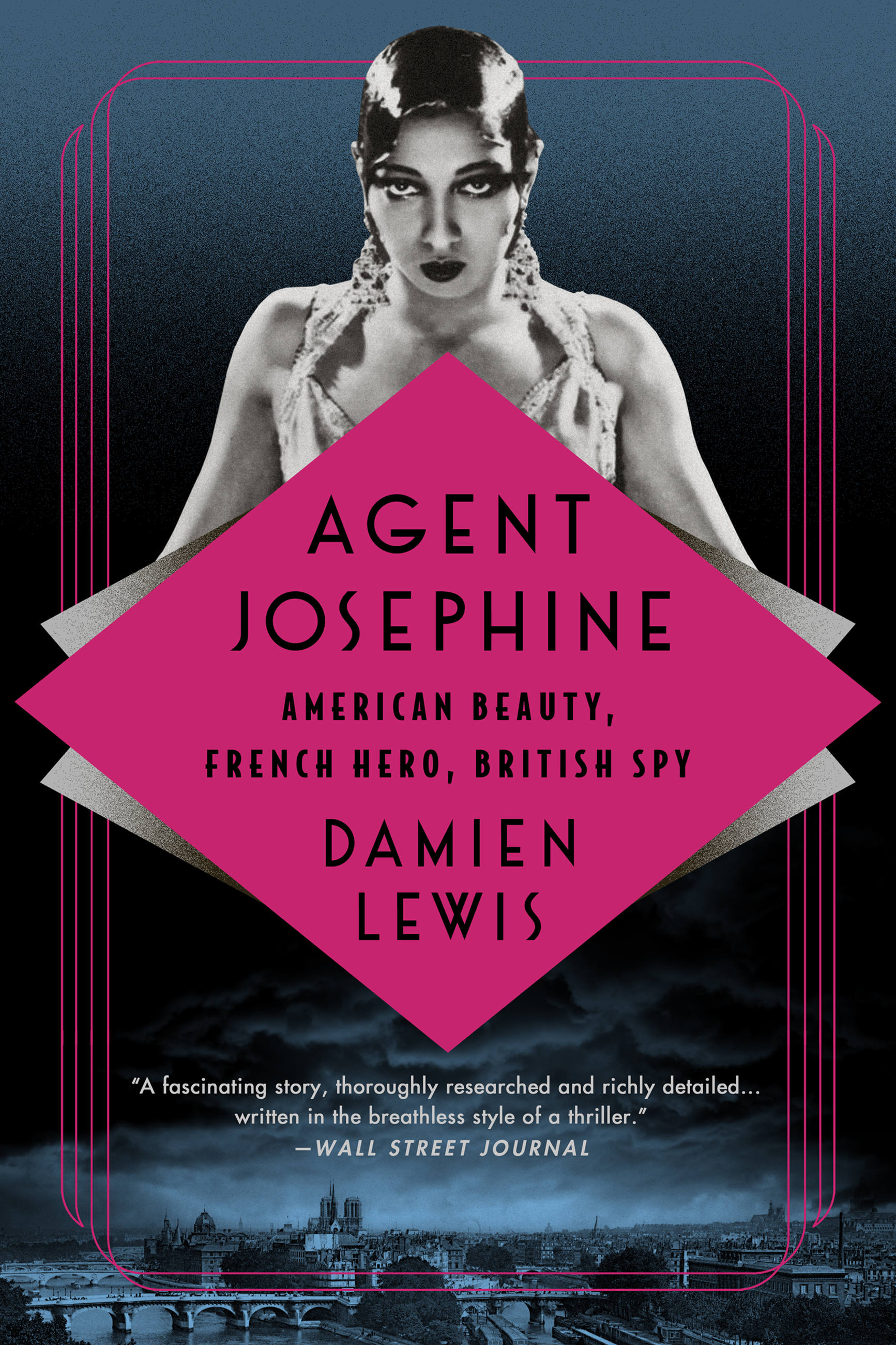

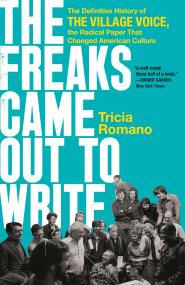

Agent Josephine

American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy

Contributors

By Damien Lewis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 12, 2022

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541700680

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 12, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Four hundred pages of bravery and heroism that read like a spy novel you can’t put down.” —Vanity Fair

A Vanity Fair and The New Yorker Best Book of the Year

In Agent Josephine, bestselling author Damien Lewis uncovers the extraordinary story of Josephine Baker's transformation from Paris performer to dauntless spy. Throughout World War II, using her stardom as a cloak for her secret work, Baker undertook daring clandestine missions to fight the Nazis, stamping an indelible mark on history.

Drawing on a plethora of new material and rigorous research, including previously undisclosed letters and journals, Lewis upends the conventional story of the renowned performer, revealing why she fully deserves her unique place in the French Panthéon.

-

“Damien Lewis chronicles [Josephine Baker] with much fresh detail… What most beguiles us today is the sense that a proud revolutionary lurked beneath the winsome savage, the snowy smile. Spycraft wasn’t so much what Baker did as who she was.”The New Yorker

-

“Mr. Lewis is a prolific author of wartime histories and novels… Agent Josephine is a fascinating story, thoroughly researched and richly detailed… Written in the breathless style of a thriller.”Wall Street Journal

-

“Damien Lewis journeyed down the rabbit hole of arcane European archives to piece together the elusive tale of Josephine Baker’s French espionage service during World War II. The result, which evokes the sensuous glamour of Baker’s expatriate superstardom, is 400 pages of bravery and heroism that read like a spy novel you can’t put down.”Vanity Fair

-

“Entertaining… Mr Lewis has researched his story thoroughly over the course of a decade, and tells it like a fast-paced spy thriller.”The Economist

-

“Lewis writes with a flair for hard-boiled drama, sharing insights into the clandestine world of espionage and its nests of expert, aristocratic spymasters; hard-living, shrewd field agents; and debonair mafiosos with their hideous henchmen… Agent Josephine is a wonderful addition to the canon of World War II stories.”Shelf Awareness

-

“In the compelling Agent Josephine: American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy, Damien Lewis sheds light on the performer’s remarkable espionage work, demonstrating that Baker’s global fame often provided the perfect cover for her perilous clandestine activities.”Christian Science Monitor

-

“Lovers of glamor, history, and intrigue will love this biography of Josephine Baker."St. Louis Magazine

-

“Lewis provides a rollicking, energetic commentary on Baker’s adventures.”Booklist, *starred review*

-

“Fascinating and riveting. What a story! It has never been told properly, if ever, before now. I know Josephine would be very proud of how she is portrayed.”Jean-Pierre Reggiori, Josephine Baker’s dance partner

-

“Damien Lewis’s ten years of research into Josephine Baker’s world as an operative for the allies during WWII takes her story to new heights. Escaping from the legend of a scantily clad singer/dancer who entertained the world, wartime Agent Josephine shines as bright as a beacon, shimmering with defiance, fierce in loyalty to her adopted France, and fully engaged in the collection and passage of intelligence. The love story that serves as a backdrop to her exploits resonates profoundly.”Jonna Mendez, author of The Moscow Rules

-

“Astonishing. Exhilarating. Agent Josephine captures the indomitable spirit of Josephine Baker. Under the dark skies of WWII, Josephine stared down the German occupation of France to become a master spy, risking her life in service of the French Resistance and the British Secret Intelligence Services—all while expressing the depth and wholeness of her character as a loyal friend and captivating entertainer. Working beyond the limits of endurance, she inspired diplomats, statesmen, spies, Moroccan Berber chieftains and battalions of allied troops to fight the Nazis and their ideals. Josephine’s odyssey calls to the resilience and creative tenacity that hides within all of us and bursts forth in the souls of a chosen few in extreme circumstances. Gripping as a thriller and superbly written. Everyone should read it.”Scott Lenga, author of The Watchmakers

-

“An eye-opening, pulse-quickening, richly-written history (and if Hitchcock was around today, he would be jostling to make the film). Josephine Baker led a wartime double life of extraordinary jeopardy: in public, a hugely-loved world-famous stage star; in the shadows, a formidably courageous secret agent fighting Nazis for the resistance and for MI6. Lewis’s needle-sharp narrative—swooping from the valleys of France to the exquisite palaces of north Africa, patterned with nerve-tautening escapes, betrayals, romance and near-death encounters, amid vividly conjured landscapes—is jagged with suspense. Yet he also writes with great warmth and sensitivity, creating a powerfully moving portrait of a woman who fought prejudice and hate in all its forms.”Sinclair McKay, author of Dresden and Berlin

-

“Damien Lewis has devoted considerable time and diligent research to revealing the real Josephine Baker.”Book Reporter

-

“Rather than crafting a conventional biography, Lewis concentrates on the wartime years, creating a heroic portrait of the selfless, brave, somewhat reckless, pioneering, unswervingly patriotic spy for the Allies… A complex, entertaining story of intrigue and sangfroid involving a beloved, courageous hero.”Kirkus

-

“A thrilling espionage story.”Publishers Weekly, *starred review*

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use