Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

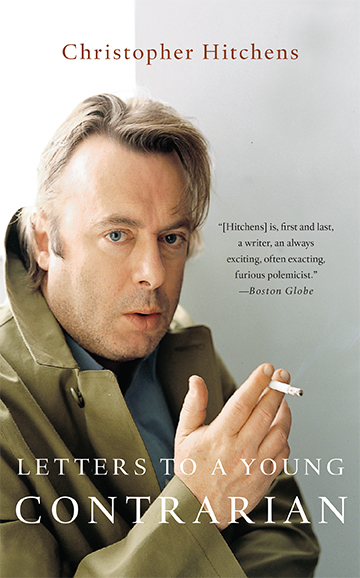

Letters to a Young Contrarian

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 13, 2005

- Page Count

- 160 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465030330

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 13, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Hitchens is, first and last, a writer, an always exciting, often exacting, furious polemicist.”―The Boston Globe

In Letters to a Young Contrarian, bestselling author and world-class provocateur Christopher Hitchens inspires the radicals, gadflies, mavericks, rebels, and angry young (wo)men of tomorrow. Exploring the entire range of “contrary positions”—from noble dissident to gratuitous nag—Hitchens introduces the next generation to the minds and the misfits who influenced him, invoking such mentors as Emile Zola, Rosa Parks, and George Orwell. As is his trademark, Hitchens pointedly pitches himself in contrast to stagnant attitudes across the ideological spectrum.

No other writer has matched Hitchens’s understanding of the importance of disagreement—to personal integrity, to informed discussion, to true progress, to democracy itself.

-

“[Hitchens] is, first and last, a writer, an always exciting, often exacting, furious polemicist.”The Boston Globe

-

“Hitchens exhibits precisely the combination of indignation and intellect that he recommends to others.”The New York Times Book Review

-

“Letters show Hitchens's best...He makes entertaining mincemeat of self-satisfied politicians and shreds received ideas and media-spun consensus with a fearlessness that is invaluable in our mealymouthed punditocracy.”The Village Voice

-

“Delicious...[Letters to a Young Contrarian] showcases Hitchens at his most savage and wise.”The Progressive

-

“Part revolutionist, part court jester, he is possessed of a wickedly effective prose style and a sense of moral purpose...True democracy could not exist without Christopher Hitchens and his ilk. May this book breed many more contrarians, young and old alike.”Time Out New York